In 2012, when legendary Bengali writer Sunil Gangopadhyay died of cancer, I called his dear friend Soumitra Chatterjee. “I am feeling down, and do not know how to react. Almost all of my friends have left me. I feel really lonely,” the actor said.

Perhaps he became indifferent to the idea of death after the loss of so many friends, because at the age of 85, he chose to return to the film set while Covid-19 was reaping lives in the hundreds every day. His argument was that Covid-19 would stay but life could not stand still. Sadly, fortune did not favour this brave man; he died on November 15, a month after being infected.

Chatterjee was theatre’s gift to the silver screen. Mentored by Sisir Bhaduri—the father of modern Bengali theatre—Chatterjee was a theatrical prodigy as a student of Calcutta University. His talent caught the attention of many luminaries, including actor Utpal Dutt.

In 1957, when Chatterjee was 22, he was called up by Satyajit Ray, who was scripting Apur Sansar, his third film of the Apu trilogy. Soumitra fit the role of Apu—he was tall with attractive eyes and an innocent but intelligent look. His performance and the film attracted much critical acclaim from around the world. In 1960, when it was screened in Washington DC, US president John F. Kennedy was in attendance as he had read glowing reviews of the film in British newspapers.

In Apur Sansar, Chatterjee gave us one of the finest moments of Bengali cinema when his character Apu learns of the death of his wife in childbirth—an expression of bewilderment, followed by intense grief that leads Apu to disown his newborn son.

Chatterjee follows it up later in the film with another powerful bit of acting, when Apu realises that his wife continues to live through the son that he rejected. Ray’s imagination and powerful direction coupled with Chatterjee’s spellbinding performance gave us a classic. That was the beginning of the Ray-Chatterjee partnership that lasted for three decades and 14 films.

“It was the first Indian film I had seen in my life,” Argentine filmmaker Pablo Cesar told THE WEEK. “After that, I saw every Satyajit Ray film. I cried profusely watching Apur Sansar. What a performance by Soumitra Chatterjee!” Actor Aparna Sen said that she feels Ray would not have made Apur Sansar without Chatterjee.

Similarly, Ray’s Charulata (1964) starring Chatterjee, too, won plaudits. Charulata was preserved by Academy of Film Archives in Hollywood in 1996 as a world cinema classic. The film depicted the suppressed physical desire of Bengali women, who were restricted to their homes. Chatterjee’s Amal mesmerises Charu (Madhabi Mukherjee) with his poetry and beautiful voice as he recites Rabindra Sangeet. The chemistry between the two actors made the film memorable.

Chatterjee was the intelligent face of Ray’s pathbreaking films till Ganashatru (1989), where he beautifully essayed the role of a doctor who could not survive the pressures of religious dogma. Another notable role was in Ray’s Ghare Baire (1984), with a controversial portrayal of the many sides of an Indian freedom fighter.

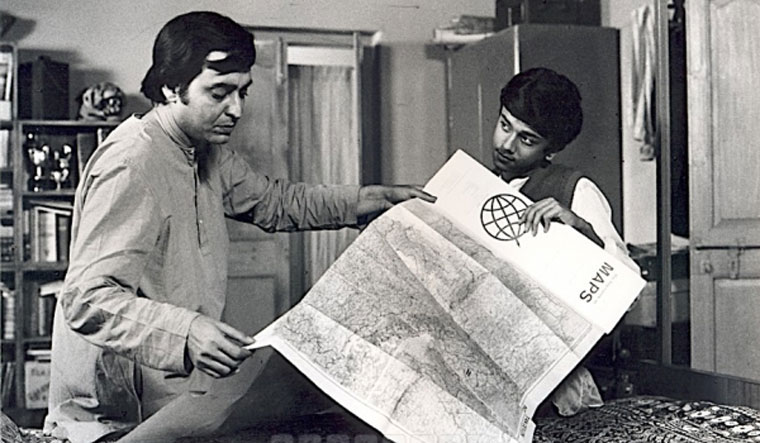

When he became Ray’s detective Feluda, Chatterjee’s brilliance made it one of his most memorable roles. In the detective series that Ray wrote, the sketch of Feluda looked a lot like Chatterjee, though Ray made only two movies out of the numerous Feluda stories he wrote.

Despite playing serious and intelligent men in Ray’s classics, Chatterjee was equally successful in commercial Bengali cinema, too. Be it Tapan Sinha’s Kshudhita Pashan (1960) or his comic portrayal in Teen Bhubaner Pare (1969), Chatterjee made an indelible mark in every film. He had the gift of fitting into any type of character he was given.

He was an outspoken actor, too. One of his most famous dialogues, “Fight, Kony, fight!” from the film Kony (1986) was his mantra. He plays a swimming coach who trains a girl to become a champion by overcoming various political hurdles. Chatterjee was a lifelong Marxist and did not hide it. He was an active participant in the Indian theatre movement. But despite being close to communist stalwarts Jyoti Basu and Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, he never joined politics.

He was a Bengali purist, who spent most of his time writing stories, painting and reciting Tagore’s poetry. Admittedly, towards the end of his career he worked in a few films that did not really appeal to him. But, for his pathbreaking roles, he will go down not just as a legend of Indian cinema, but of the world.