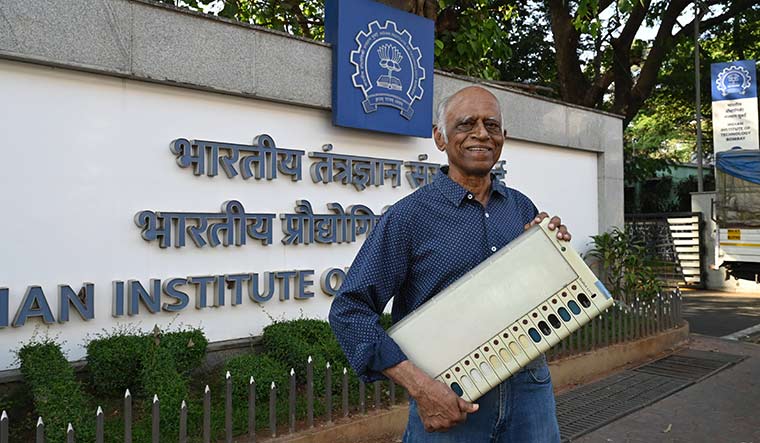

In early 1988, a small team of designers with an engineering background embarked on an ambitious project at IIT Bombay’s Industrial Design Centre (IDC). The team was asked to design an electronic voting machine (EVM) that would replace the conventional ballot system. The result: the EVM as we know it now.

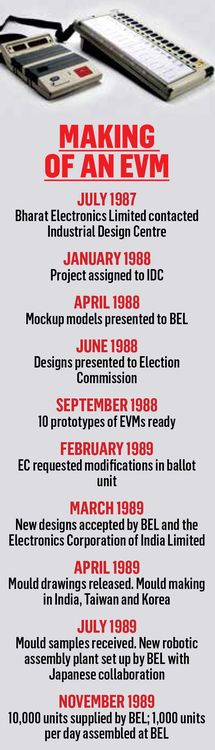

The IDC had to design the EVM, from concept to the final prototype, based on the electronic design done by Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL). The Election Commission had entrusted the task of developing EVMs to BEL and the Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL), both public sector undertakings. ECIL had, meanwhile, asked the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, to submit design proposals for the EVM. An earlier version of the EVMs was used on a trial basis in some booths in the 1982 Kerala assembly polls.

For a year and a half, the team at IDC worked on the design of a machine that would transform the way elections were conducted in the country. The team, led by Prof A.G. Rao, spent many nights in the IDC lab brainstorming for innovative solutions. The team found inspiration in the traditional ballot system, which they strove to capture in the EVM―the elliptical button that the voter presses on the EVM to cast a vote resembles a voter’s thumb impression.

The design team visited polling booths during the Andhra Pradesh bypolls held the same year to study the conditions in polling stations and to capture the user experience. “Our effort was to design an EVM that was in keeping with the Indian conditions,” said Rao. “It involved use of sturdy materials like engineering plastics, ensuring ease of setting up the machine before voting because officials and teachers who have no technical background would be operating it and highlighting tamper-proof details. Also, the colour scheme had to be neutral and non-controversial.”

Added to this, Rao said the machine had to have no connections to a central computer to eliminate chances of manipulation. The memory is stored in the control units, which are brought physically to a central place for counting and opened in front of all political parties.

To assuage any concerns about tampering, a provision was made to top the electronic sealing of the EVM with the traditional ‘lac’ sealing wax that was used by polling officials to seal the ballot boxes. It was important to give a physical aspect to the security of the EVM so that it was visible to the people and to political parties.

Prof Ravi Poovaiah, who was also part of the IDC team that designed the EVM, said, “One of the main priorities was to use cost-effective solutions in terms of materials and technology. We looked for indigenous solutions, be it the mould making of the machine or the carry case or providing plastic hinges in place of metal hinges on the machine, which, in the long run, saved a lot of money and time in manufacturing.”

A challenge the team faced was to convince bureaucrats. At the time of the presentation of the mockup of the EVM before the Election Commission, Rao had dropped the prototype of a telephone, which he had designed for C-DOT, made out of engineering plastic from a height of eight feet to demonstrate its durability. But an official who dealt with finance pointed out that he had dropped it on a carpeted surface. In response, Rao said he was ready to drop it from the second floor onto the concrete basement below and the official could go and check if the machine was fine after the fall. This silenced the official, who had also asked why the unit would cost so much. He had to be told it was not a suitcase, but a computer.

Both Rao and Poovaiah emphasise the safety and reliability of the EVM. Reacting to doubts expressed by certain parties that the machine can be manipulated in a way that no matter which button you press, the vote will go to a certain party, Rao said the sequence of the names on each ballot unit is done in alphabetical order and not in the order of political parties. “So the sequence of names changes accordingly,” he said. “It will be different in each constituency. The same EVMs are used in all constituencies, and the same mass-produced read only memory (ROM) printed circuit board is used in each machine. In my view, the present technologies may be inadequate to change the ROM pieces from outside.”

According to Poovaiah, what makes the EVM secure and reliable is that it is a standalone machine that is not linked to any other gadgets and one cannot get into the system even by using Wi-Fi. “The electronics of the EVM is very simple,” he said. “It can only do number crunching, which serves the purpose of keeping a tally of votes. To tamper with this is impossible. It is totally foolproof.”

The team had to race against time to finalise the design so that it could be ready for manufacture and use during the 1989 Lok Sabha elections. In March 1989, the final design of the EVM was accepted by both BEL and ECIL. In July, BEL set up a new robotic assembly plant with Japanese collaboration for Rs10 crore, and by November, the company had supplied 10,000 units. The EVMs cost Rs5,000 per unit.

The Rajiv Gandhi government passed a Constitutional amendment in March 1989 to enable the use of EVMs. Before that, a proposal to use EVMs in elections was revived in the government in 1986-87. In 1982, some EVMs provided by BEL, based on the machines that the company had used for its in-house purposes, were used in some state assembly elections on a trial basis.

However, the EVMs were not used in the Lok Sabha elections in 1989 because of lack of political consensus. The EVMs were put on the backburner, and could finally see the light of the day in 1998, when it was used in some assembly elections.

“We felt it would not take off,” said Poovaiah. “Finally, it did. It has been hugely successful and there is little change in the design.”