Italy First. Across the world, variations of Donald Trump’s slogan have catapulted new governments into power. In Italy, the slogan achieved not only an electoral triumph, but also two other firsts. Giorgia Meloni is expected to take over as Italy’s first woman prime minister, and her party, Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), will be the first far right party to come to power in Rome since the days of fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

Meloni’s right wing coalition includes former deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini of the Lega party, and Forza Italia leader and former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi—he of the notorious “bunga bunga” parties with pole-dancing strippers dressed as nuns. This unholy trinity is nationalist, populist, anti-migrant, homophobic, Islamophobic and Eurosceptic. The European Union is worried that the trio could disrupt the ongoing economic reforms, spread illiberalism and try to alter the course of the Ukraine war. “Italy could really create problems for the EU,” said Stefano Stefanini, Italy’s former ambassador to NATO.

Italy is the EU’s third largest economy, its third most populous country and the second most indebted. Its massive, unsustainable debt revives nightmares of the 2012 Greek debt crisis that nearly wrecked the bloc. To bag the EU’s €200 billion Covid-recovery aid, Italy has pledged reforms. The EU calculates that Italy’s abject dependence on this aid will prevent Meloni from reneging. Meloni, meanwhile, has chastised the EU for freezing funds to Hungary and Poland for their illiberal, anti-democratic policies. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, has warned that the same “tools” will be used against Italy if it drifts towards illiberalism. “Italy will exit from the core of Europe. The European future will be less strong and less secure with Meloni,” said former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta.

On Ukraine, the EU’s concern is that Meloni and her coalition partners have varying degrees of personal and party links to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Italy is also dependent on Russian gas, which has resulted in skyrocketing energy prices. Said Salvini, “Europe chose to impose sanctions on Russia. That is fine, but the price of sanctions cannot be paid by Italian families and businesses.”

To soothe nerves, Meloni has reiterated her support for Ukraine. While she riles against EU’s “interference”, Meloni, like most far right leaders, admires military muscle and supports NATO. Experts hope that power will moderate or discredit her coalition partners as they start squabbling over turf and policies. But no one can be sanguine after the Trump experience. Steve Bannon, Trump acolyte and Meloni fan, is bullish: “I have said for years that Italy is the worldwide laboratory for the populist-nationalist revolution. Meloni is going to transform Italy from a failing, stagnant, bankrupt mess into Europe’s strongest economy with jobs and prosperity for all.”

Unlikely. Voter turnout in the national elections held on September 25 was a low 64 per cent. Italy is split down the middle. Animosity between the left and the right runs deep. “The so-called progressives use the power of their mainstream media. They want a right wing on a leash, trained as a monkey,” said Meloni. Leftists warn the far right will curb personal freedom and democratic rights. They say Meloni and her team lack the experience and competence to navigate the economic crisis. “If you do not deliver economic growth, the endlessly protesting Italians will vote you out,” said economist Carlo Bastasin.

Fed up with corrupt, incompetent governments, voters have experimented for decades with new anti-establishment parties. Berlusconi, Salvini, the Five Star Movement, all started with less than 4 per cent vote share, only to get 25 per cent to 37 per cent within a decade and rule. Meloni got only 4 per cent in the 2018 elections, but now its her turn to try to revive the economy and solve the cost of living crisis. “Meloni has understood perfectly that Italians are sick of bombast. What we are going to see is ‘Italy First’,” said political analyst Catherine Fieschi.

Meloni’s 2019 speech in Rome has come to define her. “I am Giorgia, I am a woman, I am a mother, I am Italian, I am Christian,” she said, touching all the ‘Italy First’ chords. DJs remixed it into an absurd techno-dance track that got over 12 million YouTube views. It was intended to mock her. Instead, Meloni’s popularity flew off the charts.

Meloni plays the conservative, religious card well, but her Christian, family-values are dubious. Her party’s anti-immigrant policy—withdrawing housing and food vouchers to immigrants during the pandemic—was described as “criminal” by one of her political opponents, Pierluigi Iannarelli. Pope Francis pointedly urged the new government to show “compassion” to immigrants. Meloni retorted that she did not understand this pope.

It is also hard to see traditional family values in Meloni’s personal life. She chose not to marry the father of her six-year-old daughter. A firebrand opponent of abortion and homosexuality, Meloni woos Catholics. But Italy is not very Catholic these days. Abortion is legal.

Embodying the rough and tough, no-nonsense street fighter spirit of the working class, Meloni was a nanny, a waitress, a nightclub bartender and a journalist before becoming a politician. She is feisty and fresh, a striking contrast to the dreadful parade of male Italian prime ministers who were mostly boring, bureaucratic or burlesque. “People respond to Giorgia because she is authentic and fierce,” said Alberto Rocco, a voter.

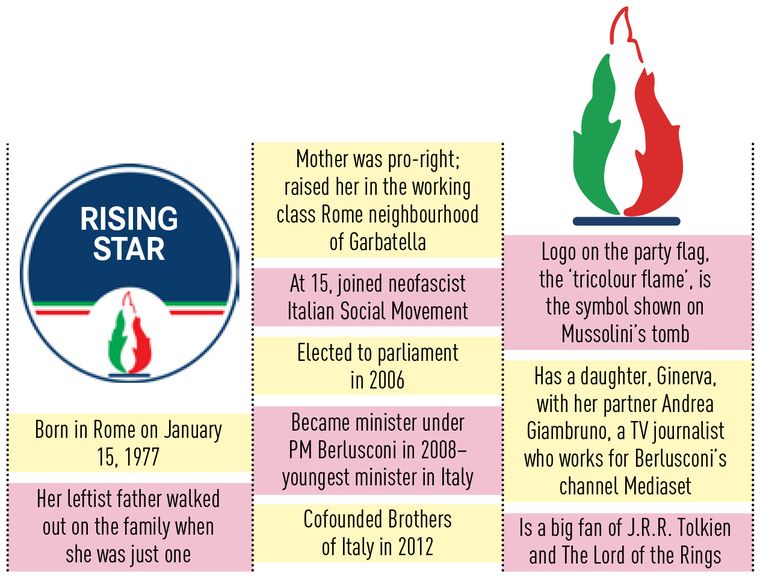

Though her party has neofascist roots, Meloni rejects being labelled far right. She calls her party “mainstream conservative”, sharing values with conservative parties in Israel, the UK and the US. That probably indicts more than it absolves. The name of the Brothers of Italy party that she cofounded in 2012 is taken from the Italian national anthem and the logo on its flag, the “tricolour flame”, is the symbol represented on Mussolini’s tomb. “It is a mistake to write off these movements as ‘nationalist’, drawing a straight line back to the horrible history of fascism and Nazism. Something else is at work. Italians want a responsive government,” said John Farina, who teaches religious studies at George Mason University, Washington, DC.

Italy’s broken politics is the evil twin of its broken economics. Reconstruction in the post World War II years helped Italian economy boom. It began stalling in the 1990s, and after the 2008 financial crisis, Italy’s negative growth led to declining living standards, aggravating political instability. Said economist Eric Basmajian, “The ongoing Italian crisis is a toxic cocktail of excessive debt, political instability and poor demographics. Italy is running out of people.”

Italy’s working population is declining. Poor growth makes it harder for young people to advance their careers, buy a home or start a family, resulting in declining fertility rates, lower births and a baby bust. Young men do not marry because jobs are hard to come by. Nearly 45 per cent of them prefer to live with their mothers.

In 2020, Meloni was elected president of the European Conservatives and Reformists Parties, comprising more than 40 ultraconservative political entities, including the Republican Party of the US. She can galvanise the masses as she is a grassroots leader with far right credentials. Fluency in English, French and Spanish enables her to spread her wings in Europe, strengthening linkages in Hungary, Poland, Spain and France and forming a bloc within the EU to challenge Brussels over issues related to democracy and rule of law.

Those who know Meloni say power is unlikely to rein her in. Valerio Alfonso Bruno, who is writing a book on Brothers of Italy, predicts trouble ahead. He expects Meloni and her international allies to create an illiberal Europe that deprives women, gays, immigrants and other minorities of their civil rights. For Europe, a bastion of liberal democracy, this would be a catastrophe.