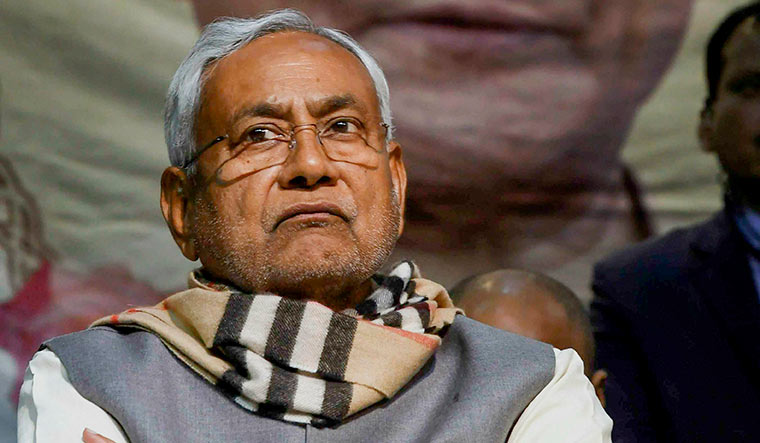

In his more than four-decade-old political career, the Bihar chief minister is facing his trickiest challenge ever—fighting the pandemic with a poor health infrastructure and managing the return of more than 30 lakh migrants, which will have a bearing on the assembly elections due in October-November. These apart, he has to tackle not only his opponents in the RJD-led Mahagatbandhan, but also his coalition partners in the BJP. He, however, seems unfazed.

Nitish enjoys the support of the BJP’s central leadership, which has declared him the chief ministerial candidate. But the opposition is a divided house. While the Rashtriya Janata Dal has picked Lalu Prasad’s son Tejashwi as the chief ministerial candidate, its allies—Jitan Ram Manjhi’s Hindustani Awam Morcha and Upendra Kushwaha’s Rashtriya Lok Samta Party are yet to voice their support.

But there has been criticism over Nitish’s handling of the Covid-19 crisis. Bihar ranks among the top ten states with the highest number of cases. The return of the migrants has stretched its inadequate health infrastructure. Migrants account for nearly two-third of the positive cases. The state has more than 12,000 block-level quarantine centres for migrants. Eight lakh of the 13.7 lakh migrants in these centres have been discharged. State Information and Public Relations Minister Neeraj Kumar told THE WEEK that a door-to-door screening of 1.87 crore households, covering 10.4 crore residents, was done. A similar screening would soon be carried out for migrants.

As of June 2, the state had tested 81,413 samples, of which 4,049 were positive. It is conducting only 62.4 tests per lakh of its population, while the recommendation is 200 tests per lakh. The positivity rate per 100 is 5—one in 20 samples test positive—which is close to the national average of 4.9. It means only the severely ill are being tested. A low positivity rate determines the policy on opening up of the economy. Kerala’s rate stands at 1.9. What has worked in Bihar's favour though is the low morbidity—30 deaths (as on June 8). This has eased pressure on the intensive care units in its three Covid-19 designated hospitals.

Nitish had repeatedly asked the Centre for more testing kits and monetary assistance. But he was seen as reluctant to welcome migrants home after the lockdown extension. Unlike his counterparts in other states, Nitish has been maintaining a low profile. Even the transfer of state health secretary Sanjay Kumar amid the crisis raised eyebrows. “We had never known this side of Nitish Kumar,” said Rajya Sabha MP Manoj Jha of the RJD. “He has been insensitive.”

Neeraj Kumar, however, said that the chief minister, like always, worked silently during a calamity. “It [fighting Covid-19] has been a challenge for a state with huge population and [poor] human index,” he said. “Had Bihar been like it was in 2005, would the migrants have returned? People trusted government facilities more than private ones. The state, which earlier had only three medical colleges, today has 15 in both government and private sector. Our handling has been much better.”

But the three heart-wrenching faces of the migrant crisis belong to the state: Rampukar Pandit, who was found sobbing by the roadside in Delhi as he could not travel to Begusarai to see his baby boy before he died; Arvina Khatoon, whose dead body lay on the Muzaffarpur railway platform even as her child tried to wake her up; and 15-year-old Jyoti Kumari who cycled over 1,200km from Gurugram to Darbhanga with her ailing father. Most migrants are dalits or belong to the extremely backward castes, and had migrated to cities to escape caste oppression. They would send money back home. But that social and financial security is now gone.

“We have a big crisis at hand. The total number of migrants who could have returned could be in the range of 40 lakh,” said Dr Shefali Roy, head of political science department at Patna University. “The one positive thing about the state is that because of prohibition, there are fewer complaints of domestic violence during lockdown unlike other areas. But as these migrants are returning, they may be bringing other infections like HIV. Lack of livelihood is likely to lead to increase in crimes. We are in a fix.” A state campaign to distribute condoms to migrants has been started.

Also, the state government said that it paid Rs1,000 each to migrants stranded in other states. Of the more than 29 lakh migrants who registered, more than 20 lakh were paid Rs204.05 crore by May 31. In addition, the state decided to reimburse train ticket fare and other travel expenses up to Rs1,000. For ration card holders, it is offering Rs1,000 as ‘Corona Sahayata’, and has paid an advance instalment on scholarships for students and provided assistance to farmers. In all, through five initiatives, the state has transferred more than Rs6,464.26 crore through direct benefit schemes. The state is now focusing on employing migrants based on their skills.

It is a given that the government’s handling of the crisis will have an impact on the poll results, but there is still uncertainty over when and how the elections will be held. “When we go to the polls, development and governance will be our main plank,” said Neeraj Kumar. “The timing of the polls will be decided by the Election Commission in consultation with the state. It is only then that the chief minister will give his views.”

There have been suggestions to hold the elections online, but the Election Commission has said that it will not be feasible to do so. Bihar's low mobile and internet penetration would be a challenge.

Nitish would prefer to hold the elections on schedule or continue as caretaker chief minister rather than have the state under Governor’s rule, as it may give better manoeuvrability to the BJP. Though both the BJP and Nitish’s Janata Dal (United) have been insisting that their alliance is intact, the saffron party’s local unit has been needling Nitish. Its other ally, the Chirag Paswan-led Lok Janshakti Party, may also ask for more seats this time.

The BJP, meanwhile, has begun its poll preparations. Its general secretary Bhupender Yadav, who is also in charge of the state, said, “Covid-19 will impact the campaign in a huge manner. But our party is present at the grassroots, which will engage with people.”

The party has already appointed a team of seven workers in each booth, based on the local caste composition. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi presented his ‘Mann Ki Baat’, the BJP tested its virtual campaign strategy by asking all the teams to listen in. “The conversation was tuned in at over 60,000 booths,” said BJP state chief Sanjay Jaiswal. “What this exercise also helped us in doing is to prepare programmes for the next three months at the booth level.” People have already been put in charge of each of the 243 seats.

On June 7, Home Minister Amit Shah held a virtual rally, first of the 75 such meetings to be organised by the BJP. Though he clarified that this was not an election rally, he said that Nitish Kumar-led NDA would return to power with two-third majority.

On the other hand, the RJD-led Grand Alliance is yet to sort out its differences. Unlike the last elections, when he spearheaded the campaign against the BJP, Lalu Prasad, who is jailed in a Ranchi prison, will be missing in action. And that will take the sting out of the opposition’s campaign. A friendly government in neighbouring Jharkhand has ensured that Lalu gets visitors, but he will have to go all out to cajole allies like Manjhi and Kushwaha, who prefer Loktantrik Janata Dal’s Sharad Yadav over Tejashwi for the chief minister’s post.

Tejashwi is trying to project himself as a counter to Nitish, by raking up the issues of migrants and unemployment. “Lakhs of migrant workers are suffering. We have not talked politics,” said Jha. “Even Tejashwi ji has said that only a brazenly insensitive party can think of organising a digital rally during such crisis.”

But the ruling alliance has an advantage: it will rely on the sops announced by the Centre to create jobs for migrants in the state, improve infrastructure and provide relief—all of which will help win over the poor before the polls.

The biggest challenge, however, is before the Election Commission, which has to figure out a way to hold the polls during a pandemic. “The elections may get delayed,” said Roy, “and currently it appears like it will be a hung house.”