Competitive video gaming and competitive Indian parenting seldom mix well. For many parents, a child is wasting time if he is hunched over a computer or lounging on a couch playing PUBG. Would not his attention be better spent on an entrance exam, or two?

The dedicated gamer could rightfully object that it is not just a game, but a sport. There are tournaments to be won with purses running into crores, and excellence demands practice. “Sachin [Tendulkar] once said he hit a ball one lakh times,” says Akshat Rathee, cofounder and managing director of NODWIN Gaming, a leading eSports solutions company.

The eSports professional is leagues above the casual gamer. “For the first 0-200 hours of play, you just love the game; 100-500 hours in, you build game skills; 500-1,000 hours in game, you are building team skills,” he says. “Beyond 1,000 hours is when you become an eSports athlete.”

Rathee can confirm that eSports pays off in India. His company is in the B2B side of the industry, acquiring streaming rights and distribution for the growing number of eSports tournaments. NODWIN Gaming partnered with Disney+ Hotstar to stream the ESL India Premiership 2020, “India’s flagship eSports tournament”; NODWIN also runs a show called eSports Mania on MTV India. Like any sport, eSports has hundreds of people working to make the scene happen—from players and organisers to content creators, marketers and influencers.

The Indian eSports scene had multiple tipping points for its growth: The 4G revolution, the explosive accessibility of PUBG (with over 116 million installs in India by the end of 2019, according to data company Sensor Tower), and now, a lockdown.

“The Indian video game industry is thriving, despite the widespread economic disruption caused by the coronavirus,” says Yash Pariani, founder and director, Indian Gaming League (IGL), which hosts tournaments online. “Initial data shows huge growth in playing time by up to 10 to 12 hours a day along with a 100 per cent increase in new user registrations and up to 150 per cent [increase in] sales since the lockdown began.”

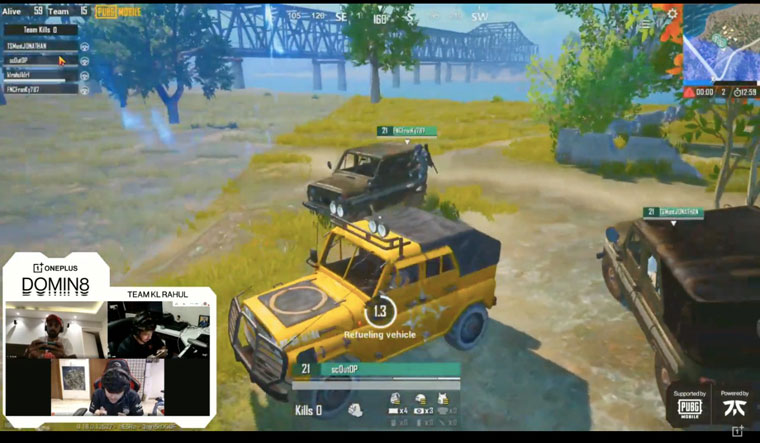

Amid lockdown, OnePlus organised the Domin8 tournament, pitting pro-gamers like Tanmay ‘Scout’ Singh against national cricketers, including K.L. Rahul and Smriti Mandhana. The company says live-streamers on platforms such as YouTube and Twitch reported a fourfold increase in viewership during the lockdown. As for eSports events, Rathee says he saw a triple-digit percentage increase in viewership in this period.

For the Indian gamer, lockdown may have created a conducive environment. “Earlier, when a kid used to play games all the time, he would be reprimanded,” Rathee says. “In a hostile environment, people do not listen to you. ‘I do not care whether it makes you intelligent, I do not care whether it is in the Olympics or not,’ he would be told. Now, he is no longer reprimanded because parents are telling him to stay indoors.”

The challenge with eSports is that games like Counter-Strike:Global Offensive (CS:GO), PUBG and Defense of the Ancients (Dota) cannot be equated to football or cricket—videogames are publisher-owned and copyrighted. For example, were the Olympics to have a first-person shooter category, how would it justify, say, choosing Valve’s Counter Strike series over Activision’s Call of Duty franchise?

This is partly why Rathee does not feel eSports will make it to the Olympics, or that it should be included at all without the publisher agreeing.

In 2017, the International Olympic Committee said that eSports could be considered a sport. But, by the end of 2019, it took the view that “the sports movement should focus on players and gamers rather than on specific games.”

However, simulation titles based on Olympic sports could play a role in the coming Games. And there has been no greater driver for simulating sport at a distance than Covid-19.

In April, just 10 days after the Australian Grand Prix was cancelled after an engineer tested positive for the virus, the Virtual Grand Prix was announced. While virtual F1 has been around since 2017, the 2020 series was marked by the absence of the physical sport. According to eSports Charts, the six virtual Grand Prix Series in Monaco, Spain, the Netherlands, China, Vietnam and Bahrain had nearly 18 million viewers put together—and that is only on Facebook, Twitch and YouTube.

Training game

For players, life under lockdown has been a mix of training to get better and training to relieve monotony.

Says Samir ‘Kratos’ Choubey of TeamIND: “For the [PUBG Mobile Pro League], we have cut practice sessions. Our schedule is to wake up by 11am, freshen up and eat by 12:30pm. By 1pm, we start with warmup sessions and drills.”

“In this current lockdown, we have decided to have more breaks as it is really unhealthy for our players to stick with their devices all the time and not go out. We often have other side games and fun with each other. It is really important for us to keep our players happy and [it is] not just about performing on competitive platforms," he adds.

Neeraj G.V. aka TheBONES, a professional CoD Mobile player, says, “In my case, I would wake up late in the morning or in the afternoon due to late-night gaming. Then get ready and have lunch. After that, I chill on Netflix or YouTube for a while before I start gaming with my friends or play IGL tournaments. Then have dinner and chill on Netflix or YouTube before a night session of gaming. I go out for fresh air during the free time in between.”

The stakes grow larger with each event. The recently-concluded PMPL South Asia had a $138,500 prize pool. The ESL India Premiership 2020’s sponsors include Mercedes-Benz and Red Bull. Professional PUBG Mobile players in India can make up to Rs 50 lakh a year, says Rathee.

From big brands advertising with cricket players, we now have cricket players advertising eSports (the Domin8 tournament). Telecom brands—whose services are crucial to mobile gaming (the dominant gaming sector in India)—are diving into the fray; Airtel has partnered with NODWIN Gaming to create an Indian eSports ranking system. Reliance Jio is said to be considering an entry into eSports, too, after having invested in talent to work in its eSports division.

The signs are promising. More people watched the League of Legends World Championship Finals than the Oscars. The prize pool for Dota 2’s The International 2019 tournament, at more than $34 million, was more than thrice that of the 2019 ICC ODI World Cup.

Yet, taken together, these facts still fail to paint a complete picture of the state of eSports as a whole. Viewers for a LoL match represent just the fans of a single type of game. Sporting prize pools do not account for money earned via sponsorships or media rights (the industry is worth $822 million globally, according to a Newzoo report).

So, can Indians make a mark in eSports? The signs are inspiring. Fnatic, one of the world’s most renowned eSports organisations across multiple titles (sort of like if Manchester United fielded teams in multiple sports), maintains an all-India roster for its PUBG Mobile team.

When Samir ‘Kratos’ Choubey started gaming professionally, he did not tell his parents about it. Now, he says his dad watches all his matches, and probably knows more about the game than him!

The future of eSports, at this pace, is bright.