THE INDIAN government’s response to the Pegasus Project, a global investigative effort led by the Paris-based non-profit Forbidden Stories into instances of alleged surveillance abuses by governments, has been strikingly dismissive.

The government says that, contrary to what the Pegasus report alleges, existing laws in India make it impossible for authorities to put politicians, journalists and activists under illegal surveillance. Union Home Minister Amit Shah even termed the project as a conspiracy to destabilise the country. “This is a report by disrupters for obstructers,” he said, referring to opposition protests over the issue in Parliament. “Disrupters are global organisations which do not like India to progress.”

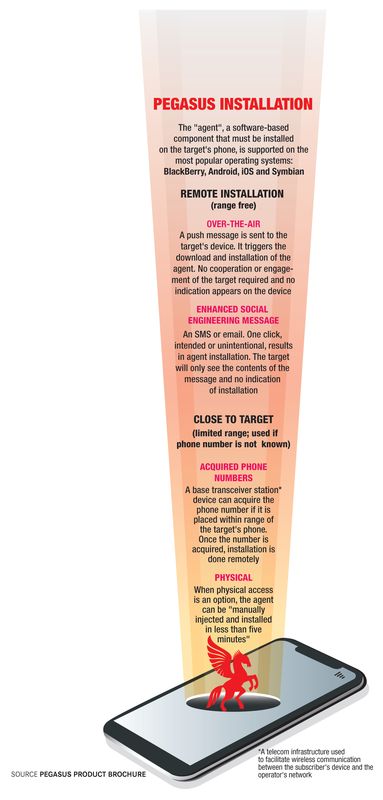

It is unsurprising that governments would deny—like they have done for decades—the use of illegal surveillance tools like Pegasus, a spyware developed by Israel’s NSO Group that allows security agencies to covertly infect smartphones and access content. The Indian government had earlier done so in 2019, when WhatsApp first confirmed that Pegasus was used to target some of its users in India and abroad. But then, it is a fact that many ministers and top officials now scrupulously avoid using smartphones. Also, government warnings of possible cyberattacks and confirmed incidents of spyware infections have been on the rise in the past two years.

The Pegasus Project reports that around 50,000 cell phones across the world were targeted by the Israeli spyware. Among the 300 victims from India are 40 journalists, two ministers and three opposition leaders. The shadow of suspicion is on the government, since NSO maintains that Pegasus is an anti-terror software sold “solely to law enforcement and intelligence agencies of vetted governments”. “Due to contractual and national security considerations, NSO cannot confirm the identity of our government customers,” said an NSO spokesperson.

The Indian government has denied unauthorised interception by security agencies. “In India, there is a well-established procedure through which lawful interception of electronic communication is carried out for the purpose of national security,” said a government statement. But then, there is a regulatory grey area since spywares are not part of the ambit of this lawful interception process.

Currently, there are 10 agencies in India that are authorised to carry out surveillance. The list includes the Intelligence Bureau, the Research and Analysis Wing, the Narcotics Control Bureau, the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence and the Directorate of Military Intelligence. According to the home ministry, all agencies have been following the old-school way of lawful phone tapping after obtaining mandatory permissions from state and Central authorities. There is also an oversight mechanism, whereby a committee headed by the Union cabinet secretary reviews all surveillance cases from time to time.

The Pegasus issue, however, has shed light on a grey area. The question is, how believable are claims that intelligence and law enforcement agencies shun advanced surveillance technologies developed by companies like NSO?

“Every government uses surveillance technology,” said a senior intelligence officer. “It is the job of a spy to spy in the best manner possible. For national security purposes, the government can withhold information related to [how spying is done]. We do not disclose field formations and weapons of armed forces; how can we disclose our cyber weapons and tactics?”

But apparently, there is no free rein to spy. “Surveillance technologies like Pegasus are extremely expensive and cannot be used for an unlimited period,” said an officer. “The targets have to be fixed, and the timeframe has to be short and precise, as high-end software can cost crores of rupees. One of them costs around 060 crore for a single use.”

According to Mumbai-based cyber law expert Prashant Mali, the government needs to urgently bring in a data protection law to regulate the purchase and use of surveillance technologies by security agencies. “There is a difference between buying and using [such technologies],” said Mali. “Intelligence agencies may not have bought Pegasus, but could have accessed it through a third party. This is where the role of a data protection regulator comes into play.”

Former national cybersecurity coordinator Gulshan Rai said targeted journalists must approach the Computer Emergency Response Team, the nodal agency that deals with cybersecurity threats in India, to conduct an independent forensic analysis of possible spyware infections. He also raised doubts about the authenticity of the forensic analysis done by Amnesty International in the Pegasus Project.

“Allegations were made by Amnesty; the forensic analysis was done by Amnesty; and the conclusion was drawn by Amnesty. Does it not raise doubts about the veracity of the case?” he asked. “The entire forensic report needs to be made public. An independent forensic analysis should be done to find out how the spyware’s signature was matched with that of Pegasus.”

Ultimately, though, the need of the hour may be a comprehensive bill to protect both data and privacy of citizens. The Personal Data Protection Bill, tabled in Parliament a year after the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in 2018 making privacy a fundamental right, is still stuck in Parliament.

“A right to privacy bill must be passed so that neither the government nor social media platforms can access and compromise an individual’s data without his knowledge,” said Rai. “I am against snooping by any government anywhere in the world. We live in a democratic country, where we are free to practice any profession, and express our opinions without fearing for our privacy.”

***

‘I am against snooping on citizens by any government’

Interview/Dr Gulshan Rai, former National Cyber Security Coordinator

Q\ After 2019 WhatsApp breach by Pegasus, this is the second instance of data breach. How is the government safeguarding the privacy of citizens?

A\ There is no mention of WhatsApp or any social media platform in the report of Amnesty. The released report is vague and does not stand on technical grounds. The versions of the software get updated over a period of time. The report is not specific on the version of software, the timing and number of attempts which were successful or not.

It is surprising that after Amnesty collected devices from those persons whose devices were reported to be hacked, the hacking could not be confirmed after the tests on the majority of those devices.

Either the entire testing process was wrong or something else is wrong. Amnesty needs to produce test processes and techniques used for testing. There is also no data on when the infection happened and when did Amnesty test the mobile devices.

In the earlier case, WhatsApp had filed a complaint against NSO Group in a court in California for sending malware to 1,400 users worldwide and that case is still continuing. However, WhatsApp said though there were attempts to hack into those accounts but it never acknowledged that the intrusions were successful.

Q\ If Pegasus spyware was found on mobile phones of journalists, ministers and government officials, isn't it a matter of concern?

A\ Amnesty International needs to come out and explain how did it recognise the Pegasus spyware? How did it come to the conclusion that it is Pegasus? Is Amnesty in possession of Pegasus?

Drawing conclusions on the basis of transfer of data from a device to a C2 domain is faulty. Anyone can register a C2 domain and transfer the data. The details of the owner of the said C2 domain need to be published. In this case, as it appears, the allegations have been made by Amnesty, the forensic analysis is done by Amnesty and a conclusion is drawn by Amnesty. Does it not raise doubts on the veracity of the entire incident? Where is the guarantee that devices were not infected by some other malware and that malware may be transferring data to the C2 domain? How did Amnesty differentiate between the two infections without a reference point? The entire forensic report needs to be made public. An independent forensic analysis should be done to find out the signature of the spyware and how it was matched with Pegasus.

Q\ Don't you think the government needs to inquire into the matter?

A\ Anybody can raise any allegation. On mere hearsay, the government should not launch an investigation. There should be prime facie evidence. These are very serious allegations and evidence needs to be made public. The individuals who claim their mobile phones were infected should approach the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) or any independent lab for a forensic analysis and provide test results to the investigating authorities.

Q\ The Parliament session has begun and the Opposition is alleging that the government is indulging in surveillance of its citizens.

A\ I am not getting into the politics of the issue but why is it that the release of the report by Amnesty and other international media organisations was timed just ahead of the Parliament session? It was clearly a targeted attempt aimed at the government. It was an attack on the democratic structure of the country. The reports, if true, could have been done in a normal course and not timed.

Q\ Don't you think there is an urgent need for a Right to Privacy Act?

A\ Yes. The Right to Privacy Bill should certainly be passed so that neither the government nor the social media platforms can access and compromise any individual's data without his knowledge. I am against snooping on citizens by any government anywhere in the world. We are living in a democratic country where we are free to practise any profession, speak and write our opinions without fear or favour and safeguard our privacy.