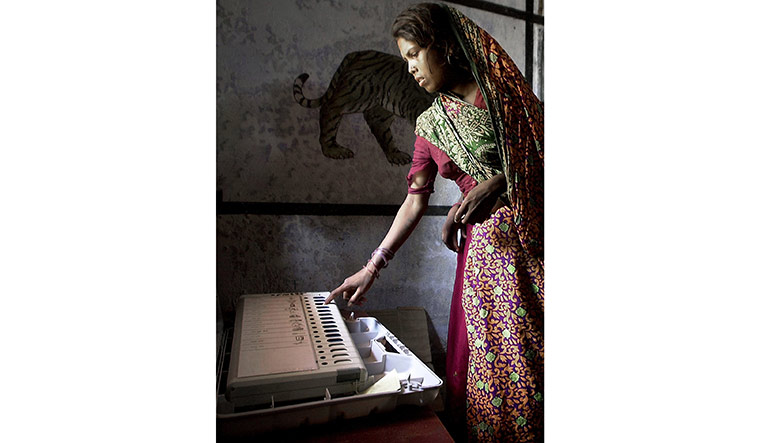

Although the electronic voting machines were first introduced at the national level for parliamentary elections in 2004, the steps for introducing such a device were taken several years before. We had the conventional ballot paper voting, which is in vogue in many countries even now. The Election Commission replaced the ballot paper system because of its inherent infirmities.

Broadly, EVMs prevent manipulations in the ballot paper system, including booth captures. They also eliminated invalid votes and helped save paper and time. EVMs are manufactured by Bharat Electronics Limited and the Electronics Corporation of India Limited, both public sector undertakings, as against the experiment conducted in the US where the EVMs were manufactured by a private company. This is a very important difference.

When I took over as chief election commissioner in February 2004, the commission had to decide on using EVMs on the basis of the experience gained from the (initial) use of the machines in some Assembly elections and byelections. The decision to implement the use of EVMs in about eight lakh polling stations was based on the report of an expert committee headed by DRDO technical expert S. Sampath. When the machines were tried in some Assembly polls and byelections, voters uniformly welcomed the change. This was, however, different from the response of some political parties, which questioned the credibility of the machines. It is significant to note that the Supreme Court had also cleared the use of EVMs after some petitions were filed challenging its use. The two political parties that had challenged the use of the machines came to power through the use of these very machines in the subsequent elections.

We had to take certain administrative actions to make a shift to EVMs. We had to get more than five lakh machines ready as the existing stock was only 50 per cent of the overall need. We had to request the two PSUs to increase the rate of production of these machines and provide the EVMs in about four to five months. Added to this, to make funds available for smooth production, I wrote a letter to then prime minister (Atal Bihari Vajpayee) for allocating extra funds on a priority basis as the financial year was coming to a close. Fortunately, we got the funds allocated, and the PSUs did a remarkable job in getting the machines ready on time. The next challenge was to administratively make the machines accessible to voters and political parties. We had to train a large number of polling personnel to take EVMs to various nooks and corners, and demonstrate their use and convince the people about their credibility. The Election Commission prepared manuals in time to reach various district election officers for education and training of polling personnel. Apart from court litigations, some political parties campaigned against EVMs and one of them even stated that the machines could give an electric shock if not properly used.

We had a mock poll at each polling station before the commencement of voting in the presence of polling agents, representing contesting candidates, and got their assent about the correctness of the machines. So it would be unfair to say that the machines could be manipulated or interfered by a remote system.

On the day the election results came out, a TV channel asked me whether I was nervous about the outcome of the election conducted using EVMs. My reply was an emphatic ‘No’ as we found that the mammoth job of propagating the use of the EVMs was very well done by the officials from state governments as well as the Central government. I would also like to add as the election was on for nearly five weeks in 2004, we had lined up officers and reserve machines for all the polling stations in case there was any complaint.

I am happy to say that the number of complaints during the entire election process was less than 1 per cent, and we found later that the machines which were subsequently replaced were not properly used by the polling officials or the voters. Even when there were complaints against the machines when the voting was taking place, we immediately replaced them with new machines to convince the voters that there cannot be any manipulation. I can also add that there was no election petition questioning any irregularity in the use of EVMs, although there were other petitions filed for different reasons.

The introduction of EVMs was financially justifiable as the cost of machines was not more than that of manufacturing ballot boxes and printing of ballot papers. Most importantly, the machines ensured timely conduct of an election in which almost 60 crore voters participated and timely declaration of its results. It may be relevant to note that in a country like Indonesia, the declaration of results takes more than three to four weeks, whereas we are able to announce the results within 12 hours of the start of the counting.

To remove the apprehension of political parties, there is still a demand for 100 per cent matching of votes with the VVPAT system―introduced much later―even though the Supreme Court had in its order said VVPAT slips be counted in five randomly selected polling stations per assembly constituency.

I have no doubts about the credibility of the machines and I also consider it a matter of the nation’s pride that this change was brought about and we improved our electoral system. Though very often the losing parties/candidates blame the machines, my answer is that the machines cannot lie, only humans can. With the kind of safeguards available in the machines, it can be seen that in many states the ruling party is losing the election and new parties are coming to power. While in one state a particular party may lose, the same party can win in another state. This is more than adequate proof of the credibility of EVMs. If the political parties want some change even now, they should look for improvement in the existing system rather than reverting to the conventional ballot system, which was manipulated and misused by many parties. One ample proof of its misuse is the recent mayoral election in Chandigarh where ballot papers were made invalid and the Supreme Court had to intervene to set matters right.

―As told to Soni Mishra