Mindo, 52, points to her rebuilt verandah, a stark reminder of the floods that damaged her house in Sultanpur Lodhi’s Mandala village last year. As she offers a charpoy and a cup of tea―the warm Punjabi welcome―she recalls how water engulfed her house, even breaching the metre-high porch. “It was a nightmare,” she says. Her son Haroon, who runs a grocery shop to supplement the income from farming, nods in agreement. “We had to borrow money to rebuild, with no help from the government,” he says. Nearby, labourer Santosh Singh, 28, is still repaying the hefty loan he took to reconstruct portions of his flooded home.

The situation is no different in Talwara, about 90km from Sultanpur Lodhi. Says Jigir Singh, a rice farmer from Tadhe Pind: “My farms, spread over 12 acres, were submerged, and the crops completely destroyed.” The 55-year-old remembers seeing such floods more than 40 years ago, indicating changes in the monsoon pattern. Thousands of villages in more than 24 districts in Punjab bore the brunt of the fury of the Sutlej and the Beas; nearly 50 people died.

While in the north, the Bhakra Nangal and the Pong dams overflowed to wreak havoc downstream, the sudden gush of water from Kerala’s Idukki dam in 2018 also pointed to, as the local people put it, a major shift in rainfall. C.J. Stephen, 48, representative of the merchants’ association in Chappath on the banks of the Periyar, says that normally, even if water was released from the Idukki Dam, it would take three hours to reach Chappath. “But that day, the Idukki collector instructed us to immediately relocate products kept in our shops,” he recalls. “We informed the shop owners, but not many took the warning seriously. By evening, water from both the rains and the dam release flooded the village. Many merchants had stocked up in advance for the Onam season. They lost everything.”

In the east, the River Teesta, once said to be benign, is now seen as dangerous. The turning point came last October when a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) from South Lhonak Lake unleashed chaos at the Chungthang 1,200MW Teesta 3 hydropower project in Sikkim, killing 42 people and impacting 88,000 others across the Teesta basin. This unexpected disaster sparked critical conversations about the management and sustainability of hydropower projects across India. “We have been living in a rental home since the GLOF occurred. My house was completely damaged,” says Lakshmi Lama, 52, a resident of Teesta Bazar in West Bengal’s Kalimpong district. “The local administration gave us rent for six months. But now we are on our own. We want our home back.” People claim that the hydropower projects ignore the widespread destruction caused by incidents like the GLOF in Sikkim. “These hydro projects have killed the Teesta river. It now normally flows at the danger level. Thus, when it rains, the water comes to our doorstep,” says Suren Lohar, Lama’s neighbour. “The project authorities have failed to manage the river properly.”

The relationship between monsoons and dam management has always been tricky. Dams, or the “temples of modern India”, as former prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru called them, help with flood control, hydropower generation and storing water for dry seasons. A major chunk of water from dams is used for irrigation. Monsoons, however, come with a degree of unpredictability. Despite tech-driven forecasts that help in saving lives and property, critical concerns related to dam safety are emerging because of climate change and increasingly errant rainfall patterns across the globe.

Says Suruchi Bhadwal, director, earth science and climate change, The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), “With climate change, there will be a greater number of extremes and higher precipitation in terms of rainfall, and this will certainly result in an increase in risk aspects of dams in many parts of the country.” As Archana Verma, mission director of National Water Mission, said at the annual sustainable water management conclave, “Unlike monsoon patterns in the European and western nations which are usually spread out, India gets 50 per cent of rains within 15 days and in less than 100 hours altogether in a year, which makes storing water a big challenge.”

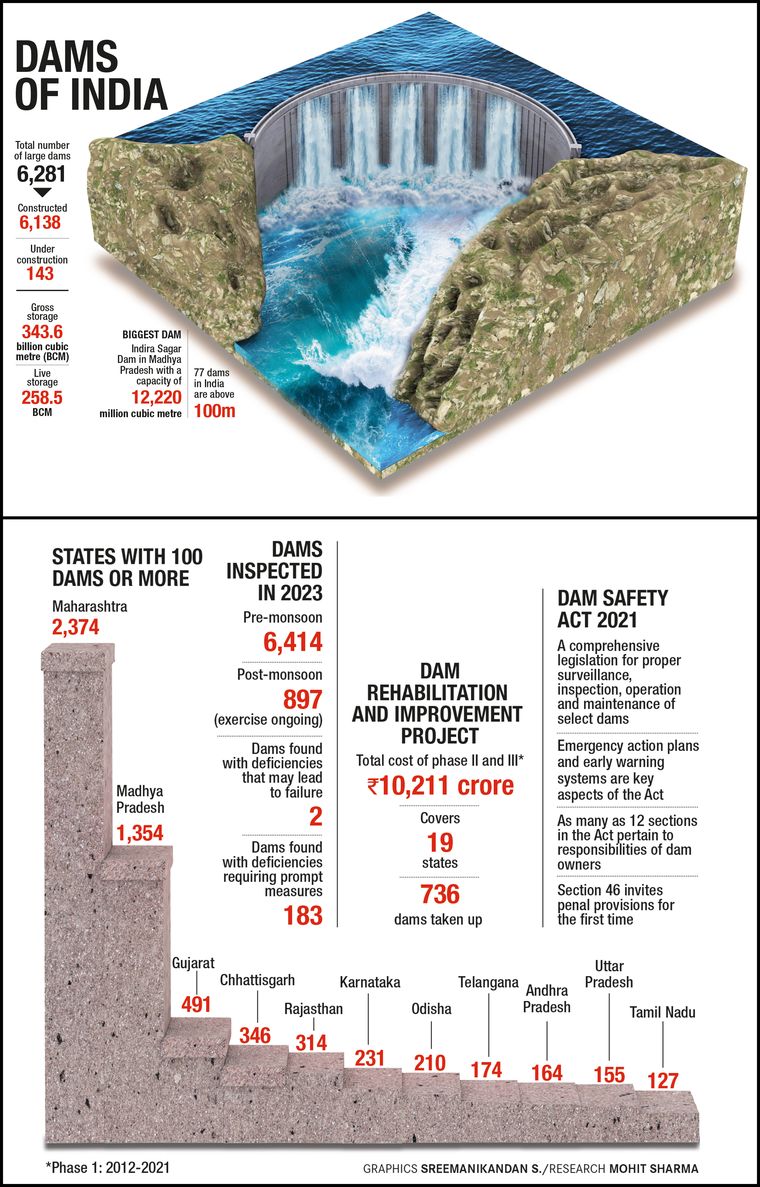

India, the third largest dam-owning nation in the world after China and the US, acknowledges the threat. As per the National Register of Large Dams 2023, India has 6,281 large dams, of which about 70 per cent are more than 25 years old, 1,034 are between 50 and 100 years old and 234 more than 100 years old. Recent inspections have found that two dams have defects that may lead to failure and 183 dams have defects that require immediate attention. While India’s dam safety standards are comparable to those of developed nations, there have been notable instances of unwarranted dam failures and inadequate maintenance.

In response to such instances, India passed the Dam Safety Act in 2021. It led to the formation of a National Committee on Dam Safety to oversee dam safety policies and regulations, a National Dam Safety Authority (NDSA) to look into implementation issues involving states, a State Committee on Dam Safety and State Dam Safety Organisation. The law also calls for comprehensive safety reviews of all dams by independent experts, besides making it compulsory for dam owners to take time-bound safety actions. More importantly, the act mandates emergency action plans and provisions for early warning system (EWS).

Former Union power minister R.K. Singh had admitted that the presence of an EWS could have allowed the Teesta dam’s gates to be opened in time, thereby minimising the damage. Just three months before the Sikkim tragedy, gates of Pong dam in Himachal Pradesh were blocked by boulders, leading to a sudden release of water, inundating areas downstream. Sources say that the dam, managed by the Bhakra and Beas Management Board, lacks hydrological stations to measure water levels.

The sudden release of water from the Sardar Sarovar dam last September is another case in point. A report by the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) states that despite advance information about rains upstream, water from the Narmada river was released at once, flooding the low-lying areas. The NDSA’s preliminary report also found that crucial time was lost in taking preparatory action. The opposition Congress in Gujarat attributed the floods to gross negligence by authorities overseeing the Sardar Sarovar Project. Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator of SANDRP, says that forecast is not unreliable every time. “There have been instances when appropriate action is not taken despite advance warning, and the Sardar Sarovar incident is a clear example,” he says.

An official at the Pong dam, however, pointed at the dilemma faced by the engineer who has to ensure the timely release of excess water to prevent floods, and also see to it that the dam is full by September 30, the last day of the monsoon. “His job is on the line if he is not able to perform either of the tasks,” he says. “And with uncertainty in rainfall and a lack of trust in forecast, this job has become even more difficult.”

Experts believe that the Dam Safety Act has the potential to plug such gaps. The World Bank, which is partly funding India’s ambitious Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Project (DRIP), has prepared a report on the increasing complexity between erratic rainfall patterns and dam safety. “The risks to dams are real and India is on the right path to address them,” says a World Bank official. With financial assistance from the World Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, India, under DRIP phase II and III, aims to rehabilitate 736 dams in 19 states with a budget outlay of Rs10,211 crore for 10 years.

However, sources say the pace at which early warning systems are being installed does not inspire confidence. Only 220 of 6,281 large dams have been equipped with EWS since the passage of the act. Also, concerns have been raised about the available manpower to implement the act. “Around 200 people from the Central Water Commission (CWC) have been given the additional charge of dam safety work. This shows the lack of manpower to undertake the mammoth task,” says a source.

Moreover, rule curves of dams need to be updated to avoid disasters, says Thakkar. Rule curves are target levels to be maintained in the reservoir during different periods of a year, under different conditions of inflows. Vijay Kumar, whose Jomiso Consulting Ltd designs EWS, seconds Thakkar’s point, adding that “there is also an urgent need for Integrated Reservoir Operation, which entails linking together of operations of all dams on any single river”.

After last year’s breach of Pong and Bhakra dams, a committee headed by the CWC was formed. Although its report is still awaited, the CWC shared a revised rule curve for Pong dam, besides approving eight sites in the catchment to strengthen hydrological observatory. The Central Electricity Authority has issued advanced standard operating procedures for installing EWS and listed 46 dams needing immediate attention.

Experts also underscore the ecological impacts associated with dam construction worldwide, leading to biodiversity loss, disruption of crucial ecosystem services and threats to local communities’ livelihoods. Referring to the damage caused in Sikkim, Subir Sarkar, retired professor of Geography in North Bengal University, says, “Lack of afforestation and unregulated construction in the catchment area are major factors for the situation Teesta has landed in.” Adds Praful Rao of Save The Hills, an NGO that works in disaster management in North Bengal and Sikkim, “Scientists from Hyderabad-based National Remote Sensing Centre had alerted the government on the high vulnerabilities of the South Lhonak lake for GLOF. However, the authorities turned a blind eye and the result is for everyone to see.”

It is that time of the year when fears of deluge loom large. The Teesta region has been on high alert as landslides wreak havoc. Viral landslide videos from the Himalayas trigger memories of the havoc unleashed in Manali last year. The Delhi deluge is still fresh in the minds of people. Areas downstream of Idukki and Mullaperiyar are also on alert. Stephen notes that Chappath has been the focal point of protests demanding the decommission of the Mullaperiyar dam. The reservoir, he says, is situated in a seismic zone and the region is extremely vulnerable to climate change. Fear grips Mindo every time she hears about rains in the hills. Sitting on her charpoy, she prays for the monsoons to pass without breaching her porch.

With Nirmal Jovial and Niladry Sarkar