This is the season of unrest. Of mass protests, demonstrations, leaderless movements, youth rebellion and social revolution. Some analysts suggest that the year 2019 levels up with the roaring 1960s in the number of protests worldwide. It is certainly the highest in a decade. The world is howling and raging, and is blazing against the march of authoritarianism, the looming climate crisis, endemic corruption and inequality, and ethnic and religious discrimination, from China to South America to the Middle East to India, which has seen persistent fury against the Citizenship (Amendment) law.

Heartfelt slogans and strident poetry aside, the visuals of breathtaking crowd formations—the sea of humanity chanting in unison, the throng of protesters surrounding a flagpole, the churn of mankind with raised fists—portray the art of solidarity and the power of collective frenzy. Some canvases subconsciously and effortlessly tiptoe around the imagery of the multitude, the gaggle and the rabble, perhaps indicating that people are alive and well. That people are all we have.

Mumbai-based artist Apurba Nandi likes to fiddle around with constellations of human forms. For him, looking at people is cathartic. He keeps looking at them until they get reduced to a pattern of heads, eyes and sound. That sound is a collective humming. These formations become an inquiry into the order of society and our own sense of existence in the social fabric. Nandi, who has worked in sculpture, painting and drawing, had exhibited an acrylic-on-canvas for the Palette art gallery at the recently concluded India Art Fair in Delhi. Titled 'From All The Sides', it showed a long straight line of people against an explosion of what seems like a pixelated mass. “The line can be a metaphor for power and also of waiting, that is creating a sort of fracture in the space,” said Nandi.

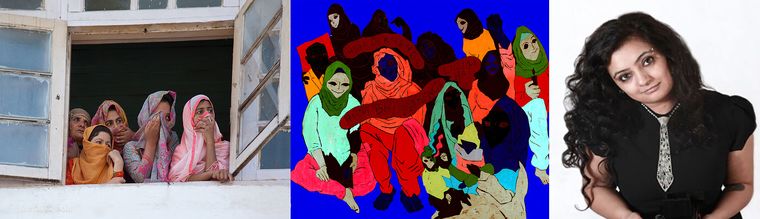

One of the most overtly state-of-the-nation images on people and politics is by Kashmiri photographer Saadiya Kochar, who juxtaposed a group of women in hijab looking out of windows in Kashmir with caricatures of local women from Shaheen Bagh huddled at the protest site. It is part of a series called '2019'. Kochar has covered the conflict and protests for a decade in the Kashmir valley. But now she knows that the fear has seeped into our homes. “'2019' is the silence that engulfs the valley and the voices that speak against all odds,” said Kochar. “The pictures are from my home in Delhi and from my home away from home in Srinagar. In 2019, the roles have reversed—the valley has gone silent and my home is imploding. The only thing common is the uncertainty.”

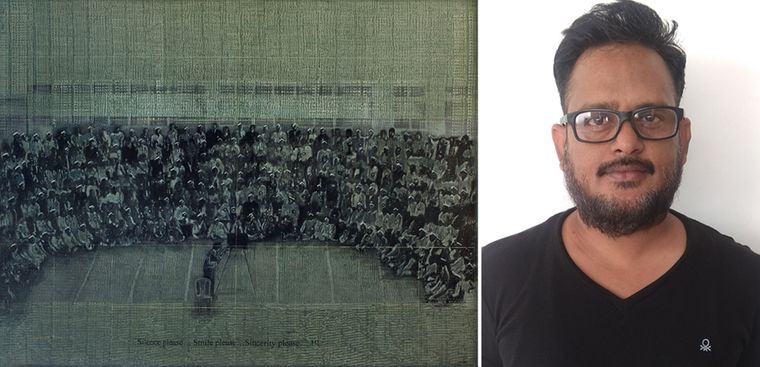

Baroda-based Balaji Ponna, a printmaker from Andhra Pradesh represented by Art Centrix, also employs his humanscapes to comment on “our dystopic times”. Almost as a snide remark, he titled his oil-on-canvas 'Silence please... smile please... sincerity please!!!' Here he has used grids, soot and similar devices to show a gathering of lawmakers in Gandhi caps facing a cameraman in the middle. They are being urged to pose more truthfully. This post-Independence setting is completely engulfed in the urgent appeal for sincerity. The 200-odd people in canvas are also a billion. If lies and false promises are a game of Chinese Whispers and has a dominoes effect, even the truth can multiply, proliferate and flourish.

And for Chennai-based artist Vijay Pichumani, represented by Art Houz Gallery, water scarcity has become the bane of existence. He has travelled across the country in his motorcycle and lived through the perils of water shortage. In 'Nila Water', which was sold for Rs12 lakh at the India Art Fair, shows a line of harried women in saris, their hair pulled back in tight buns, waiting with vessels. Although a literal representation of the civic issue, the sheer size of the artwork (a giant four-panel, 8x16ft wood-cut) has an overwhelming impact. “Of course, it has to be big,” said Pichumani. “The problem itself is gigantic and women bear the brunt of it.”

In Gigi Scaria's sculpture for Vadehra Art Gallery, titled 'Camp', the motif of aggregation is transposed from humans to a circle of houses. This bronze, high-relief wall sculpture with oxidised green roofs directly squares up to the architecture of refugee camps and detention centres. They seem skeletal even though they are simmering with life, mirroring the fragility, uncertainty and the unrelenting impermanence of the displaced. The vicious cycle of un-belonging is the reason why the houses are arranged in a circle. But in the harsh, forbidding circle of stern-looking houses, the artist has also embedded elements of hope and faith. “They come in as the green roofs of the camp,” said Scaria. “And the cyclical notion of camps also reveal the togetherness in this hardship, the aspect of survival where we also help each other. History repeats these positive forces of regeneration as well.”

If crowds can operate like ants in a colony, it seems they can do miracles.