SUDHEER, an artist, lives in Baghban apartments in Delhi’s northern suburb of Rohini. The apartment compound was declared a containment zone and sealed off after a couple there contracted Covid-19 and died on May 4. The couple’s children were quarantined, but their test results were yet to come in.

A worried Sudheer downloaded Aarogya Setu (‘bridge to health’), a mobile app developed by the government to trace the spread of Covid-19 and alert users when and if their contacts test positive. He walked around the compound to test the app. But, even when Sudheer was in the area where the couple had died, Aarogya Setu displayed his status in happy, verdant letters—‘You are safe.’ “Many neighbours also got the same result,” he said. “What is the point of this app then?”

Sudheer’s story gives ammunition to supporters and critics of Aarogya Setu. The critics call it a tool for government surveillance, while supporters say the lack of complete coverage—less than 10 per cent of the population have the app—is what is limiting its efficacy.

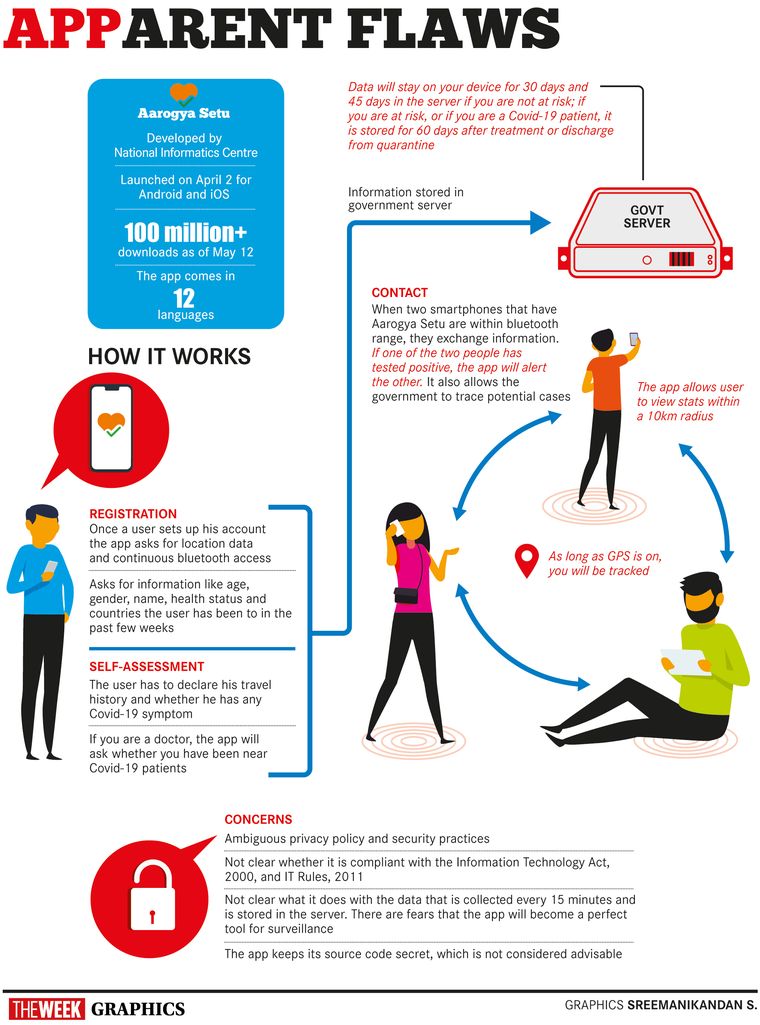

Since its launch on April 2, Aarogya Setu has been the government’s de facto tech tool against Covid-19. It has been downloaded more than 100 million times, but the news it has been making are not all good. “Aarogya Setu is a sophisticated surveillance system with no institutional oversight, raising serious data security and privacy concerns,” Congress leader Rahul Gandhi said on May 2, a day after the Union government made the app mandatory for people in containment zones and all government and private employees who were preparing to return to work after the lockdown was eased on May 4. “Technology can help keep us safe; but fear must not be leveraged to track citizens without their consent,” said Rahul.

A few days later, French ethical hacker Robert Baptiste, known as Elliot Alderson on social media, exposed what he said to be a series of security flaws in the app. This related to the number of times the app fetched the user’s location and an option that enabled users to change latitude, longitude and radius parameters to get statistics from different locations. “The privacy of 90 million Indians is at stake,” Baptiste said.

Ravi Shankar Prasad, Union minister of electronics and information technology, soon issued a denial. He said the app was “absolutely robust, safe and secure in terms of privacy protection and data security”. Authorities also released a six-page document detailing measures taken to protect privacy. It said every user was assigned a “random anonymous device ID” and that all info from users were deleted after a specific time. Location data was used only “in case you test positive, and only to map places visited in the past 14 days,” said the document.

The app is being aggressively promoted. Some states have made it mandatory for those who want to cross inter-state boundaries. Authorities in Noida have ordered that anyone found without the app in a public place be fined Rs1,000 or jailed for six months. The IT department in Tamil Nadu has asked all government employees to download the app, while Indian Railways has made it compulsory for passengers boarding special trains.

But the push is not backed by any ordinance or legislation. The order making Aarogya Setu mandatory was issued by an executive committee constituted under the provisions of the 2005 National Disaster Management Act, which gives the Union government sweeping powers and has been in force since the lockdown began. Justice B.N. Srikrishna, head of the committee that submitted a draft data protection bill last year, said the notifications making Aarogya Setu compulsory was “not backed by law”.

Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), a Delhi-based digital liberties NGO, has taken the matter to the parliamentary committee on IT, headed by Congress MP Shashi Tharoor. “[There is a] lack of clear basis or legislative framework for contact-tracing apps such as Aarogya Setu,” said Sidharth Deb, the IFF’s policy and parliamentary counsel. “[It is a] privacy minefield.”

According to him, Aarogya Setu “by design is aligned with the Chinese model of surveillance, which is in clear contravention of existing human rights benchmarks”. “India is the only democratic country in the world to make its app mandatory,” he said. (The UK’s House of Commons does not recommend the use of such apps, while countries like Australia have not made their use mandatory.)

Though Aarogya Setu was released by the National Informatics Centre, the government calls its development a “public-private” partnership. The IFF says the IT ministry’s response to queries regarding the app has been rather vague. “For example, the source code is not open-source and there is a lack of clarity on contract conditions and service rules for volunteers developing it,” said Deb.

NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant said Aarogya Setu was India’s attempt to leverage technology to fight Covid-19. “The app is privacy-first by design,” he said.

Kazim Rizvi, founder of the think tank The Dialogue and co-chair (public policy) of the Indian National Bar Association, said the use of Aarogya Setu was warranted. “Real-time response mechanisms require real-time insights,” he said. He pointed out that even the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in 2017 that made privacy a fundamental right had provisions to limit the scope of privacy. “The judgement lays down three key tests to reasonably restrict privacy—necessity, proportionality and legality.”

Rizvi’s suggestion: Bring an ordinance or legislation to “give a stronger legal footing to the use of this application”.

Deb, however, wants people to wake up to the dangers of letting it happen. “The public must understand that if they do not speak up, these systems can become permanent; they cannot be rolled back at a later juncture,” he said. “[We] must tell the government that it cannot have carte blanche access to our private lives.”