On October 6, 2003, US deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage huddled with Pervez Musharraf at the presidential palace on the highly guarded Constitution Avenue in Islamabad. As he was heaping praise on Musharraf and Pakistan’s military brass for their efforts to dismantle the terror infrastructure in the country, a few kilometres away a car was stopped by a few armed men. Within seconds, the passenger’s body was riddled with bullets, and he fell in a pool of blood. The assailants fled, without leaving any trace.

The victim was Azam Tariq, head of the banned Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, who was on his way to Islamabad from Jhang. And he was just one of the dozens of extremists eliminated by unknown killers in Pakistan in a few months.

Those were not ordinary times. Stung by the 9/11 terror attacks, the US had forced Islamabad to take action against Taliban and Al Qaeda militants, and masked men battering targets beyond recognition had become the new normal on Pakistani streets. Riaz Basra, founder of the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, was killed in May 2002 in Mailsi in Punjab. Asif Ramzi, a Lashkar-e-Jhangvi operative wanted in 87 cases, was killed in December 2002. He was said to have links to the kidnappers of American journalist Daniel Pearl, who was later killed by suspected Al Qaeda operatives.

Many theories emerged on the killings―the war on terror, internecine clashes, harbouring hordes of extremists becoming untenable for the Pak spy agency Inter-Services Intelligence―but the perpetrators were never caught. Terrorism, however, bounced back. On the run, many militants joined hands with terror groups sitting across in Jammu and Kashmir where outfits like the Jaish-e-Mohammed and the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen used their skills to multiply their cadre.

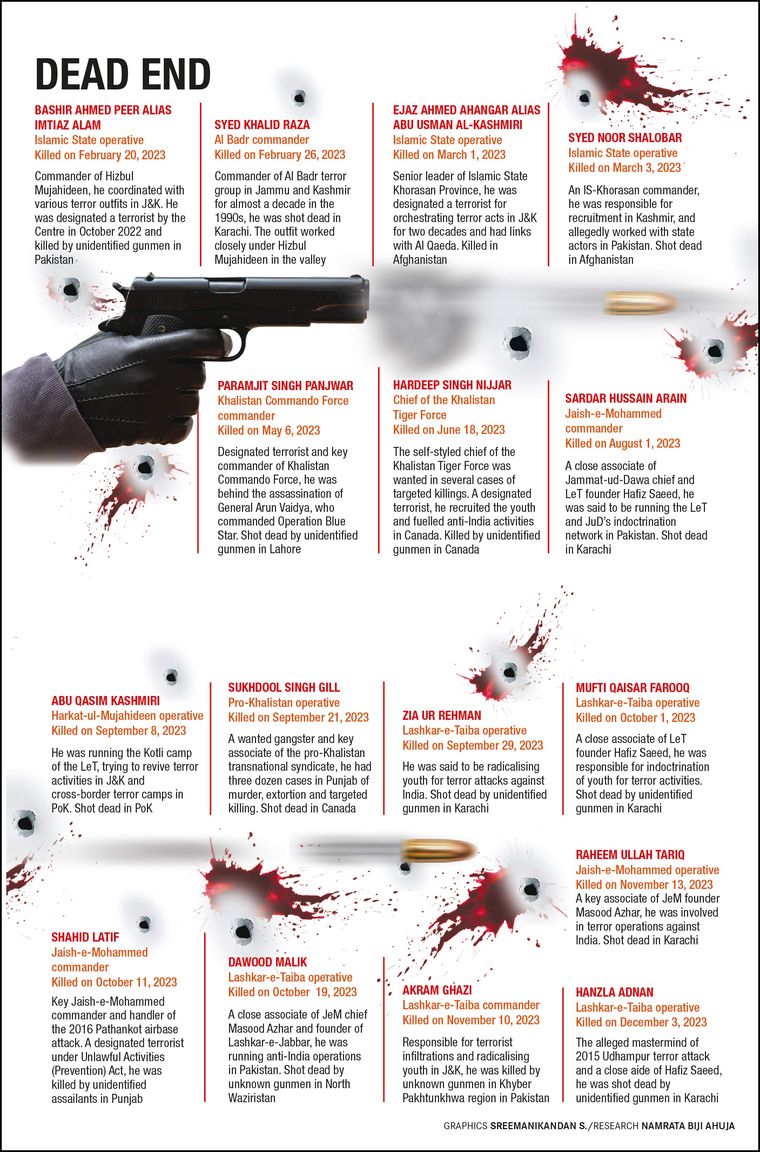

Now, two decades later, another spate of killings of extremists by unknown assailants brings the focus back on Pakistan. This time the targets were men “wanted” by India. Some of them were ideologues in their 70s―like Paramjit Singh Panjwar of the Khalistan Commando Force, who was gunned down on May 6―and some commanders running cross-border camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir or those who were active in the 1990s and early 2000s when terrorism was at its peak in Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab. Abu Qasim Kashmiri of Hizbul Mujahideen was killed by unknown assailants on September 8, 2023 and Shahid Latif of the Jaish-e-Mohammed was killed on October 11, 2023 in a commando-style operation. Latif was the handler of the 2016 Pathankot airbase attack, while Kashmiri was close to Hafiz Saeed, co-founder of the Lashkar-e-Taiba and the mastermind of 26/11 terror attacks in Mumbai.

Terror networks seldom protect their own, as they work on the principle of deniability. Hanzla Adnan of the Lashkar-e-Taiba, who was the mastermind of Udhampur terror attack in 2015 and considered close to Saeed, was rendered unfit for future operations after his voice samples and connections in Pakistan leaked to Indian agencies and the Interpol put him on its wanted list. He was killed by unidentified gunmen in Karachi on December 3.

Ashok K. Behuria, security expert at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, Delhi, said the killings in Pakistan 20 years ago were different from those happening now as Islamabad was then trying to show the Americans that it did not support terror. “The ISI did not want to be seen providing state support to extremists,” said Behuria. The situation is different now. While the killings made some headlines at that time, this time the Pak vernacular media is more or less ignoring it. “This may mean that Pakistan does not think too much of it,” said Behuria. “It will be difficult to say if those being killed lost their utility for the ISI, but these killings are certainly not their primary worry.”

While these killings are definitely a relief for India, it is too early to put the guard down. “The recent fatalities in terrorist groups, whether it is the Lashkar-e-Taiba or the pro-Khalistani terrorist groups, indicate that many have fallen to disuse for the ISI after the terror graph has gone down,” said Tilak Devasher, member of the National Security Advisory Board. “But many of them are medium level commanders or footsoldiers. The big ones are still in safe havens in Pakistan. The Pakistan-sponsored terror is pretty much alive and trying to revive its cross-border networks in Jammu and Kashmir.”

At the moment, the primary worry for the Pakistani security establishment is the “opportunistic partnership” between the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Baloch rebels. There is a growing suspicion that the TTP is getting covert support of the Balochs in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and other northwestern tribal areas, especially after Pakistan started fencing its border with Afghanistan. The ingress of TTP terrorists to Baloch areas is particularly worrisome for the Pakistani army because the country’s defence budget has not been rising in tandem with its growing need for new technologies and weapons owing to a troubled economy.

“On the other hand, the Indian defence budget has grown and its technological prowess and superiority overshadows Pakistan’s capabilities,” said Behuria. “If this trend persists, then Pakistan is likely to face newer challenges and problems.”

This, however, might be a temporary situation. “It is already on the mend,” said Behuria. “Friendly countries are helping it recover financially, the political dispensation has changed and Pakistani forces know how to sow seeds of discord within the TTP and Balochs.” Also the TTP, a conglomerate of various outfits, is no longer united. Indian security agencies believe that Pakistan’s attention will soon turn back to Kashmir and it will start training and funding terror activities there.

That Pakistan-sponsored terrorists have been able to build transnational syndicates stretching from Canada to Nepal is proof of its ability to continue its anti-India campaign. Almost all terrorists wanted by Indian security agencies have a Pak origin or connection.

Hardeep Singh Nijjar, the chief of the banned Khalistan Tiger Force who was killed by unidentified gunmen in Canada on June 18, was a key link to the Pak-sponsored pro-Khalistan network that orchestrated the assassination of former Punjab chief minister Beant Singh in 1995. In April 2012, Nijjar was in Pakistan, as per intelligence records, and he was groomed by the ISI to train terror operatives of the KTF in Canada to carry out operations in Punjab. He was subsequently linked to several acts of terror, including assassinations.

Lakhbir Singh Rode, head of the banned International Sikh Youth Federation and Khalistan Liberation Force, had a free run in Pakistan till he died of a heart attack on December 4. He lived in a safe house there and assisted Canada-based gangsters in terrorist acts, including the rocket-propelled grenade attack in Mohali in 2022. Jasbir Rode, his brother who lives in Punjab, told THE WEEK that his family in Canada informed him about Lakhbir’s death in Pakistan. The National Investigation Agency also has collected evidence of Lakhbir getting help from cross-border smugglers to drop weapons and drugs using drones in Punjab.

Yashovardhan Azad, former special director of the Intelligence Bureau, said whether it was Nijjar’s killing or the poisoning of LeT commander Sajid Mir, an accused in the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks, in Pakistan, the reasons were at best speculations. He said the internecine wars of terror-criminal networks were a rising threat for many countries. “Pro-Khalistani terrorists cannot tear the social fabric of Punjab as there is no sentiment for Khalistan in Punjab,” he said. “But these extremists can surely be a security concern for the host countries.”

The face of terror is changing―from ideologues to criminals running transnational syndicates. Azad said there was a need for the criminal justice system to evolve to keep pace with such threats. The US, for instance, has the PATRIOT Act that enables its law enforcement agencies to use certain tools to improve counter-terror efforts. It allows federal agents to take measures like surveillance and imposing tough penalties on those who commit and support terrorist operations.

“The ability to implement [rules] also matters,” said Azad. “Even if we have similar laws, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to execute it. The criminal justice system is still overburdened with long pendency of cases in courts.”

The US also has a federal witness protection programme and a provision for plea bargain. Pakistani-American terrorist David Coleman Headley pleaded guilty and admitted to conducting surveillance for the LeT in planning the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks. “In light of Headley’s past cooperation and expected future cooperation”, the attorney general authorised the US attorney in Chicago not to seek the death penalty for him in 2010. As a result, Indian agencies could not get Headley extradited.

From 9/11 to 26/11 and beyond, a lot has changed, but clearly there is a lot more to improve in the joint war against terrorism, which has neither boundaries nor laws.