Faith, that amorphous being of unpredictable consequences, is winding through the district court of Varanasi. The court is tasked with deciding whether a petition seeking worship rights near the western outer wall of the Gyanvapi mosque is maintainable.

The petition, filed in August 2021 by five Hindu women (Rakhi Singh, Laxmi Devi, Sita Sahu, Manju Vyas and Rekha Pathak), follows the nebulous nature of faith. It essentially seeks rights for the daily worship of a deity—Ma Shringar Gauri—outside the mosque’s western wall. Currently, devotees are permitted to worship the deity only once a year. The petitioners want that “no interference be made” while worshipping “visible and invisible deities, mandaps and shrines” on the Gyanvapi premises, and that “the images of deities be not damaged, defaced, destroyed and no harm be caused to them”. They term the area as an “old temple complex” that was almost completely destroyed on orders of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the 17th century.

The petition would not have attracted the kind of attention it got had a senior civil judge not ordered an inspection of the disputed site by three advocate commissioners. There had also been a pending petition, filed by the Hindu side, to get the area inspected by the Archaeological Survey of India.

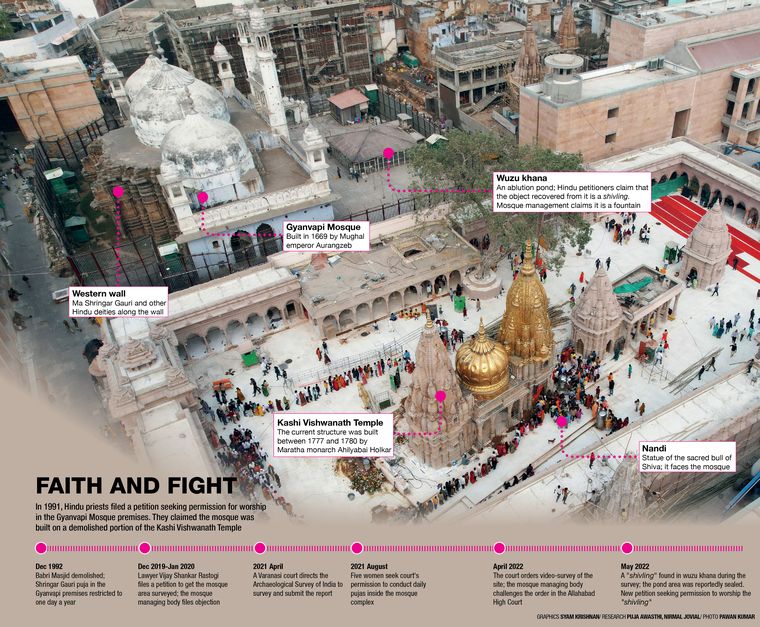

During the inspection, a circular object apparently made of stone was recovered from the wuzu khana (ablution pond) of the mosque. The petitioners have since been insisting that it is the original shivling (the phallic representation of Shiva) of the temple destroyed by Aurangzeb. Bolstering their claim is the longstanding assertion that a statue in the temple side of the complex—of Nandi, the sacred bull of Shiva—faces the mosque instead of the shivling in the adjacent Kashi Vishwanath temple. Nandi is always shown facing Shiva, so the position of the statue is cited to indicate that his master resides within the mosque, awaiting discovery. Interestingly, the petition has no mention of a shivling.

The symbolism of five married women asking for the right to worship a Hindu goddess outside a mosque is obvious. Whether the petitioners are legally literate, however, is not. “I cannot recall what the petition says,” said Sita Sahu, one of the petitioners. “For that, I trust the lawyers. I only know that it cannot be right that we can worship Ma only on one day in a year.”

That one day is the fourth day of Chaitra Navratri, the nine-day worship cycle of different forms of the goddess. It falls somewhere between April and May, depending on the lunar calendar.

The petition mentions “invisible” deities, but Sahu could not explain what it meant. She said there could be several other deities “hidden” in the mosque. She was also not sure whether there was a formal ban on worshipping Ma Shringar Gauri on other days of the year. (There is no legal ban, apparently; but the authorities have not been permitting daily devotions since the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992.)

Lawyer Abhay Nath Yadav, who represents one of the respondents in the case (the Anjuman Intezamia Masajid Committee, the managing body of the mosque), said the plaintiffs were speaking in a language that was emotional but not legal, and that the courts could not be run on mere feelings. Yadav pointed out that Ma Shringar Gauri’s image exists almost eight feet beyond the barricades on the mosque premises. “It is completely outside the mosque, and the Muslim side does not have any claim on it,” he said.

The petition mentions a civil suit filed in 1936, by one Deen Mohammed, asking for the Gyanvapi complex to be declared a waqf site. The petitioners argue that the 1936 case was heard without “impleading any member of the Hindu community”.

The argument appears tenuous, though. Yadav said the petition quotes the details of the case only selectively, and that it ignores the judgment entirely. “The judgement took into account 12 witnesses who attested to the presence of Ma Shringar Gauri and noted that ‘only the mosque and the courtyard with the land underneath are Hanafi Muslim waqf’,” said Yadav.

Sudhir Tripathi, a lawyer for the petitioners, said the claim of the Hindu side was “very strong” and that religious texts such as the Skanda purana (named after Skanda, son of Shiva and Parvati) can be used as evidence. During the hearing of the case on May 23, Tripathi sought copies of thousands of photographs and hundreds of hours of video footage shot while the advocate commissioners carried out the inspection of the Gyanvapi premises. “The inspection is our strongest evidence,” he said. “We need to examine it in its entirety to ensure that whatever we have asked for has been carried out and reported.”

Asked why the object that has now been ‘discovered’ was never spoken of earlier, Tripathi said, “It was Baba’s (Shiva) decision that it must be revealed now. It was Baba who inspired me to insist that the wuzu khana be emptied.”

Interestingly, the report of the commissioners does not refer to the find in definitive terms. It calls the object a “black, circular, stone-shaped figure… 2.5ft in height… On its top was a circular white stone with a round hole in the middle which was little less than half an inch…. The diameter of the base was found to be about 4ft.” The petitioners insist that this is a shivling; the respondents say it is an out-of-use fawarra (fountain).

Rana Pratap Bahadur Singh, a retired professor of cultural geography at the Banaras Hindu University, drew attention to the oldest known drawing of the Kashi Vishwanath temple complex, made by the antiquarian James Princep in 1833. Princep’s drawing does not show a Nandi. Though Princep’s work has not been challenged, his reconstruction draws from the Kashi Khanda, a nearly 600-year-old text that does not fit in with the existing architectural practices. It is also true that the Kashi Vishwanath temple is built in a style that is different from similar, contemporaneous structures.

“It is almost impossible to ascertain where the original shivling or the temple was,” said Singh, whose own research indicates that the oldest archaeological remains, dated fifth to sixth century BCE, are found at the Rajghat in the northeastern part of the city. These remains include a seal of Avimukteshvara, symbolising a form of Shiva who had not forsaken sacred territory. By the 12th century, however, this deity had been relegated to the margins.

The difficulty in ascertaining the original site of the shivling is also compounded by the fact that the original temple was destroyed multiple times. According to one legend, a temple priest leapt into a well in the compound to save the shivling, while another says that it was taken to Indore and subsequently restored to its original site by the Maratha queen Ahilyabai Holkar. It is this site that is now worshipped.

The inquiry of the commissioners also throws up curious questions. Such as, if the original shivling is in fact the one discovered in the wuzu khana, what is the sacred status of the one that is worshipped now? Is it then not one of the 12 jyotirlings (pillars of radiance) of Shiva? Or, does the discovery mean that there are 13 such jyotirlings.

These are cosmic concerns, though. There are more earthly questions that worry the youth of the city. Sabi Uddin, a final-year BA-LLB student at BHU, said that the flare-up of the issue had left him “disappointed”. Matters that were more important—such as shortage of potable water and the poor condition of roads—needed be addressed, he said.

According to him, the Supreme Court had rightly observed in a 1994 case that mosque was not an essential part of Islam. “It is not space, but the direction that is of importance for the namaz,” said Uddin. “This is a live matter which I hope the courts will resolve at the earliest.”