It was dinner time. In the Saraswatpur residence of the Karnads in Dharwad, the mother told the father casually, “And we had thought we did not want him!” She was referring to her fourth child. The jolted son, in his mid-30s, prodded her to reveal more. She confided that they wanted to terminate the pregnancy, while she was carrying him. But, when the doctor did not turn up after a long wait, they gave up the thought.

The mother’s revelation was immortalised when theatre giant Girish Karnad put it in his autobiography, Adadata Ayushya. He dedicates the book to the “life-saviour” doctor, Madhumalati Gune, who never turned up on the fateful day.

Karnad’s creative exuberance gave life to the characters drawn from the past and the present. They spoke, poked, pondered, prodded and, at times, provoked the receptive minds. In life, he donned many hats: playwright, actor, director, artist, rights advocate and administrator. But when Karnad, 81, bid adieu to this world, he did it quietly. The farewell to the Jnanpith awardee was simple, private and sans worldly moorings—no rituals and state honours. He had wanted it that way.

Born into a Konkani-speaking Saraswat family in Matheran, Maharashtra, on May 19, 1938, Karnad moved to Sirsi, Karnataka, with his family—Dr Raghunath Karnad, a government doctor, mother Krishna Bai, a nurse, and his siblings. He graduated in mathematics and statistics from Karnatak University and pursued philosophy, politics and economics as a Rhodes scholar at the University of Oxford, from 1960 to 1963. His aspiration to become an English poet was soon replaced with the urge to be a Kannada playwright. His first play—Yayati, the story of a mythological king, was penned in 1960, while he was still in Oxford. But it was Tughluq (1964), the story of the 14th-century sultan of Delhi Muhammad bin Tughluq, that was the most celebrated. It was staged in multiple Indian languages by different theatre groups.

In 1974, Karnad was awarded the Padma Shri for his contributions to theatre. He was just 36. He was later honoured with the Padma Bhushan (1992) and the Jnanpith award (1999). He served as the director of the Film and Television Institute of India and as the chairman of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

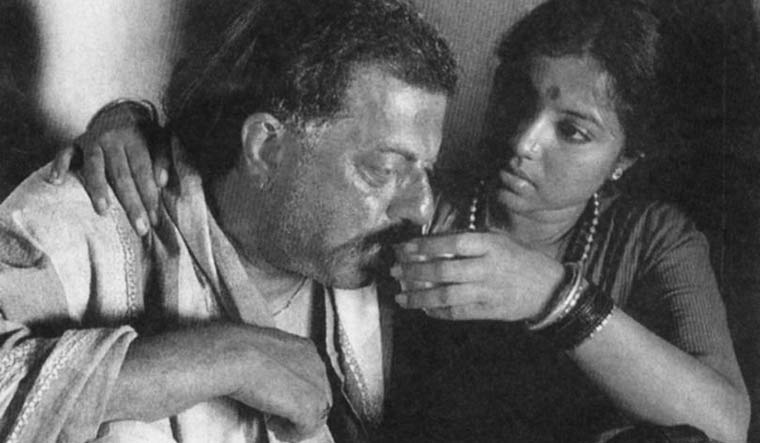

Karnad dabbled in many worlds—art, literature, drama and music—to stir up a youthful ensemble, where myth meets history, the classical blends with folklore and modernity complements tradition. His entry into films was accidental. During his stint as a manager with the Oxford University Press in Madras, Karnad worked with a theatre group to stage English plays. One day, he decided to make a movie—Samskara, an adaptation of a novel by Dr U.R. Ananthamurthy. Karnad, who wrote the screenplay, also transformed himself into Praneshacharya, the lead character. The actor had arrived.

Karnad also directed the critically acclaimed Hindi film, Utsav (1984), an adaptation of Shudraka’s fourth-century Sanskrit play Mricchakatika.

His sterling performance as the adamant dance teacher Narayana Sharma, who takes up the challenge of teaching Kuchipudi to a dalit girl in Ananda Bhairavi, gives a glimpse of the master’s commitment to his art. Karnad learnt Kuchipudi for the movie in about a week.

The younger generation, which missed watching Karnad in the televised series based on R.K. Narayan’s Malgudi Days, experienced his acting prowess in films like Pukar, Iqbal, Dor, Aashayein and Salman Khan starrers Ek Tha Tiger and Tiger Zinda Hai.

The constant comparison of Karnad with his contemporaries is inevitable. But it was Karnad’s non-reluctance to work with his “rivals” that was remarkable. While Samskara or Vamsha Vriksha prove this point, his good friend and Jnanpith awardee Chandrashekara Kambara recalled Karnad as “friendly and competitive”.

Karnad had his share of controversies, too. At times, he shocked the literary world by calling out stalwarts for their “deficiencies”. During the Tata Literature Live festival in Mumbai in 2012, Karnad criticised Nobel laureate V.S. Naipaul and said his book India: A wounded civilisation was a “rabid antipathy to the Indian Muslim”. Karnad shocked everyone when he called Rabindranath Tagore a “good poet but a second-rate playwright”.

From attempting to show Tipu Sultan as a dreamer and not a tyrant in Tippuvina Kanasugala, to joining the protest rally against beef ban, Karnad did things that irked the right-wing groups. Last September, when the Maharashtra government arrested writers in connection with the Bhima Koregaon violence and labelled them as “urban naxals”, Karnad joined rights activists at the literary meet for tolerance held in Bengaluru. He had a placard hanging around his neck that said, “Me, too, urban naxal”.

For the last few years, Karnad, who was suffering from a debilitating respiratory disease, used to travel with an oxygen cylinder hooked to a nasal cannula. But he was not done yet. “Karnad had made notes for three new plays and was working on his comprehensive autobiography,” revealed documentary filmmaker K.M. Chaitanya.