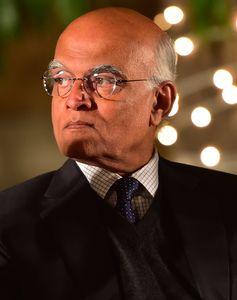

Shivshankar Menon’s much-anticipated book, India and Asian Geopolitics: The Past, Present, is a thought-provoking masterclass in understanding India’s foreign policy, its engagement with the neighbourhood and the way ahead. Menon, who had served as India's national security adviser, foreign secretary and ambassador to China, has written candidly about India's interactions in Asia, a region that is likely to determine the future of the world. In an exclusive interview with THE WEEK, Menon says creating a China-centric Asia will be difficult and that India and China need to both cooperate and compete.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

Q/ You said India was looking inward, which was a worrying strand, and cited it walking away from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) as an example.

A/ It seems to me that three things have happened. We have become much less committed to multilateralism, and it has happened over time. As we have become more realists, I think it is a reasonable response to what is happening around us. Multilateralism is delivering much less than it did in the 1950s. Our commitment to the global system has also gone down.

Secondly, as a reaction to globalisation, people tend to feel that their identity is threatened. The whole world is on your smartphone. Therefore, you go back to a nativist sort of system. You see this in the US, China, India, even Europe—the so-called traditional values, conservative politics of the right, of identity and going back to a mythical past. Globalisation has the opposite intellectual and political effect than what it should have had—to make you a global citizen. What I see is the closing of minds.

I don’t think we, in India, realise the extent of how dependent we are on the world. Almost 50 per cent of our GDP is in the external sector. We import our energy. We need the world for markets, for technology. We can say that we are the pharmacy of the world, but we are the pharmacy of the world when we are connected to the world. The best way forward for us is to be engaged with the world. But unfortunately, my fear is that we have gone the other way. The RCEP is the most prominent example, in which you negotiate for eight years and then walk out of the treaty. You are now the only major economy which is not part of any regional trading arrangement.

[Finally], atmanirbharta makes sense. We must be self-reliant. But if it starts shading into autarchy, then you have a problem. And it is easy for that to happen when it is allied with an ideology that tells you that you are unique, that you built aircraft 3,000 years ago. When you get into that frame of mind, your dealings with the world will become much more difficult.

Q/ You have talked about domestic compulsions. Do you think the rise of hindutva has affected our relations with the neighbourhood?

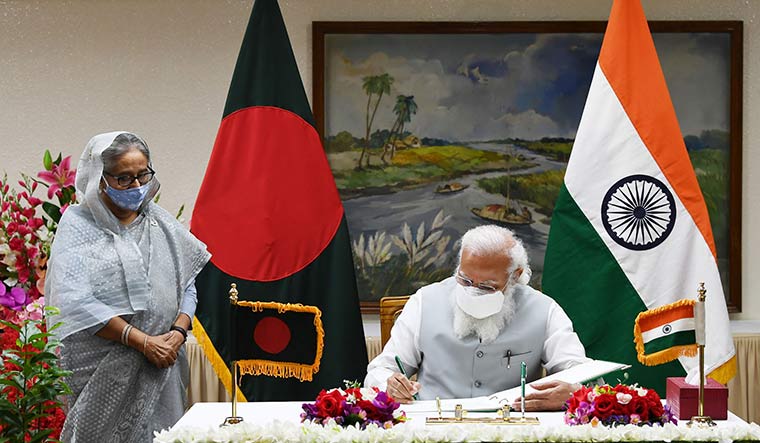

A/ There is public disquiet in our neighbours because they see an India which is different from the open, plural, secular, tolerant India they were used to. There was a period when our neighbours would look to us for models of governance. When the Sri Lankans were negotiating with the Tamils and various other groups, they looked to Indian federalism as an example. That is no longer the case. For me, that is a big loss because that affinity was very important. From a very practical point of view, [take, for instance,] Bangladesh: if you call people termites, you can’t really expect them to like you and not respond.

It seems to me that we are… still negotiating what kind of republic we want to be. We have a lot of internal arguments about this. But it cannot affect our standing outside because people see what we do. My worry is that we should not let our internal confusion be externalised into relationships that are more important and which really need careful tending.

Q/ You say you don’t see Asia becoming China-centric.

A/ China’s position, when you look at it geopolitically, is very different from that of previous global hegemons like Great Britain or the US. China is in a crowded neighbourhood. She is not the only country that is rising. She has two big established powers right next to her. On land, she has the greatest dispute with us, and [in] the maritime territory right through the South China Sea, [there are] flashpoints.

China always sees it to be contained, constrained and threatened. She spends more on internal security than she does on national defence. That tells me something about what the leadership thinks of the stability of their society. They have built, perhaps, the most effective surveillance state in the world, which makes me think that their priority is internal control, stability and regime security. Everything else, including the rest of the world, will be handled depending on how it affects them. It makes the idea of creating a China-centric Asia difficult.

Q/ How do you see the India-China relationship?

A/ If you look at the last 10 to 20 years, India, Japan, Australia, Indonesia—all of us cooperate more in defence, security and intelligence. This is a steady process. Many of us share concerns about China, but we don’t expect others to solve our problems with China. When we had a problem last year on the border with China, we did not turn to them. What we share with them is a desire for certain positive outcomes. We want freedom of navigation and maritime security and safety of our sealanes in the Indo-Pacific. [We are not] in a purely antagonistic relationship with China. We might be competing with China. But we are also cooperating with it.

Despite what happened on the border, in the first quarter of this year, India-China trade grew by 42 per cent over the same period last year. We have a very complicated relationship with China. On one hand we have the greatest boundary dispute with China, [and its] commitment to Pakistan has grown exponentially since 2015, but [on the other hand], China is our biggest trading partner. Secondly, China is a presence in our neighbourhood and the world, which we have to work with, work against or work around. But China is an actor we cannot ignore. There are things we need to both cooperate and compete [on]. We will have that kind of relationship.

Q/ Can we talk about Pakistan, a relationship which is adversarial? Every government has struggled with Pakistan, but this government has struggled a lot more.

A/ Every Indian government has tried to manage the relationship with Pakistan so that it does not distract us from the many more important things we have to do—transforming India and [also our] other relationships. Therefore, Indian governments tend to go back to the table. But Pakistan has always been hindered by its internal politics and its army, which has an institutional interest in a certain level of managed hostility towards India.

Today, our own domestic politics also leads some of those in power to believe that a managed level of hostility with Pakistan is useful domestically. You actually have a match here. The Pakistanis come to the table under two circumstances: they do it when they don’t have any choice—like [former president Pervez] Musharraf did in 2003 or when they think India is under pressure. I don’t know whether Pakistani politics can support a normal relationship with India, or whether Indian politics can support any major initiative with Pakistan at this stage.

Q/ Do you think it is better to manage the relationship with Pakistan than have no relationship at all?

My argument has always been to engage the parts of Pakistan that are not hostile to you. Why are we uniting all of Pakistan behind those who are hostile to us? We have no problem with the ordinary Pakistani, or Pakistani businessmen for whom business with India will be profitable, or even with most of the civilian politicians. So, for me, it does not make sense to lump them all together and follow one policy.

Q/ Do you think the way we handled the Covid-19 crisis has affected our international standing?

A/ I think the contrast between us claiming victory in 2020 and now is very stark. But the pandemic has diminished everyone. No one has come out of it well. Those who made grand claims were exposed and were probably diminished more. As I have always said, soft power is good only when it reflects an actual hard reality. It is not just creating an image and spreading a narrative. I have no idea why the MEA handled what happened with the Philippines embassy the way it did. All I have seen is what happened on Twitter. I don’t think Twitter is a good place to come to form judgments on…. Of course, it has damaged our image. But it has damaged the image of others, too.

INDIA AND ASIAN GEOPOLITICS: THE PAST, PRESENT

By Shivshankar Menon

Published by

Penguin Random House India

Pages 420; price Rs699