India’s criminal justice system is undergoing a major churn. The legal edifice built by the Britishers is being replaced brick by brick, with laws that are in sync with modern times and Indian conditions. Home Minister Amit Shah and Law Minister Kiren Rijiju are the architects, and have been brainstorming for the past one year to bring about this paradigm shift. In focus are the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860; the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973; and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

On April 18, President Ram Nath Kovind gave his assent to the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Bill, 2022, ushering in the first big change. Opposition parties and critics called the legislation “draconian” and “unconstitutional”, and said it could be used to create a surveillance or police state. Policymakers and law enforcement bodies, on the other hand, called it a progressive law that brings Indian agencies at par with their counterparts in the US or the UK.

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation, for instance, has a centralised database of even shoe prints. “The US Secret Service has a database on almost every article today. Digital prints are available for everything from a shoe and wall paint to a deleted tweet,” said senior IPS officer Muktesh Chander, former director of the National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre in Delhi. With this, sleuths can match the shoe prints at the crime scene with their central database, identifying the makers and when that particular shoe was sold from which outlet in which part of the country.

“India needs to keep pace with the changing times where the five big technology giants like Google already have a database of individuals,” said Chander. “We have only taken a baby step in that direction.”

He added that the new law would help the government achieve the “one nation, one database” mantra wherein the National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID) and Crime and Criminal Tracking Networks and Systems (CCTNS)—which links data records in every police station in the country—will get a wider array of details including even sweat and semen matches in cases where the offence attracts a jail term of more than seven years.

Currently, different government bodies keep different details. For example, the Election Commission and passport authorities have photographs of citizens, and the Aadhaar database has iris scans. During the 2020 Delhi riots, the Delhi Police had asked the Election Commission for access to its electoral rolls to match the faces that were captured on CCTV cameras. After public furore, the commission had to clarify that it had followed legal guidelines to assist the law enforcement agency. A senior home ministry official said the IPC and the CrPC allow the government to seek any information from other departments in matters of national security.

Y.C. Modi, former chief of the National Investigation Agency, said the new law would certainly help in speedy investigation. “Crime is a dynamic situation and criminals are adopting new methods every time,” he said.

The NIA’s probe into the 2019 Pulwama terror attack had begun as a blind case in the absence of any proof against the perpetrators. The agency collected more than 4,000 fingerprints, but did not have a corresponding national database to cross-match. Finally, it used DNA profiling and other forensic tests to identify Adil Ahmad Dar as the suicide bomber who had rammed the explosive-laden car into the Central Reserve Police Force convoy. The biological traces were the only evidence left on the spot of the carnage.

“A lot of information is already available with the government and police agencies directly or indirectly,” said M.L. Sharma, former CBI special director. “So, the problem is not who will access it, rather what kind of personal information should they access keeping in mind the nature of the crime. It is this thin line that makes the law draconian.”

He, however, said the constitutional validity of the current law cannot be questioned. “No doubt, privacy is a fundamental right, but it is not absolute and it is subject to the dictates of law and order and public peace,” he said.

Where the law flounders, Sharma said, is that it permits taking measurements like fingerprints and retina scans in all offences, even petty ones. “The act says only biological samples cannot be collected for lesser offences,” he said. This could intrude into the privacy of citizens, he added.

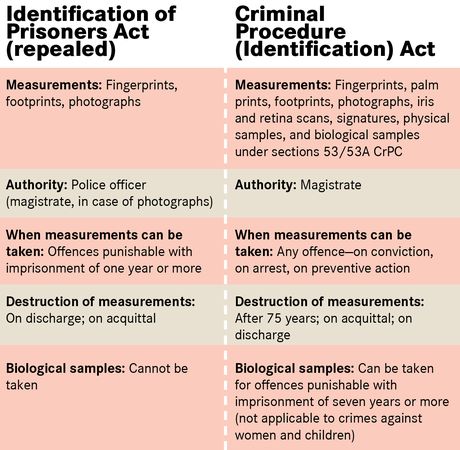

The Identification of Prisoners Act, 1920, which has been repealed, covered only those offences that were punishable with at least one year of jail and only included fingerprints, footprints and photographs. “The current law may be conducive to public order, but the rigour of this law should be applied only to serious offences that are cognisable and punishable with imprisonment of three years or more,” said Sharma.

Prashant Mali, a cyber crime lawyer in the Bombay High Court, said that, under the new law, the measurements of a person may be used against him in trial. However, Article 20(3) says that a person cannot be forced to be a witness against himself.

Moreover, if a person is granted bail, he can still be arrested if he refuses to provide the measurements as per the new law, he said. “The purpose of the bail provisions will be defeated,” he said.

Experts also feel the implementation of these provisions would burden the police in routine cases. It would also entail considerable public expenditure without corresponding gain to public peace.

Former home secretary G.K. Pillai recalled that the collection of biometrics for the Aadhaar database had to be scrapped some years back as the technology was not easily available at all centres. There was also the problems of authentication and storage.

“Lastly, the new law also needs to be in sync with the proposed data protection law that is aimed at making citizens aware of their right to consent in the ever-evolving digital ecosystem. Accountability will have to be fixed against misuse or leak of personal data,” he said. The government will also have to specify what kind of measurements will be preserved for 75 years, which could last the entire lifetime of the accused.

The devil lies in the details. Said Pillai: “Technology alone cannot control crime. So while the new law will provide a tool to police forces and Central agencies to track criminals and crack cases, the lawmakers and law enforcers need to be equally focused on regaining the credibility of the institutions using these tools.”

Inter-agency rivalries, centre-state battles and leakage of critical details in sensitive cases are some of the ills plaguing the criminal justice system today. A glaring example is that almost all opposition-ruled states have withdrawn their consent to the CBI to investigate cases in their states. “The bill is very wide and ambiguous and can be misused by the state and the police. It is against the right to be presumed innocent till proven guilty,” said Congress leader Manish Tewari.

Said Pillai: “The trust deficit between the Centre and states needs to be bridged first, and the Central agencies need to win the confidence of the people for successfully implementing any law.”