Justice is a lonely being, often condemned to trudging long distances in search of an elusive truth which not only seems true but can also be demonstrated to be so.

On September 30, it completed a journey of 10,160 days to conclude that none of the 32 accused of having a role in the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya were guilty. The initial charges were filed against 49 people.

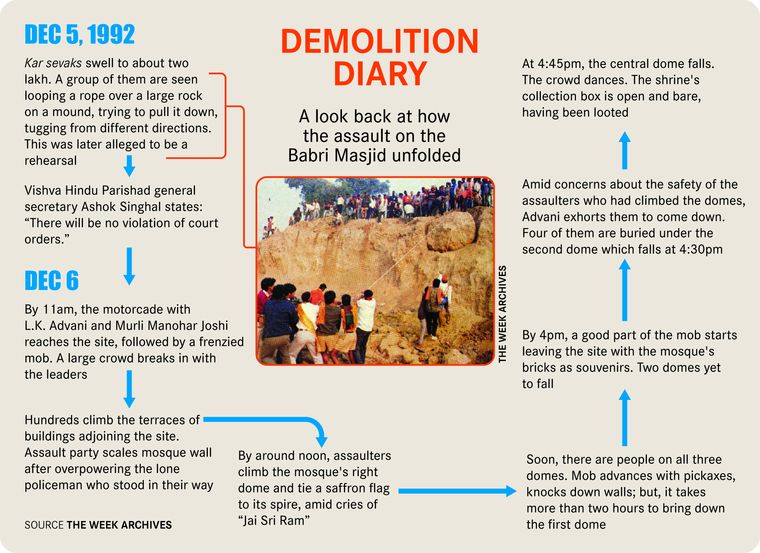

To the tunnel vision of justice, the prosecutors had failed to bring such conclusive evidence that proved beyond a shred of doubt the role of those accused—a list which included India’s former deputy prime minister Lal Krishna Advani and former Union minister for human resources development Murli Manohar Joshi. The judgment did not say that the demolition was not a criminal act, or that the accused were not present when it happened. It concluded simply that the evidence did not prove guilt on any of the multiple charges under the Indian Penal Code. These charges included wrongful assembly; causing voluntarily hurt to a public servant in the discharge of his duty; action with intent to incite any class or community of persons to commit any offence against any other class or community; and criminal conspiracy.

Krishna Kumar Mishra, one of the defence lawyers, said: “The reasons given by the court for the judgment are sterling. None of the evidence presented could be conclusively proven to be valid. The videos of the demolition, for instance, should have been seized, seizure memos prepared and the evidence sent for forensic testing. Instead the agency [Central Bureau of Investigation] randomly picked up evidence available from the market. It was not a failure of the investigating agency, but the circumstances were such that it was impossible to collect evidence in the midst of lakhs of people.”

The videos Mishra referred to were those available in the immediate aftermath of the demolition. They had contained grainy images of the domes being hammered by kar sevaks and brought down amid lusty cries of Ek dhakka aur do, Babri Masjid tod do (Give one more push and bring the Babri Masjid down). They remain available in public domain till date under titles such as ‘Shri Ram Janmabhoomi ka Raktranjit Ithihas’ (The blood-soaked history of the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi). Also, in evidence were scores of photographs provided by media persons. These were rendered useless by the non-availability of negatives.

The judgment throws into question the methods involved in the investigation. At one point it quotes a member of the investigation team as saying that the cassettes with the alleged inflammatory speeches were not sent for forensic examination as it was clear that the incident had happened. At another place it quotes an investigator’s contention that many papers were seized from the house of Shiv Sena leader Moreshwar Save, but a number of these were found not related to the case upon examination later.

The judgment dismisses all evidence provided through the media. For instance, in the case of then UP chief minister Kalyan Singh, the judgment says, “…the giving of a statement to a newspaper cannot be treated as acceptance or admission of a crime till strong evidence proves it”.

This is not a novel observation. In many cases, courts have held that newspaper reporting, whether correct or not, is hearsay secondary evidence and not admissible unless the reporter is examined or any person before whom the incident has occurred is examined, and facts proven.

Though a detailed reading of the judgment would require some time, Syed Mohammed Haider Rizvi, a Lucknow-based lawyer said: “On the face of it, the verdict acquitting all the accused and considering Babri Masjid demolition as a spontaneous incident and not a conspiracy comes in the teeth of the Supreme Court order dated November 9 , 2019, which clearly stated that the destruction of the mosque and the obliteration of the Islamic structure was an egregious violation of the rule of law.”

The accused on many occasions, and with pride, claimed their role in bringing the Ram Mandir Movement to its conclusion.

In his book Ayodhya 6 December 1992 , P.V. Narasimha Rao, the prime minister of India when the demolition happened, wrote: “The BJP took ‘moral responsibility’ for the day’s developments in a statement issued by the party’s vice president S.S. Bhandari. L.K. Advani and M.M. Joshi were among the prominent BJP leaders present in Ayodhya at the time of the demolition of the Babri Masjid. As the kar sevaks chipped away at the structure, BJP-VHP-RSS leaders had pleaded in vain with them to stop.”

But as the scales of justice are not tipped by morality, it remained unconvinced.

Mahant Raju Das of the Ayodhya’s famous Hanuman Garhi Temple said: “Ram Mandir is only the start. We will adopt constitutional means to free Mathura, Kashi and the Tejo Mahalaya.” The first is a reference to the Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi Temple at Mathura, the second to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi and the third to the Taj Mahal in Agra (which some consider to originally be a Shiv temple).

Sharad Sharma, the Vishva Hindu Parishad spokesperson in Ayodhya, however, said: “There is no dialogue on Kashi or Mathura. We are only celebrating. The Lord is truly free today.”

On the same day, however, in Mathura—which is supposed to be the birthplace of Lord Shri Krishna—a petition made its way through the court of the civil judge, senior division. It asked the court to declare that “land measuring 13.37 acres… vest in the deity Lord Shri Krishna Virajman” and the removal of “construction encroaching upon the land… and to handover vacant possession to Shree Krishna Janmabhoomi Trust….” Those are words with a strong similarity to those used in the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi- Babri Masjid title suit. The “encroachment” is refering to the Idgah Mosque and the parties being asked to remove it are Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Waqf Board and “Trust ‘alleged’ Shahi Masjid Idgah”. Notice the use of the word “alleged” by the plaintiffs.

This position runs contrary to the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 1991. The Act prohibits “conversion of any place of worship and… [provides] for the maintenance of the religious character of any place of worship as it existed on the 15th day of August, 1947”. The Ram Janmabhoomi at Ayodhya was the only exception, expressly granted by the Act.

Incidentally, the local court dismissed the Krishna Janmabhoomi petition, and the petitioners are now planning next steps. Ranjana Agnihotri, a Lucknow based lawyer who is among the eight plaintiffs to the suit describes herself (and five other co-plaintiffs) in it as “followers of vedic sanatan dharam, worshippers and devotees of Lord Shri Krishna…(who) profess, propagate and perform puja and other rituals of Lord Shri Krishna according to custom, traditions and practices of vedic sanatan dharam from the time of their ancestors”. It is their strong faith and belief that “dharshan puja at Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi is [the] way to acquire merit of salvation”. The first plaintiff in the suit is “Bhagwan Shri Krishna Virajman”. Just as was Shri Ram Lalla Virajman in the Ayodhya title suit—on which the Supreme Court adjudicated in November last year.

Agnihotri said: “We are only seeking to correct a long standing wrong. The birthplace of Shri Krishna has special significance and we are within our rights to protect it and demand recovery of lost property”.

The implications of the 2,300-page judgment on the Babri Masjid demolition, delivered by CBI judge, Justice Surendra Kumar Yadav, thus lie beyond his court.

In justice’s lonely journey, this then could be a temporary halt, not its final destination.