In a dim courtroom with forsaken walls, surrounded by lawyers, petitioners and spectators who have no business being present for the case being heard, a family court judge in Lucknow tells the 27-year-old woman before him: “If the husband wants to keep you, why don’t you go to him?” The woman’s choice, her petition alleging physical abuse, and the three years she has spent attending every hearing, dissolve into nothingness. Later, she tells this correspondent that the judge’s remark made her feel like a piece of furniture.

The case of Atul Subhash, the Bengaluru techie who ended his life alleging harassment by his wife and her family, has stirred a frenzied debate on how laws to protect women are being misused. But as Nausheen Yousuf, a Mumbai-based lawyer with 17 years of matrimonial litigation experience, says, “To misuse the law, you first need to know it. How many women have that privilege?” And, by extension, how many men?

In Subhash’s case, we know one side of the story. We know it because of a well-made, viral video. But it cannot be the only side. Just as Subhash’s cannot be a wholly false narrative.

According to Bhupendra Singh Bisht, a lawyer, “Section 498-A of the Indian Penal Code (commonly known as the anti-dowry law) can be a tool to wreak vengeance.” He explains with the example of a woman who abandoned her marital home after some differences arose. When many attempts by the husband― Bisht’s client―to reconcile failed, he filed for divorce in the family court of Dehradun. The court sent summons to the woman to appear and explore the possibility of mediation. When this bore no result, a warrant was sent. She, in turn, lodged police complaints under sections 498-A, 323 (intentionally causing bodily harm), 504 (disruption of public peace through intentional insults or provocations), 506 (criminal intimidation), and sections 3 and 4 (taking and demanding dowry) of the Dowry Prohibition Act. These complaints were later withdrawn when the husband agreed to pay alimony.

Swarup Sarkar, the founder of the Save Indian Family Foundation (SIFF), an NGO established in 2005 to protect men unfairly targeted by dowry prohibition laws, says the wording of laws such as these, and the Domestic Violence Act (2005), are inherently unfair to men. The DV Act was intended as a kind of middle ground. For example, it grants a woman (and her children) the right to reside in the marital home while approaching the courts. Thus, it offers women both the safety of a home and the means to break free from an abusive relationship they would otherwise remain trapped in if they had no place or no one to turn to.

“The law assumes that only women can face abuse. While we agree that, biologically, more women might experience physical abuse, it is unfair to suggest that men do not face verbal, sexual and emotional abuse. Similarly, the dowry laws give women the right to name any relative of the husband as complicit in the crime. Our humble submission is simply this: men can also be at the receiving end,” says Sarkar.

The SIFF operates a helpline with a common number that works across the country. Since 2014, it has received an average of 112 calls per day. There was a dip in the number of calls after 2014, the year when the Supreme Court (in Arunesh Kumar versus State of Bihar and others) ruled that police officers must not automatically arrest the accused when a case under Section 498-A of the IPC is registered. Instead, they must satisfy themselves about the necessity for such an arrest.

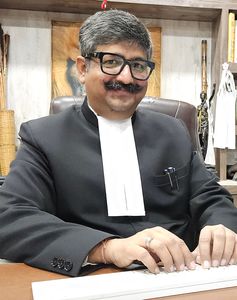

Human relationships are a vast grey area. Syed Mohammed Haider Rizvi, an advocate specialising in family law, says the rising number of cases in family courts, including maintenance, child custody and dowry harassment, often stems from “clashes of ego between estranged couples, which can be exacerbated by advocates who fail to recognise their broader responsibility as social reformers”.

He says there is a need to find solutions that prioritise the well-being of all individuals involved, especially children. “The goal should be to create a more compassionate and effective family court system that promotes reconciliation, understanding and the best interests of all parties involved.”

Yousuf, who has experience practising at various levels from trial courts to the High Court, says, “There is a need for systemic changes at the execution level rather than at the level of the law.” She highlighted two well-known drawbacks of the system: too few judges, and lawyers who deliberately prolong cases. She cited the example of a client who had been waiting for eight years to get a divorce and was unable to find employment because her estranged husband smeared her name at workplaces while paying no alimony.

Yousuf also pointed out that, often under the pretext that a woman was misusing the law, lawyers would extort money from their male clients. For instance, they might suggest anticipatory bail by stirring up fear that the woman might file a case under Section 498-A.

Making posts in the lower judiciary more attractive is one remedy that is discussed often. But there are other solutions as well. If, for example, the presiding judge in Subhash’s case had demanded money for deciding the petition, there should have been a complaint to a higher judge. The corollary is that Subhash should have been aware of that option and that his lawyer should have taken that route.

Back in that dim courtroom in Lucknow, the woman who squirmed at the judge’s suggestion endured another decade of agonising waiting to get her divorce. If Subhash’s case was a tragedy of death, hers was a tragedy of the living.