SIACHEN

In the treacherous heights of the Siachen glacier―a vast, icy expanse where temperatures plummet below minus 40 degrees Celsius and avalanches loom with deadly intent―unsung heroes toil with unwavering courage. These porters, hailing from scenic villages in the Nubra valley, such as Kubed, Thang, Hunder, Turtuk, Tyakshi, Chalunka and Diskit, play a crucial role for the Army. Serving as guides, scouts and logistics managers, they venture into areas inaccessible to soldiers, fixing ropes for them to climb, acting as frontline responders to medical emergencies and providing crucial assistance in rescue and evacuations. Their knowledge of the terrain and experience with the harsh conditions make them indispensable in Siachen, located 22,000 feet above sea level. But their bravery and sacrifices often go unnoticed.

The Army moved into Siachen in 1984 under Operation Meghdoot to pre-empt Pakistan capturing the strategically significant area. Overcoming resistance from Pakistan, it secured critical peaks and passes such as Sia La (over 18,000ft), Bilafond La (over 17,000ft), and Gyong La (over 18,000ft), along with the commanding heights of the Saltoro Ridge on the southwest of the Siachen glacier. This allowed India to prevent intrusions not only by Pakistan, but also by China. Since then, the porters have been integral to the survival of soldiers at Siachen.

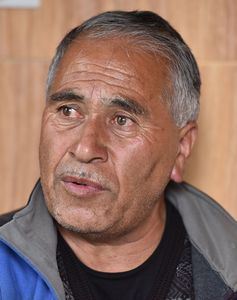

Lobzang Stobdan, a resident of Kubed, started working as a porter during Operation Meghdoot. “I was a teenager then. A porter was paid Rs1,500 a month,” he recalled. “That was a significant amount in those days and many men enlisted for the job.” He participated in reconnaissance and obstacle clearance. Acknowledging his accounting skills, the Army entrusted him with keeping records of porters. Following that, he coordinated with the Army to provide porters as needed. “The threat is extremely high,” he said. “To date, 26 local porters and five Nepali porters have lost their lives.” Getting caught in an avalanche or a crevasse causes hypothermia and hypoxia. Hypothermia impairs movement and cognition, leading to frostbite, cardiac arrest and coma, while hypoxia damages the central nervous system and organs. Falling into a crevasse also causes fractures and permanent incapacitation.

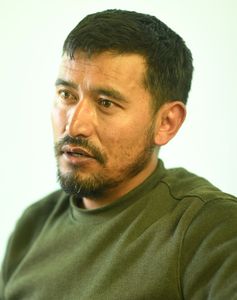

Stobdan’s role as a record keeper saved him from such hazards, but porters like Stanzin Padma, 35, have narrowly escaped death more than once. He took up the job in 2008 and received the Jeevan Raksha Pathak in 2014 for his services and exceptional bravery.

On January 12, 2012, during his posting at Sia La, Padma responded to a call from a post with dwindling food stocks. On his return, he lost his way because of poor visibility. His snow scooter got stuck in the snow, forcing him to walk. He plunged into a crevasse and, hours later, regained consciousness, finding himself trapped in a deep, icy chasm. “I had my wireless set with me and called for help,” he said. “I spent the night fighting sleep, hoping to be rescued in the morning.” At dawn, rescuers found his snow scooter, located him by his calls, and pulled him out with frostbite on his fingers. Luckily, he avoided amputation.

In December that year, his colleague Nima Norboo fell into a 200-foot-deep crevasse. After initial rescue efforts failed, Padma persuaded the commanding officer to arrange for a helicopter. He slid down into the crevasse with a rope from the helicopter, and saved him. “He survived, but lost an arm and both legs below the knee,” said Stobdan. “The Army compensated him and arranged for his livelihood.”

Padma’s most heroic moment was in May 2013 as part of a team that saved two soldiers buried under an avalanche at Tiger LP (21,500ft). They had to temporarily stop the rescue work because of another avalanche. They returned the following day and rescued the survivors. Unhappy with the remuneration and the lack of growth prospects, he quit working in Siachen and became a private contractor.

Rigzin Wangchuk, 41, from Chamshain, who has been working in Siachen for decades, recounts his own harrowing experience when he was buried under tonnes of snow while evacuating a sick soldier at Kaziranga Post, located at 19,000ft. Fellow porters managed to dig through the snow and save him from a painful death.

“When soldiers or porters move on the glacier, they tie themselves to each other using a long rope, leaving eight to ten feet of slack between each person,” he said. “That pinpointed the spot where I was buried.” He said the incident left him shaken. “I was gasping for breath under mounds of snow, thinking my end had come,” he said. “Fortunately, my colleagues retrieved me in time.”

He had a tryst with fate again in February 2016 when an avalanche struck the Sonam Post (19,500ft). Ten soldiers were in their sleeping bags when the tragedy struck. The recovery team at Kaziranga Post, where Wangchuk was on duty, set out for rescue, but what they saw left them shocked. “The post lay buried under an enormous chunk of snow several hundred feet long and wide that had cracked off from the mountain,” Wangchuk said. “The Army and the Air Force airlifted ice cutters, thermal imagers and doppler radars, part by part, to the site. After six days, one soldier, Lance Naik Hanumanthappa Koppad, was found alive, but was severely injured.” He was airlifted to the Army Hospital in Delhi, where he slipped into a coma, and died of multi-organ failure. “The news of his death saddened us a lot,” he said. “He had survived the worst, he deserved to live.”

Rinchan Namgyal, 41, who began working as a porter two decades ago, said weather was the main adversary at Siachen, especially in winter when the threat of avalanches was high. “Once we are deployed at the glacier, we remain there for three months,” he said. “We get the same clothing, shoes, food and medical support that the Army gets, but danger always lurks.”

Surviving a few near-death accidents seems to have toughened his resolve. “The most terrifying accident was when I fell into a crevasse 35-metres deep while riding a snow scooter,’’ he said. “I thought it was the end. But porters and soldiers pulled me out.”

Sonam Norbu, 25, opted to work as a porter after his efforts to find a job, including attempts to join the Army, were unsuccessful. He was listed as a porter for Siachen during Covid. He said he often wondered what life would be like up there, being cut off from the outside world for months. “After I signed up, I realised that Siachen was a far more dangerous place than I had imagined,” he said. “Death lurks everywhere, under the feet and over the head.” He said that except for taking the oath, porters did everything the Army did and remained deployed like the soldiers for three months. “I know I can lose my life, but it is more than a source of livelihood; it is an honour reserved for a few,” he said. “It is a rare chance to serve the country.”

He recalled an incident involving an Army officer who slipped into a crevasse. “The officer suddenly fell into a 45-metre crevasse,” he said. “One of the porters got him out within an hour. The officer suffered some fractures, but survived,” he said. “We carried him to the base camp, and from there, he was taken on a helicopter for further treatment.”

Stobdan said the soldiers were provided with world-class facilities. “This has reduced cases of medical emergencies to negligible numbers, but the weather continues to be a threat.” He said that before taking up their duties, porters, like soldiers, undergo acclimatisation at the Siachen base camp.

“Then they proceed with 20kg of load to the Kumar Post, a logistical base situated 15,600ft from the base camp. From Kumar, they ascend to altitudes between 21,000ft and 22,000ft. Travelling from one post to another takes three to four hours, with one person responsible for opening up the route. Once we deliver supplies to a post, we have to return to our post the same day. We eat and sleep at the post,” Padma said.

According to Stobdan, porters are employed for 89 days as casual paid labourers. A 90-day tenure without break entitles them to permanent employment and better pay. Porters are paid according to the grade of the post they are assigned to, with the grade determined by altitude and associated risks. “Those serving at higher altitudes receive Rs857 a day, while those at lower altitudes get Rs697,” he said. “Since 2017, there has been no pay hike.”

In contrast, labourers working with civilian companies in Ladakh earn Rs1,000 and Rs650 at higher and lower altitudes, respectively. The demand for better pay is shared by all porters. They rely on Stobdan to claim compensation after accidents. Pointing to the list with the names of porters who lost their lives, Stobdan said 19 individuals received only Rs16,320 each as compensation. All porters are insured for Rs1 lakh in case of death by avalanches, falling into crevasses, or enemy fire.”

After the amendment to the Workmen’s Compensation Act of 1923, which determines compensation for the families of porters in case of injury or death, the families of two porters received Rs16 lakh each as compensation,” said Stobdan.

Tsering Sandup, a BJP councillor from Panamik, has been working to address the concerns of Siachen porters. “They have been supporting the Army for generations,” he said, pointing out that only the Army could help the porters. “If I ask the lieutenant governor of Ladakh to help them, his office will seek a report from the Army,” said Sandup.

He said the Central government realised the importance of the porters during the 1999 Kargil War, and the compensation increased. “That was good money then, but not 25 years later. That is why many porters now prefer to work with civilian firms and the General Reserve Engineering Force (GREF), the parent cadre of the Border Roads Organisation (BRO). There is no risk involved with GREF, and a porter returns home the same day,” he said.

For many who could not make it to the Army, the job of a porter is all about living that dream. The ceremonial honours the deceased porters receive―with flag-draped coffins and gun salutes―inspire others. “Siachen porters cannot be compared with those who work with civilian firms,” said Sandup. “They should be protected under better insurance so that their families do not suffer in case they lose their life while on duty.”