Every time her husband—a Cheetah helicopter pilot of the Indian Army’s aviation wing—goes flying, even for a routine sortie, Meenal Bhonsle makes it a point to see him off. “It could be our last meeting, we never know,” she says. “It is a traumatising day for me when he is flying.”

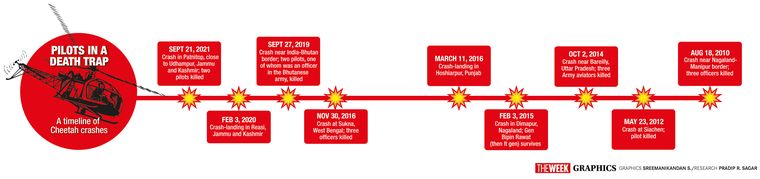

Over the years, the Cheetahs, which dominate the Indian military’s fleet of light utility helicopters (LUHs), have become a spot of bother. Last September, a Cheetah on a routine sortie crashed at Patnitop in Jammu and Kashmir, killing two Army officers. In February 2020, one crash-landed in Jammu’s Reasi area; there were no casualties. In 2019, another one crashed, killing two pilots—one from the Indian Army and the other from the Royal Bhutan Army—while flying over Sikkim, on the border with China.

Quite often, there are no roads to strategic heights like Siachen, making the Cheetah a lifeline for India’s high-altitude operations. The primary workhorse for the Indian military has been serving high-altitude areas in observation, surveillance, logistics and rescue roles.

But the fleet has been plagued by frequent crashes and serviceability issues. The Army Aviation Corps and the Air Force operate close to 200 Cheetah helicopters. There have been more than 30 crashes in the last few years and close to 40 personnel, including pilots, have died; several others have been wounded. Almost 80 per cent of these helicopters have outlived their lifespan of 30 years; the rest will cross the 50-year mark in early 2022. In a 2015 internal communication, the Army headquarters had said that Cheetah helicopters have virtually become “death traps”.

“We will continue to fly these coffins at least for next few years, as there is no immediate replacement available for these choppers,” says Lt Gen B.S. Pawar, former director general of Army Aviation Corps. He has clocked more than 4,000 flying hours in the Cheetah. “It has created a big void in the Indian military’s operational capability, from surveillance to casualty evacuation,” he says.

The Indian military was shocked by the crash of Mi-17V5 that killed chief of defence staff General Bipin Rawat and 13 others on December 8, 2021. The tri-services court of inquiry ruled out mechanical failure, sabotage or negligence. It attributed the crash to an unexpected change in the weather, which resulted in the “spatial disorientation of the pilot”. The reason given was Controlled Flight Into Terrain, which means the aircraft, while in complete control of the pilot, was inadvertently flown into terrain, water or an obstacle.

The Russian Mi-17V5 was considered to be one of the safest aircraft in the world, with glass cockpit features, cutting-edge avionics, including four multifunction displays, night-vision equipment, onboard weather radar and an autopilot system. The improved cockpit lessens the workload of pilots. Inducted between 2008 and 2018 and part of the Air Force’s VVIP fleet, it is usually used by the president, prime minister and other dignitaries to fly short distances.

In contrast, the Cheetah and Chetak are single-engine helicopters with obsolete avionics, lacking key features like moving map display, ground proximity warning system and weather radar. They also lack an autopilot system, which aggravates the chances of mishandling of controls in case of pilot disorientation in bad weather.

While the Chetak can only be operated in the plains, the Cheetah has proved its capability in remote and treacherous terrain. Military aviation experts believe that the Cheetah is unmatched in high-altitude operations. But they have passed their use-by date and the technology is not suited for modern warfare. Incidentally, General Rawat had miraculously survived a Cheetah crash in 2015.

The Cheetah, in its original French avatar, was the Aérospatiale SA 315B Lama. Months before the 1971 war with Pakistan, the Indian government placed an order for 40-odd helicopters with France, which included an arrangement for indefinite licensed production of the SA 315B by Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) at their facility in Bengaluru. The first Indian-assembled SA 315B flew on October 6, 1972, with deliveries starting in December 1973. The HAL-made helicopters were named Cheetah.

Group Captain R.K. Narang, a former Cheetah pilot, says that the chopper has been used to spy on enemy territory and collect information about suspected enemy locations for artillery gunners and fighter pilots. This is besides its supply role and medical role, where it has picked up injured and dead soldiers in less than ideal conditions. The best feature about these helicopters is that they can land anywhere and do not need a helipad.

During the Kargil war, Cheetahs reported enemy positions to base, airdropped supplies to troops in the Dras and Batalik sectors and evacuated several injured soldiers. Flight Lieutenant Gunjan Saxena and her colleague Sreevidya Rajan flew their Cheetahs over treacherous mountain terrain, amid heavy anti-aircraft fire from the Pakistan army.

But helicopter pilots say that each aircraft has a total technical life (TTL), and these choppers are flying way beyond their TTL. The airframe life of the LUH is about 4,500 hours, but most of the Army’s Cheetahs have logged over 6,000 flying hours. The engine life of the chopper is 1,750 hours and most have gone past that, too. Most have been overhauled at least five times, which is maximum for any aircraft engine. Getting spare parts is also a challenge, as their French manufacturers have shut down the plant. Owing to these, the strength of a helicopter unit has come down to three from five Cheetahs, with two helicopters per unit needing constant repairs.

Such issues have reduced the Army’s reconnaissance and observation capabilities by 25 per cent. “You cannot have a proper reconnaissance team,” says a Cheetah pilot. “Casualty evacuation suffers, as the chopper does not have the power to lift two casualties and a doctor along with it.” He adds that the helicopter’s radius of action has reduced as the pilot has to pick between carrying either load or fuel. To accommodate more people, pilots carry less fuel, which ultimately affects the helicopter’s range (distance or reach).

The Indian military has tweaked the Cheetah’s engine for its operational needs. The Indian military has been flying these choppers beyond the manufacturer’s permissible limit as it has no other option. In the Siachen glacier, the Cheetahs, which have a flying ceiling of 17,000ft, routinely fly at over 20,000ft, risking both man and machine.

In Siachen or high altitude areas, choppers are not allowed to fly after noon, owing to turbulent weather conditions. Post noon, these choppers are only cleared for mercy missions, which means casualty evacuation.

The Army and the Air Force need approximately 500 helicopters to replace the existing fleet of Cheetahs and to cater to operational voids.

The Indian military has been trying to replace its ageing LUH fleet for the last 20 years, but the acquisition process fell through because of repeated bribery scandals. Eventually in 2014, the defence ministry scrapped the Army’s contract to buy 197 such utility helicopters.

In 2015, during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Russia, India had inked an inter-governmental deal to procure 200 twin-engine Kamov Ka-226T helicopters, of which 135 were for the Army and 65 for the IAF. Even after six years, the contract is stuck in negotiations between HAL and Russia.

Meanwhile, HAL is developing its LUHs, the first four of which are expected to be manufactured by late 2022. The defence ministry approved the procurement of 12 LUHs from HAL for around Rs1,500 crore, but the formal order is yet to be issued.

Even as they wait for new helicopters, pilots continue to fly the vintage Cheetahs. Meenal Bhonsle and 120 other women whose husbands are part of the Army’s Aviation Corps have formed a group called Indian Army Wives Association. The group has been raising the issue of obsolete Cheetahs at multiple platforms. “We lead a highly stressful life,” says a member. “We have been assured by higher authorities that the Cheetah fleet will be replaced soon. But, there is hardly any development on the assurance, and pilots continue to fly them.”

Lt Gen Pawar says that a few months ago, the military raised an alarm over the Cheetah helicopters. It shows the gravity of the situation, as all Cheetahs would complete their extended lifespan by 2023. He says it will be next to impossible to service troops in Siachen, the world’s highest battlefield, without LUHs like Cheetah.

Though other choppers can drop rations, casualty evacuation would demand a nimble player like the Cheetah. “Our troops’ deployment is maximum on high-altitude areas of the Himalayas and I am worried in case a war breaks,” says Pawar, adding that India is not going to fight its next war in the plains.

Pawar suggests the government look at leasing a few helicopters already available in the market to tide over the crunch. “This is a viable option,” he says, “and needs to be explored by the government, till our forces get new choppers manufactured in India.”

Meanwhile, the armed forces got advanced light helicopters (ALH), designed and developed by HAL. But these helicopters can only fly to a certain ceiling. In August 2021, an ALH flying over Ranjit Sagar reservoir near Pathankot crashed, killing two young pilots.

Harish Chander Joshi—father of Jayant Joshi, one of the two pilots who died—wrote to President Ram Nath Kovind demanding accountability for the crash and stressing the need for immediate corrective action. In his letter, Joshi claims that the crash exposed glaring gaps in the safety processes followed by the Army Aviation Corps, and also revealed apathy and disregard for pilot safety and training needs.

“I have lost my son and he cannot return,” Joshi tells THE WEEK. “But I want the Army to take corrective measures so that no one else loses their son or husband.”