The deep seas make up 95 per cent of all the space available for life. Yet, we know more about the surface of the moon than about the deep-sea plains. According to the nature documentary, Our Planet, until recently, we used to think the deep supported little life. But now, scientists believe there are 10 times more animals living here than previously thought. Like the dragon fish, which uses bioluminescence to attract prey to its terrifying teeth. Or the deep-sea angler fish, which uses an array of sensors to detect the movement of its victims. Or the chimaera, an ancient relative of the shark, which conserves

energy by slowing its pace on the barren sea floor.

Two years ago, I was privileged to see one of the deep-sea wonders in a glass jar―a strange shrimp-like creature with spindly legs and a clear and translucent body. “It is a hadal amphipod,” British businessman and adventurer Hamish Harding told me over Zoom. “They are creatures you can find only at the bottom of the ocean.”

This was in July 2021, four months after he and undersea explorer Victor Vescovo had set two new Guinness World Records―for the longest distance traversed at the bottom of the ocean (4.6km) and the longest duration spent there (four hours and 15 minutes). Harding and Vescovo were among the handful of people who had travelled to the deepest part of the ocean―a small valley called the Challenger Deep at the southern side of the Mariana Trench, 11km under the surface of the ocean. He had collected the amphipod from there.

“The pressure down there is 1,200 times more than the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level (equivalent to the weight of 8,000 double-decker buses pushing down on the submersible),” Harding told me. “These creatures survive by evolving bodies that allow the water to flow through them, to equalise the pressure. Nature cannot create a shell that is strong enough for them to withstand such pressure.”

The passion in his voice was palpable. Yet, there was something measured in it, too. As though the magnitude of his undertaking had sobered him. His triumph was not that of mere thrill-seeking. There was a deeper and weightier dimension to it. I wonder now whether he ever saw the end coming. People who habitually risk death must have an intimate relationship with it, right?

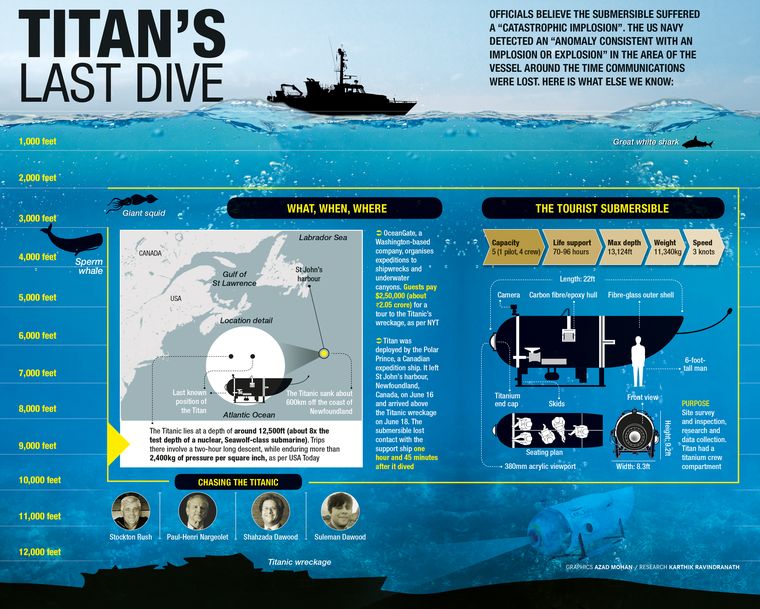

On June 22, the US Coast guard declared that Harding, along with the four others onboard the Titan submersible, were believed to be dead. The submersible had lost contact with its support ship, the Polar Prince, during a dive to the Titanic wreckage site in the North Atlantic on June 18. It had been 3.5km below sea level. Its hull is believed to have collapsed due to the intense water pressure, leading to a catastrophic implosion. Onboard with Harding were Stockton Rush, the founder and chief executive of OceanGate Expeditions, the company that operated the submersible; Paul-Henri Nargeolet, a former French naval captain known as Mr Titanic due to his expertise of the sunken ship; and the father-son duo of Shahzada and Suleman Dawood, members of one of Pakistan’s wealthiest families.

The extensive media coverage for the submersible’s search operation did receive its share of criticism. Why was so much attention paid to the ultra-rich billionaires who might have “brought the tragedy upon themselves” and so little to the hundreds of migrants who lost their lives when the boat on which they were travelling sank off the Greek coast on June 14? asked the critics. Why were the explorers even allowed to travel in an uncertified vessel which, according to many reports that emerged subsequently, was flawed in its design? Finally, why would they want to go somewhere as dangerous as the bottom of the ocean to see a shipwreck and indulge in what many described as “grave tourism”?

To answer that, one must go beyond the simplistic notion that they were merely thrill-seekers who were risking their lives for the sake of bragging rights. If that were so, they would not have staked their wealth, their reputation, and their time on this pursuit of new discoveries. Rush, for example, became the youngest person in the world to qualify for jet transport rating, the highest pilot rating obtainable, at the age of 19. Although initially he wanted to be the first person on Mars, he later realised that what thrilled him was not space, but exploration. “It was about finding new life-forms,” he said in an interview to CBS. “I wanted to be sort of the Captain Kirk [from Star Trek]. I didn’t want to be the passenger in the back. And I realised that the ocean is the universe.” In 2009, he founded OceanGate, a tourism and research company that offered trips to the deep sea at a price of $2,50,000 per trip. Interestingly, Rush’s wife, Wendy, is the great-great-granddaughter of Isidor and Ida Straus,

two first-class passengers in the Titanic. Ida apparently refused to leave her husband and get onto the lifeboat, and the two were seen standing together on the deck of the sinking ship.

As for Nargeolet, who was one of the world’s foremost experts on the Titanic, his love for wrecks was triggered by his first dive in Morocco, when he was just nine years old. In 1987, he led the first recovery expedition to the Titanic. Since then, he has completed 37 dives to the site of the wreck and supervised the recovery of 5,000 artefacts from it.

It is also not that these men were rash adventurers who did not calculate the risks of what they were doing. Harding, for example, knew exactly what he was getting into. “If something goes wrong, you are not coming back,” he told me then, describing some of the dangers of their Challenger Deep mission, like how the thrusters they were using to move around could hit the silt on the floor of the ocean, which could potentially cloud their view. Then there was the risk of them getting entangled in the cables left there by the remotely operated vehicles of different countries. But the biggest threat they faced was when they suddenly discovered an unmapped undersea mountain the size of Table Mountain in Cape Town. “We encountered it while heading off in a direction that looked interesting on the sonar map,” he said. “Remember that there is no rain down there to weather down mountains, which tend to stay the way they were created. We did not know the cliff was there, because no one has been to that bit of the trench before.”

English writer G.K. Chesterton once said that the world would never starve for want of wonders; but only for want of wonder. In this chaotic and tech-driven world, this is true of most of us. But not of these men. Their own impassioned descriptions of their experiences show that they were drunk not on thrill, but on wonder.

Take the way Nargeolet describes the hushed awe he felt the first time he saw the wreck of the Titanic. “Using the sonar, we approached and, behind a mound, the hull appeared,” he told Le Parisien. “There were the anchor chains, the winches still shining, polished by the current, lit by our searchlights. A fantastic picture. We were overwhelmed, speechless. For ten minutes, there was no sound in the submarine.”

Whether it was Nargeolet’s search for the site of the mythical city of Atlantis or Shahzada’s work with the SETI Institute (which searches for extraterrestrial life) or Harding’s circumnavigation of the earth via the North and South poles, these men seem to have been wired a little differently. For them, this world was never enough. They were constantly hammering away at it, as though they had an inkling of what lay beyond. “Don’t adventures ever have an end,” Shahzada wrote in a Facebook post after a trip to Iceland, quoting Bilbo Baggins from The Fellowship of the Ring. “I suppose not. Someone else always has to carry on the story.” So long, gentlemen! It is time for the story to move on.