For 31 years, Joe Foster’s life ran parallel to the shoe company that he built. Until his shoes outpaced him. “It had become a big company that was being run by numbers,” he tells THE WEEK. “And I was just taking it light—getting picked up in limousines, meeting nice people, having nice meals…. By that time, the challenge was gone. The journey, for me, was at an end.”

It all began in 1942 when seven-year-old Joe won a Webster’s dictionary at an athletics event in Bolton, his hometown in northwest England. The dictionary was to come in handy 18 years later, after he and his brother, Jeff, started a shoe company called Mercury, only to realise that the name had already been taken by Lotus and Delta, a division of the British Shoe Corporation. They were advised to “choose a made-up name, something nobody else would have thought of”. A disillusioned Joe flipped through the dictionary, his finger trailing random names in it. Mamushi? Mamzer? Redwood? No, no and no. Until he came to Reebok: “A light coloured antelope”. Perfect. It was short, catchy and easy to pronounce. It suggested light, but fast and agile.

Reebok’s journey, however, was neither light nor fast and agile. There were seemingly insurmountable hurdles. Like when they got a winding-up petition from a patent office wanting to close down the company. Or when Lawrence Sports, the worldwide distributors of Reebok, went bust. Or when faulty manufacturing by Bata caused the mid-soles of around 20,000 pairs of Reebok to collapse. But when a door closed, a window always opened. Joe first met Paul Fireman at a trade exhibition in Chicago in 1979. Fireman was key to Reebok’s success in America. Five years later, Fireman, along with Stephen Rubin, the CEO of ASCO, a subsidiary of the Pentland Group, would buy the company from Joe.

“I sold the brand for what at the time was a reasonable figure…. None of us in our wildest dreams thought Reebok would go on to become a multi-billion-dollar company,” writes Joe in his new memoir, Shoemaker: The Untold Story of the British Family Firm that Became a Global Brand. “If I had an inkling that it would, then, yes, maybe I would have retained some kind of share. But there is no point in looking back at unknowables.”

In many ways, Joe measures the milestones in his life through specific Reebok shoes. There was the Aztec, for example, that opened the door to America. The nylon and suede shoe which came in blue, red and yellow was one of three Reebok shoes that was given a five-star rating by the prestigious Runner’s World magazine in 1979. Those days, the magazine’s rating was the acid test to determine the success of a shoe in America.

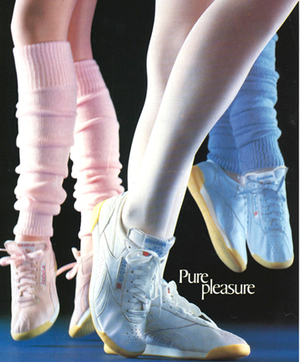

But it was really the Freestyle that propelled Reebok to global fame in 1982. It was the idea of a Reebok sales agents, Angel Martinez, who noticed, while joining his wife at her aerobics sessions, that women did aerobics either barefoot or in uncomfortable trainers. He quickly recognised the need for specialist aerobics shoes. The Freestyle, made with soft glove leather lined with adhesive nylon, was the first fitness shoe specifically designed for women. It was an immediate success, with everyone from celebrity fitness guru Denise Austin to Hollywood actor Jane Fonda endorsing it. The shoe played an instrumental role in Reebok’s sales skyrocketing from $1.5 million in 1981 to $13 million in 1984.

Success, however, came at a price. Joe’s family life suffered and his first marriage ended in divorce. “As with my dad before me, and his before that, work and family were separate entities, linked only by the one providing necessities for the other,” he writes. “Business gain was my driving force, or rather my obsession.” It was a tough trade-off, especially when his daughter Kay, to whom the book is dedicated, died of leukemia in 1988. “It was the last day that my heart would ever be whole,” he writes. In fact, after her death, the tone of the book changes, striking a softer and sadder note. The high-octane life of glitz and glamour gives way to the gentler one of retirement and rest. “I started living at my pace, instead of Reebok’s,” says Joe, currently settled in the Canary Island of Tenerife with his second wife, Julie. “Yes, I would have liked Kay and my brother Jeff to see the success of Reebok,” he says. “It did not happen, but you can’t change that. You wish you could, but you can’t.”

Joe is content with his life now. “I enjoy sitting out here and just being still,” he says. It took him some time to get used to it, though. Initially, he would wake up thinking, when is the next plane? He recounts how Nike’s founder Phil Knight was once asked what was left on his bucket list. He replied that if he could do it, he wanted to do the journey all over again. Not Joe, though. For him, the memories are enough. “It was fantastic to have done it, but great to come out of it,” he says. Still, you can take him out of Reebok, but you cannot take Reebok out of him. “It is like the [lyrics of] Eagles’ ‘Hotel California’,” he says with a chuckle. “You can check out, but you can never leave.”

Shoemaker: The Untold Story of the British Family Firm That Became a Global Brand By Joe Foster

Published by Simon & Schuster

Price Rs699; pages 319