Early in 1983, American radio consultant Lee Abrams said, “All my favourite bands are English…. It is a more artistic space. Experimentation thrives there. Everything over here is more like McDonald’s.” It was an exhilarating time to be alive in 1980s Britain, during the peak of the ‘new wave’, when music transitioned from punk and rock to electronic synth-pop, and acts like New Order and The Cure ruled the charts.

“The 1980s were the best time of my life,” says Nermin Niazi, who, along with her brother Feisal Mosleh, came out with a record in 1984, Disco Se Aagay, which was unique in the way it married Urdu lyrics with the reigning disco and post-punk music of the day. “It was a time of innovation and experimentation with music. Suddenly there were all these instruments. There were the new romantics and experimentation with makeup and the way you dressed.”

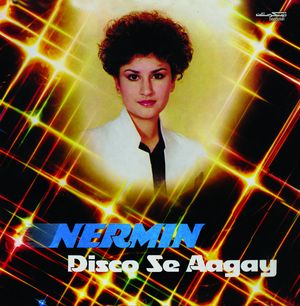

She refers to the cover of Disco Se Aagay, in which she is wearing a shirt and dinner jacket. “I am wearing non-gender specific clothes and I liked that because it gave me a certain kind of power, because I was making a statement as a British-Asian woman, that I did not fit in a box and that you could not compartmentalise me. The cover very much spoke of who I was in the 1980s.”

Nermin and Feisal came from musical royalty. Their grandfather was the director-general of Radio India. Their father, Moslehuddin, was a famous Bengali music composer and their mother, Nahid Niazi, was a playback singer. When the brother and sister were six and one respectively, the family shifted to England from Lahore following the Bangladesh war of 1971. “I was only a child of three or four when I started going to recording studios with my parents,” says Feisal. “Sitting in front of the cameras, dancing around, singing…. Many of the artistes we listened to were people we actually knew. We had dinner with them and sat with them during their sessions. I even recorded some famous people, like [ghazal singer] Mehdi Hassan, on my own personal audio system. But there was a whole range of artistes from the West as well, from Abba to Pet Shop Boys and Depeche Mode, whom we listened to.”

One day, Feisal was bored and started experimenting with their father’s string orchestra. Nermin came in and started humming to his music. And before they knew it, they were collaborating. When their father realised that they had an interest in music, he contacted a music company called Oriental Star Agencies in Birmingham—known for discovering the famous qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan—which expressed an interest in recording an album with them. And that is how Disco Se Aagay happened.

“We were very diligent about our music because we had been raised by two professionals,” says Nermin. “So we would often have many things ready before we went to the studio, because studio time was expensive those days. The recording studio, Zella Studios, was a converted church. My first impression as a 14-year-old girl was going up these brick steps to this building that essentially looked like a church.”

Disco Se Aagay combined Hindustani melodic scales with synthesisers like the Roland June-60 and Yamaha DX7. The nine songs in the album, recorded when Nermin and Feisal were 14 and 19 respectively, have a raw, almost primitive, feel. There is something unpremeditated, a roomy abstraction, to them. A few jarring notes are there, but the charm of the record is its honesty. “My brother took care of the technical side,” says Nermin. “I spent more time on the creative side, where I used my instinct to compose my vocal arrangements. The reason why the album is so unusual is that it was a snapshot of the time in which it was recorded. Our ages, too, had a lot to do with it. We were so young and innocent that we just let it develop. If we had been older, maybe we might have been a bit more controlling about the process.”

Interestingly, Nermin says the album played a significant role in gaining her acceptance among her British friends. “I went to a girls’ school. Because I faced some racism, I did not draw attention to myself, so had told no one about the album,” she says. “We had given an interview a week before school reopened after summer vacations, which had been published in the local newspaper. In school, there was a long corridor which led to the courtyard and the classrooms. When I went there on Monday, the girls standing in the corridor were pointing at me and whispering. That’s when my friends told me that I had [been featured] in the newspaper. The [clipping with the] interview had been put up on the main notice board. I think it was titled ‘Asian girl, star of disco’. It was amazing because that is when my life changed at school. Suddenly, I was seen as something different by all those girls.”

Much of the record’s allure is that it was a sonic bridge between the east and the west. The teenagers’ feelings of alienation, frustration and the racism they faced, common among diaspora kids, animated their music. Ironically, it was also the reason why the album was relegated to relative obscurity then. As a reviewer wrote, it was too eastern for the west and too western for the east. It was much ahead of its time. Perhaps that is why now, 37 years later, the songs are finding renewed fame. It happened when Arshia Haq, founder of Discostan, a “diasporic discotheque” dedicated to celebrating south and west Asian and north African music, discovered the album in a second-hand record store on New York’s Lower East Side and decided to reissue it. The remastered version has been creating waves since its release in January.

It has been long since Nermin and Feisal moved away from music. Feisal did his master’s in microchip design and relocated to Silicon Valley and Nermin joined the Metropolitan Police in London. The bittersweet strains of Disco Se Aagay festoon a simpler time for them, an age of innocence.