In 2018, Umar Bebak from Pantha Chowk, Srinagar, entered into a joint venture with a Delhi-based company to manufacture and sell car cleaning products in Srinagar. He had taken the leap after a training programme at the Entrepreneur Development Institute in the city. Bebak borrowed Rs10 lakh from a bank to set up a manufacturing unit, rented a shop for Rs10,000 per month and paid a security deposit of Rs2 lakh.

He manufactured polishes for car bodies and cleaners for windscreens. Owing to good early demand, Bebak hired 15 salesmen and paid each Rs12,000 a month plus five per cent commission. Things were looking up till the internet blockade. The effect it had on Bebak’s business is an intriguing case study, because it was almost entirely brick-and-mortar, except for one aspect—he stayed in touch with his customers through emails and WhatsApp.

Post the internet blockade, phone calls did not have the same effect as the discussions online had, and sales plummeted. Six months on, Bebak, 24, has not been able to pay his staff and has also become a defaulter. He travelled to Delhi to mend things with his partner company, but his staff did not wait for his return. They quit, leaving his once thriving business in a shambles.

If small industries—people like Bebak—were blindsided by the internet blockade, the impact on Syed Ashfaq’s trading business was more straightforward. Ashfaq had quit a successful banking job to start a financial and data management service. After online trading came to a halt, Ashfaq persisted for three months, paying salaries without any work being done. But, he said he had to eventually lay off most of his staff. Ashfaq was also forced to move his office to more modest quarters. “I had planned an expansion. But, if the situation does not improve fast, I will have to look for a job,” he said.

On January 9, while hearing a plea against the internet blockade in Kashmir, the Supreme Court said access to the internet was part of freedom of speech and urged the Centre to review its decision. After the Supreme Court’s order, the state administration ordered the restoration of 2G internet for postpaid mobile users in a phased manner. The order, however, said the users can only access ‘white-listed’ sites. It also prevented access to social media sites and WhatsApp, invoking national security. The order said that 400 internet kiosks will be set up in Kashmir in addition to 834 internet terminals in government departments for the use of students, and traders and businessmen for filing GSTs.

Interestingly, landlines and broadband had been restored in Jammu a few weeks after the blockade. A fibre cable internet service launched by the Reliance Group also began operations in Jammu days after the abrogation of Article 370. But, the restoration of mobile internet in Kashmir has proven to be a sham, as abysmal connectivity makes accessing even white-listed sites impossible. Many people suspect the announcement regarding mobile internet was done only to create an impression of having complied with the Supreme Court order.

Houseboat owner Tariq Patloo said the denial of unrestricted internet access was likely to hamper the revival of tourism in Kashmir. “The internet was a handy medium for us to connect with tour operators and potential tourists outside Kashmir but now we have been deprived of that,” said Patloo. He said the internet facility set up by the government for tour operators was time-consuming and cumbersome. Patloo added that houseboat owners and hoteliers had suffered huge losses after a government advisory urged tourists to leave Kashmir two days before the abrogation of Article 370. It was not only the tourists who fled, he said, thousands cancelled their bookings, too.

The J&K tourism department initiated promotional programmes like ‘Back to Valley’ and roped in tour operators in Maharashtra and Gujarat to lure tourists to Kashmir. It also restored internet at tourist destinations in Gulmarg, Pahalgam and Sonmarg, but the footfalls did not increase significantly. According to Siraj Ahmed, hotelier and member of the Kashmir Economic Alliance, 80,000 tourists visited Kashmir in December 2018 for the winter festivities at Gulmarg. “Only 10 per cent of that number were present in Gulmarg in December 2019,’’ he said.

One of the biggest casualties of the blockade in Kashmir are the students, especially those who had to submit their forms online for the National Eligibility and Entrance Test. A heavy rush at government-run facilities for students forced many to go to Jammu, 300km from Srinagar, in December and January to submit their forms online. “In Jammu, it took only 10 minutes to download and five minutes to submit the [form for] NEET,” said Junaid, a student, who only revealed his first name. “Some girls were accompanied by their parents.”

The government has said it will restore broadband after users sign a bond listing six conditions. The conditions are denial of access to social media, virtual private networks and WiFi, denial of permission to upload encrypted files containing videos or photos, disabling USB ports, providing complete access as and when required by the security forces, denial of access to other devices through a computer and users taking responsibility for “any kind of breach or misuse of the internet”.

Similar conditions are in place for the government departments and hospitals. There are at least 20,000 landlines in use with private entities and people in Kashmir with broadband facility. According to sources, less than a 100 have agreed to sign the bond. The additional 400 kiosks ordered by the state have not been opened as the BSNL is struggling to instal firewalls.

According to a recent study by Delhi-based think-tank Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, the frequent internet disruptions have cost Kashmir’s economy Rs4,000 crore in the last six years. The study—The Anatomy of An Internet Blackout: Measuring the Economic Impact of Internet Shutdowns in India—highlighted that 34 shutdowns in 2017 alone caused a loss of Rs1,776 crore.

As per the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI), Kashmir has suffered losses worth Rs18,000 crore since August 2019. KCCI president Ashiq Hussain said the internet shutdown had added to the losses because of disruption in online shopping and other transactions. KCCI has estimated a loss of 09,191 crore in the services sector.

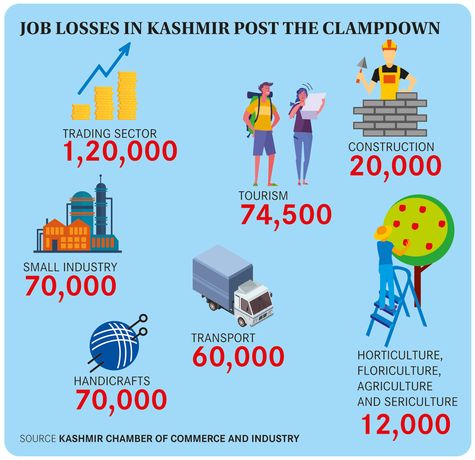

It also reported that at least 5,000 salesmen had not been paid salaries for the months of August, September and October, while 4.96 lakh people lost their jobs during the same period. The worst affected was the trading sector which saw 1.2 lakh jobs lost, followed by tourism which lost 74,500 jobs; the handicrafts sector and small industries lost 70,000 jobs each.