For rapper Hiran Das aka Vedan, everything he sings is political. His politics, which stems from his upbringing in an unprivileged colony in Thrissur, Kerala, carries the wounds of systemic marginalisation that his people have faced for centuries. So, when he released Voice of Voiceless in June, it became the most viral political rap in Malayalam ever. His words, “Kannil kaanatha jaathi matha verppaadu, yuganagalayi thudangi iniyumenne vettayadu (Caste and religious divides that you choose not to see have been hunting me down the ages)”, made the usually bubbly Malayali social media users stop and listen.

“I have faced casteism in my life,” says Das. “Though I talk about communities from Kerala, the song is about everyone who faces casteism. Those who ask, ‘Where is casteism in this country?’ are blind about this massive problem around us.”

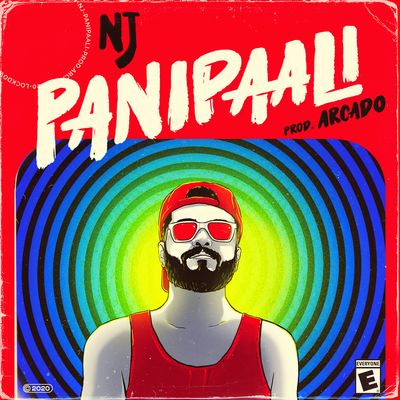

A few weeks after the release of Das’s song, another Malayalam hip-hop number broke the internet. Written and sung by actor-rapper Neeraj Madhav aka NJ, and produced by Arcado, Panipaali (Messed Up), became an overnight sensation. Panipaali’s success rode on its funky beats and fantasy elements. The song’s comic book-style video has already earned more than 1.8 crore views on YouTube (as on August 26). “The song talks about the distorted sleep schedules of the youth,” says Madhav. “I intended to keep it commercial, and at the same time, stay true to the hip-hop genre.”

Madhav is known for his acting and was in the recent Amazon Prime Hindi series The Family Man. However, his rapper persona, NJ, was revealed only recently. “Since my childhood, I had an affinity for beats and rhythm,” says Madhav. “Kerala has a strong underlying rhythmic setup—we have musical forms like vaaythaari (orations) and vanchippattu (boat song), and percussion instruments like chenda and mrudangam. My interest in these may have formed my base for hip-hop, too.”

Hip-hop in India gained prominence with rap battle communities like Insignia and Battle Shelter rapping in English. The late 2000s saw the emergence of regional language hip-hop subgenres in India. The founders of the 2009-born alternative hip-hop collective from Kerala, Street Academics—Rajeev M. aka Pakarcha Vyadhi and Haris Saleem aka Maapla—are counted among the pioneers of Indian rap.

The Malayalam rap scene languished in relative obscurity until recently, though there had been an underground community of hip-hop enthusiasts in Kerala for over a decade and a half. Songs like Voice of Voiceless and Panipaali have finally brought a mass appeal for the genre.

“Malayalam is not an easy language to make hip-hop songs in,” says Madhav. “The language’s phonetics is pretty difficult. It has long words that make the lyrical flow tough. It does not have the ease of English, Hindi or Tamil.”

Initial attempts to popularise rap in Malayalam were limited to parodies of popular English songs. But the trajectory of Malayalam hip-hop took a new direction in 2010 when Street Academics released a fiery political bilingual track, Repping the Truth, featuring Saleem. The other members of Street Academics are Amjad Nadeem aka Azuran, Arjun Menon aka Imbaachi and Vivek Radhakrishnan aka V3k, and their themes range from social realism to dystopian fantasy. Their most acclaimed songs include 16 Adiyanthiram, Chatha Kakka, Aathmasphere, Kalapila and Pambaram.

Many others like Danny Varghese aka Achayan, Remeez Musthafa aka rZee PurpleGaze, Sanju Jaison aka San Jaimt, Sarath Sasidharan aka Nomadic Voice and Febin Joseph aka Fejo also came up with original hits in the last decade. But they had to build the Malayalam hip-hop subgenre from scratch. Remeez released his first original on YouTube in 2014, but that was six years in the making. “I put in rigorous effort in writing and rewriting the songs, and learning beat production,” he says.

Rajeev also recalls the struggling days of his collective. “We had to do all the mixing, mastering, shooting and video editing ourselves,” he says. “We had no model before us [in Malayalam rap] to take a cue from.”

The absence of a rap-literate audience was also a problem. “I have been a live performer for almost 14 years,” says Rajeev. “I used to perform along with folk singers, doing fusions with them. Back then, I used to get reactions like, ‘Ee chekkanentha ee kanikkunne? (What is this guy doing?)’.”

Rajeev adds that over time, people started understanding the genre better, and that in the last couple of years, there has been a major boom in regional hip-hop communities in India. He credits the increased accessibility to music and hip-hop’s adherence to grassroots for this rise. “The origin of hip-hop itself has to do with [overcoming] limitations. You can start making hip-hop with zero-investment,” he says. The proliferation of low-cost music software and hardware and short-format video platforms has also played a significant role in the current boom.

Kerala, though, still lacks a strong independent music industry. “There are limitations for musicians to try something different in film songs,” says Madhav. The absence of film releases during the Covid-19 lockdown has helped this music genre rise and shine.