When discussions on the Uniform Civil Code started at the Constituent Assembly, it ignited an emotionally charged beginning. The assembly saw some of its most heated arguments on November 23, 1948, the day it debated and approved the placing of the UCC under the Directive Principles of the Constitution.

The Directive Principles were being discussed that day, and Article 35, which dealt with the UCC, was pushed back to the end of the list so that it could be discussed at length. The debate saw impassioned arguments being made both for and against having the UCC. The members who were against the UCC―many of them from the Muslim community―argued that personal laws were distinct from other categories of law because they were part of the tradition, culture, customs and religion of different communities. It would interfere with the freedom to practise religion, and would, instead of promoting harmony, sow the seeds of disunity.

A member pointed out that he and some others in the assembly had received pamphlets from both Muslim and Hindu groups who felt that any interference with their personal laws was “most tyrannous”. It was asked whether it was possible in a country as vast and diverse as India to have a common set of family laws for all. There was also discussion on whether the term UCC covered the wider ambit of civil laws in the country and not strictly the personal laws.

Those who defended the UCC spoke about the need to dissociate laws from religious practices, saying the idea of personal law being a part of religion was perpetuated by the British. They said gender discrimination was common in these laws. And it was emphasised that a common civil law would help the cause of unity. Wrapping up the debate, B.R. Ambedkar, who headed the drafting committee of the Constitution, pointed out that the only province the civil law had not been able to invade so far was marriage and succession. “It is this little corner which we have not been able to invade so far.”

In the end, Article 35 was adopted, and it became Article 44 in the final form of the Constitution. It read: “The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a Uniform Civil Code throughout the territory of India.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

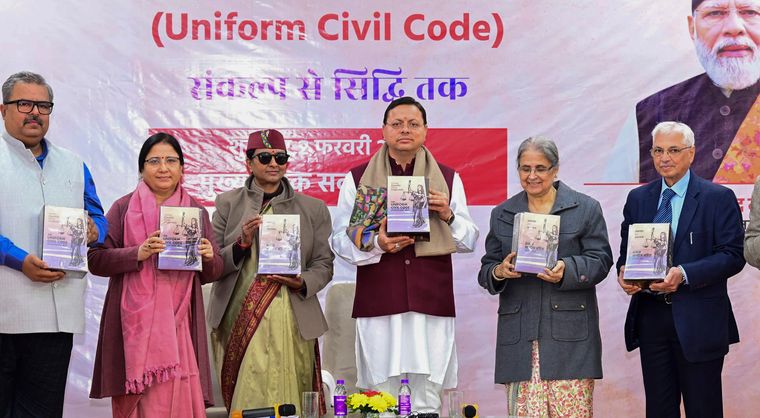

The UCC continues to be a contentious issue 75 years later, and the current debate is taking place against the backdrop of the process to enact the law for the first time. The BJP-ruled Uttarakhand is all set to become the first state since independence to enact it. (Goa has a version of the civil code that follows the Portuguese Civil Code of 1867.) Uttarakhand Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami tabled the UCC bill in the assembly on February 6 during a special session of the house. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s public declaration of support for the UCC is an assertion of the political intent of the ruling dispensation to put in place a common set of family laws for all citizens.

The term Uniform Civil Code is understood to mean a common set of civil laws for all citizens. What is not common at present, and what is sought to be made common are family laws governing marriage, divorce, maintenance, adoption, succession and inheritance. The founding fathers of the Constitution had more than an inkling of the difficulty of the task, hence the decision to not place UCC under the Fundamental Rights section of the Constitution. They chose to keep it under the Directive Principles, which do not make it mandatory for the state to bring in the UCC, but endeavour to secure it for its citizens.

The prime minister has said that India cannot run with a system of separate laws for separate communities. He gave the allegory of a family, and asked how that household could function well if the family members were governed by different laws. “Tell me, if in one house, there is one law for one family member and another one for another family member, can that house function?” he asked.

But a counter-question is posed by experts who refer to the diversity in law-making in the country that has been given legal protection by the Constitution itself. Parliament and state assemblies are empowered to make laws. There are subjects on which only Parliament can legislate or subjects on which only the states can make laws, and there is a concurrent list of subjects on which both Parliament and states can frame laws. Then, there are areas under the fifth and sixth schedules of the Constitution (covering tribal areas in several states) where laws enacted by Parliament and the state assemblies can be stopped from being applied and customary laws have been given legal protection under the Constitution.

“Uniformity is not homogeneity. The Constitution respects the plurality of the country. It also acknowledges and protects the diversity of law-making in the country,” said M.P. Raju, Supreme Court advocate and an expert on the subject.

Besides the need for all citizens to be governed by the same set of laws, the government says it is necessary for maintaining unity. But such an exercise could end up creating fissures and encouraging disaffection among different communities, according to its critics. This concern was emphasised by the 21st Law Commission in its consultation paper on the UCC, which came out on August 31, 2018.

The view that the UCC means a common set of family laws getting enacted and abolishing the diverse laws is deeply concerning and even a fearsome idea for most communities. And there have been strong reactions, from the Muslims, who are the largest minority, to the tribal groups in different parts of the country who fear that their unique customary laws are endangered. In its response to the Law Commission, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board has said, “Majoritarian morality must not supersede personal law, religious freedom and minority rights in the name of a code which remains an enigma.”

The Muslims, in particular, are viewing the UCC effort an attempt to evoke communally polarising sentiments ahead of the election season. “Why is the government insisting on the UCC? For the last 75 years, no government has been able to bring in the UCC for a reason. Nobody could even come up with a draft of the UCC,” said Saleem Engineer, vice president, Jamaat-e-Islami Hind.

The difficulty of reconciling the differences that exist between the personal laws has to be taken into account. For example, in Hindu law, marriage is a holy union; for Christians, it is a sacrament; for Muslims, it is a contract; and for Parsis the registration of the marriage is the central element of the wedding ceremony. The Catholic church does not permit divorce for valid sacramental marriages, while the Parsis have a jury system to decide on divorce. But the jury sits only twice a year, and this has been challenged before the Supreme Court. Again, the personal laws of Muslims, Christians and Parsis do not allow adoption, but for different reasons that emerge from their religious beliefs. The norms for inheritance and succession are also different for the different communities.

The response to the UCC debate by the Parsi community―one of the most prosperous communities in the country, but also one of the smallest numerically―provides an insight into the difficulty of the task of framing a common code of laws for all communities. The Bombay Parsi Panchayat had formed a committee of community leaders and prominent Parsi lawyers to frame a response to the Law Commission’s invite for suggestions. A formal meeting of the committee was held, and a sizeable section, in fact, spoke in favour of total exemption of Parsis from the UCC.

“We are worried about protecting our traditions, our unique religious practice, culture and ethnic identity. We are an extremely small community. The concerns are especially with regard to two subjects―adoption and inheritance,” said Kersi K. Deboo, vice chairman, National Commission for Minorities. The reason why adoption is not allowed in Parsis is because conversion is not permitted; that is, a child belonging to another community cannot become a member of the community. There is a strong emphasis on maintaining the purity of Parsi blood. While adoption is not allowed, under the ‘Palak’ system, a widow of a childless Parsi can adopt a child on the fourth day of her husband’s death only for the purpose of performing religious ceremonies. With regard to inheritance, when a male Parsi dies, his parents also receive a share in the property, along with his widow and children.

According to a senior official at the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India, after a vigorous discussion, the CBCI informed the Law Commission that the UCC was not required at this stage, and that efforts should instead be made to remove errors and discrepancies in various personal laws, especially with regard to gender discrimination, without destroying them. The bishops were also worried about the norms governing marriage, divorce, inheritance and adoption under the UCC.

The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, too, has rejected the proposal for the UCC, saying it threatens the identity of minorities. “Sikh identity and dignity and the Sikh code of conduct cannot be defined by worldly laws. It is derived from Gurbani, from the thoughts and teachings that are part of the Guru Granth Sahib,” said SGPC president Harjinder Singh Dhami. As of now, the only personal law that is exclusively Sikh is the Anand Karaj Act for registering Sikh marriages. With regard to other family laws, Sikhs are governed by Hindu laws.

Experts feel that there is a lot of traditional common sense in customary laws that could be sacrificed for the sake of UCC. For example, among the Garo and Khasi tribes of Meghalaya, the youngest daughter inherits the property. The reason for this is that elderly parents can rely upon their youngest daughter for care in their sunset years. Meanwhile, it is also being asked if a common set of laws will see the removal of coparcenary (joint heir) system of inheritance for Hindus, which is viewed as being discriminatory towards women, or the abolition of the Hindu Undivided Family norm.

With regard to the claim that one of the aims of bringing in the UCC is to provide gender justice, it is argued that reforms in individual laws could be carried out, as has happened in the past, rather than try and have an omnibus set of laws for the entire country. “The command of the Constitution is that if there are anti-women family laws, they are unconstitutional and will have to be removed or amended. That has been happening, through legislations and through judgments of the constitutional courts,” said Raju.

The previous Law Commission, too, had suggested a range of amendments to the existing family laws to deal with bias against women and also recommended codification of certain aspects of personal laws to limit ambiguity in interpretation and application of the laws.

The little corner, which Ambedkar said could not be invaded by common civil law, continues to be a tough terrain to conquer.