When HMS Hercules joined the Indian Navy as INS Vikrant in 1961, India became the first Asian power to have an aircraft carrier. That single carrier was enough for several decades, since no other Asian power wanted to control the Indian Ocean. Today, though, when the Chinese navy is projecting power with two carriers, while building a third and planning for two more, India is finding itself at sea.

India’s second carrier—Vikrant, which is the first to be made in India—is getting fitted at Cochin Shipyard; naval engineers have been drawing up designs for a third. But in February, Gen Bipin Rawat poured cold water on their blueprint. As chief of defence staff, whose job is to prioritise military procurement, Rawat questioned the wisdom of having three carriers. Carriers, he said, were expensive and vulnerable to torpedoes. He favoured submarines, citing the Navy’s worries about its dwindling underwater capability. Or, he asked, why not develop shore-based capabilities?

Rawat’s idea, apparently, is to build more submarines and develop islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea into “unsinkable strategic hubs”. He has left the call to the defence ministry, which he said might review its decision after INS Vikrant becomes operational.

The main argument against carriers is indeed their cost. India’s lone carrier in operation, the Russian-made Vikramaditya, cost a whopping 012,500 crore ($2.35 billion). Vikrant is expected to cost 019,590 crore ($2.8 billion). Its sister ship, which naval designers have been working on since 2012 and want to name Vishal, is expected to cost between 075,000 crore and 01.5 lakh crore.

Rawat’s comments have triggered a debate on whether carriers are white elephants. “They cost a packet and if hit by one enemy torpedo, all this will sink to the bottom of the sea,” said a Navy officer.

Abhijit Bhattacharyya, member of the London-based think tank International Institute of Strategic Studies, said: “Between a submarine and an aircraft carrier, the former is comparatively economical and safer to operate, is difficult to be detected, and does not require an accompanying flotilla of surface vessels.” He added that the visible deterrence provided by a carrier battle group was something a submarine could not achieve.

Unlike submarines, carriers operate in battle groups—with destroyers, corvettes and frigates accompanying them—and thus have no stealth element. They are visible, and therefore vulnerable, to ships, aircraft and submarines. Many maritime strategists, too, have been arguing for a submarine-centric force. The debate is as old as the start of the Cold War, when the US acquired carrier after carrier, while the Soviet Union went for fleet after fleet of silent submarines.

The trends led to two rival maritime doctrines—of sea control (by American carriers) and sea denial (by Soviet submarines). The rivalry and divergence got reflected in the Indian subcontinent, too. While India went for a carrier as far back as 1961, the Pakistan Navy put a premium on submarines. After the 1970s, however, India acquired submarines, too.

The doctrines also evolved out of geopolitcal compulsions. India, like the US, has a long coastline and, therefore, can have bases from where carrier battle groups can operate. Pakistan, like Russia, does not have much of a coastline, and thus cannot have many bases.

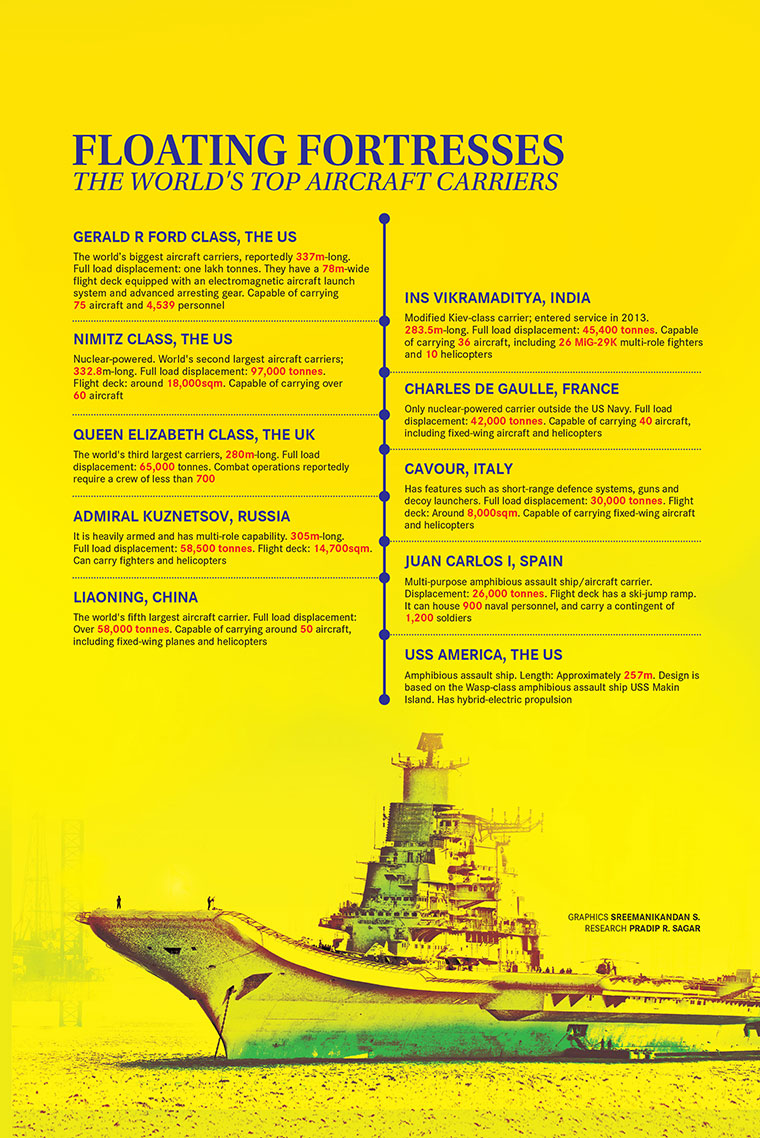

All the same, most modern navies are seeking to balance both types of assets (carriers and submarines) and doctrines (sea control and sea denial). The oceans now have 41 aircraft carriers that belong to 13 navies. The US operates 11 carriers and 70 submarines. The Russians and the British, having toyed with the idea of making do without carriers for nearly a decade, are coming back with one carrier each. The Royal Navy commissioned the 65,000-tonne HMS Queen Elizabeth and a second carrier, HMS Prince of Wales, is in its last leg of completion. Japan, which did not have any since World War II, now has three. Australia, France, Italy and Spain have one each. Even Thailand, which operates a helicopter carrier, HTMS Chakri Naruebet, may soon upgrade it to carry airplanes.

The latest argument against carriers is that even if sea control is the preferred doctrine, it can be achieved by developing islands as bases, from where aircraft, surface ships and submarines can patrol thousands of sea miles around. But carrier enthusiasts argue that carriers are essentially tools for projection of power (“100,000 tonnes of diplomacy,” as Henry Kissinger said), which cannot be achieved with shore-, submarine- or island-based platforms. Also, carriers have full-length flight decks capable of carrying, arming, deploying and recovering aircraft. A carrier battle group (CBG) that has destroyers, frigates, corvettes and submarines provides operational flexibility, with an ability to relocate up to 500 nautical miles in 24 hours. It can sanitise more than 200 nautical miles around it at any given time. Its primary missions can switch dramatically from air defence and strikes against surface ships, to strikes on shore targets and hunting submarines. “The US achieved air superiority in the Gulf War with the use of aircraft from carriers,” said a rear admiral.

India’s first Vikrant, a 20,000-tonne vessel, played a key role in enforcing the naval blockade of East Pakistan during the 1971 war, and its Hawker Sea Hawk planes struck Chittagong and Cox’s Bazaar. Its crew earned two Maha Vir Chakras and 12 Vir Chakras. Vikrant’s successor, Viraat, did not get a chance to bloody itself in combat, but threatened to starve Pakistan with a blockade of the Arabian Sea during the Kargil war.

General Rawat’s preference for shore-based facilities over carriers, said former navy chief Admiral Arun Prakash, was like comparing apples and oranges. “Shore-based strike has its own place to support naval operations and the aircraft carrier operating in the middle of the Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean has a completely different role to play. To show that shore-based facility is a replacement of aircraft carriers is a complete fallacy,” he said.

Naval officers say Rawat, being an Army officer, may not understand the imperatives of maritime strategy. “In an increasingly hostile operational environment, the aircraft carrier is the only platform that provides comprehensive access to littoral spaces, for surveillance and effective sea command,” said an officer.

The Navy has been maintaining that it needs at least three carriers to fulfil the increasing demands that are made on it every day. It is now being asked to police not only the Arabian Sea against Pakistan, but also the Bay of Bengal, and virtually the entire Indian Ocean from Malacca Strait to the Persian Gulf against the Chinese and other hostile powers, including pirates, gun-runners and terrorists.

While submarines are best for sea denial, carriers control seas and project power. “The carrier sits at the heart of India’s maritime strategy,” said Abhijit Singh, head of maritime policy initiative at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF). “Regardless of the debate surrounding [the new Vikrant], the Navy is unlikely to give up its demand for a third aircraft carrier.”

The Navy says the cost argument is fallacious. The 65,000-tonne Vikrant, it said, will finally cost about 049,000 crore (without the aircraft), but the money has been spent over 15 years. Moreover, as the ship is expected to serve around 45 years (twice the life of any other warship), “the cost is peanuts”, said the officer.

Vishal is expected to cost $7 billion to build, and the fighter jets, helicopters and reconnaissance aircraft will cost another $5-8 billion. Anticipating the high-cost objection, the Navy has already scaled down the number of fighters from 57 to 36.

While India is caught in the desirability debate, China is seeking to permanently position three or four warships and submarines, including a nuclear one, in the Indian Ocean. “It is only a matter of time that this task force is replaced with a CBG,” said an officer. “By 2028, there could even be two Chinese CBGs floating around.”

Said Admiral Prakash: “If China decides to send three aircraft carriers into the Indian Ocean, then no amount of submarines, destroyers or frigates can tackle it. Aircraft carriers are the only answer to such a situation.”

The Navy also points out that building a carrier is in tune with the government’s Make in India policy. Today, only a handful nations—the US, Russia, Britain and France—can design and build heavy (40,000-plus tonnes) carriers; India is one of them. “A carrier-building project generates a lot of industrial skills and jobs, especially in the micro, small and medium enterprises sector,” said an officer in the Navy’s design bureau. The money spent, said the officer, will be mostly ploughed back into the country.

Dr Harsh Pant, research fellow at ORF, said carriers should be prioritised over other capabilities. “It would boil down to an assessment of threat perceptions,” he said, “and what capabilities are best suited to manage them in the short to

medium term.”

The latest argument against carriers is that even if sea control is the preferred doctrine, it can be achieved by developing islands as bases, from where aircraft, surface ships and submarines can patrol thousands of sea miles around.