IN MARCH 2016, less than two years into his first term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi told his party’s office bearers that he preferred having simultaneous elections to the Lok Sabha and state assemblies. At the time, not many thought it was possible. Eight years later, the Centre believes it is an idea whose time has come.

The concept, on the surface, appears appealing, with the government saying it is necessary to curb excessive spending, eliminate the perpetual election cycle and redirect focus towards governance. Critics, however, argue that it could homogenise India’s political diversity and diminish regional concerns.

Former president Ram Nath Kovind’s report on ‘One Nation, One Election’ (ONOE)―submitted just two days before the 2024 Lok Sabha election dates were announced―will give the BJP a topical campaign issue. Voters would be more receptive to the idea while they see the crores being spent around them.

For the BJP, fulfilling promises such as the Ram Mandir, abrogation of Article 370, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and ONOE has been a priority. In fact, Modi’s second term has been better than his first in terms of fulfilling ideological promises.

And with the aim of winning more than 400 seats this time, the Modi government might pursue further transformative measures, beginning with ONOE. “Certainty is important for decisions central to good governance, which leads to faster development,” said the Kovind report. “On the other hand, uncertainty invariably leads to policy paralysis... [the simultaneous polls] will significantly enhance transparency, inclusivity, ease and confidence of the voters.”

If elected to power, the Modi government intends to amend the Constitution in its first Parliament session to bring the plan to life. Once implemented, ONOE has the power to transform the political and governance patterns in the country.

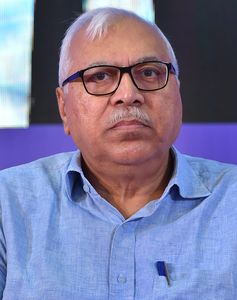

But not everyone is impressed. Opposition parties and some experts say the idea is against the federal structure and might do more harm than good. “The whole proposal lacks sincerity,” said former chief election commissioner S.Y. Quraishi. “If the idea is to curb staggered elections as a lot of money is spent and governance is stalled, why have a prolonged general election (2024) that stretches over three months? This time it is longer than ever before. Previously, we had Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh going to the polls at the same time, but the last two times they were held separately. If [ONOE] is good, why were the elections that took place simultaneously segregated?”

The Kovind committee received views of 47 political parties, of which 15, including the Congress, the left parties and the Trinamool, opposed the idea. The panel had suggested a simple formula―in the first phase of these election reforms, simultaneous elections would be held for the Lok Sabha and state assemblies. For this, constitutional amendments need to be made, but the BJP, which has the numbers in Parliament, would not find this hard to do. The panel has recommended that half of the state assemblies need not ratify the amendments.

In the second step, elections to the municipalities and the panchayats will be synchronised with the Lok Sabha and state assemblies so that these elections can be held within 100 days of the main election. Here, 50 per cent of the state assemblies need to ratify it. The BJP is already in power in 12 states, and rules in a coalition in five others. That takes it to beyond half.

The tedious part of the process, given the volatility of Indian elections, is what will happen if there is a hung house, a no-confidence motion or withdrawal of support. The panel proposed that fresh elections be held to constitute the new Lok Sabha or assembly for the “unexpired term” of the house. Those polls will be called mid-term elections.

Quraishi said this could lead to more elections within five years. For instance, if a government falls with one year of its term left, fresh elections will have to be held for a term of only 12 months. “Are we reducing elections or increasing them? It is a pointless kind of recommendation,” he said. “Just because it is from a high-powered committee does not make it a high-value recommendation.”

Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge, in his submission to the panel, argued that the claim of higher costs was baseless as the expenditure in 2014 (Rs3,870 crore) was less than 0.02 percent of the previous budget, which is not a lot of money compared with the damage that could be done to free and fair elections. “In the past 10 years, the only instances where the chief ministers have lost the confidence of the house have been when one particular party has abused the government machinery and subverted the anti-defection law to steal the people’s mandate,” argued Kharge. “The government, Parliament and the Election Commission should work together to ensure the people’s mandate is respected rather than divert people’s attention by talking about undemocratic ideas like simultaneous elections.”

Another crucial aspect would be the preparation of a single electoral roll and electors photo identity cards (EPIC) for use in elections to all three tiers of government.

As for the legislative challenges, the tenures of several states would have to be curtailed or extended to hold simultaneous polls. This is likely to cause dissent among opposition-ruled states.

However, the bigger challenge would be for the election commissions, Central and state, in terms of logistics. Consider this: during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, there were more than 10,38,000 polling stations, for which 70 lakh polling personnel and staff were deployed, and 3,146 companies of Central and state armed police forces were used, which was 30 per cent more than in 2014. For the upcoming elections, 4,719 companies will be needed. And so on.

The next big challenge would be the electronic voting machines. As per the ECI, if simultaneous elections were to be held in 2024, the shortfall would be 15.97 lakh ballot units, 11.49 lakh control units and 12.36 lakh VVPAT (Voter-Verified Paper Audit Trail) units. The total additional cost, at 2024 prices, would be more than Rs5,190 crore. The cost will rise significantly as the number of booths, especially after delimitation, would be much higher.

The ECI estimated that there will be more than 13.57 lakh polling stations in 2029, when the simultaneous elections are expected. The cost to overcome the shortfall in ballot units, control units and VVPATs would be more than Rs7,951 crore. Given the problems in the chip industry, among other issues, the ECI would need sufficient time and planning to fill the gaps. Additionally, the ECI needs warehouses, staff and technicians for the upkeep of EVMs.

Even as the logistical issues persist and the opposition steps up its demands, the BJP argues that this is not a new idea. “Simultaneous polls existed in Bharat till 1967,” said BJP spokesperson and lawyer Nalin Kohli. “It was the politics of Indira Gandhi that brought about the break as many state governments were sacked. ONOE will result in an uninterrupted governance period, which can only be to the benefit of the people.”

The panel report also talks about the phenomenon of ‘voter fatigue’, which is characterised by apathy and disinterest among voters because of the recurrence of elections.

Smaller parties and states, however, fear that their unique concerns and ideas might get overshadowed by the national parties. Moreover, having elections only once in five years could reduce the government’s accountability.

To that point, ONOE might find more resonance in the Hindi heartland, where the BJP is in power, than in the east or south, where regional parties dominate.

Kohli, however, disagreed that ONOE would hamper regional sentiment and was against the federal spirit. “Data do not speak in that direction,” he said. “The people of India have voted for separate political parties during simultaneous polls. A consistent example of this is Odisha.”