It is commonly said that clothes make the man or woman. But more than just appearance, clothes are also about stories. Stitching together the stories of trousers, saris, pagri, purses, embroidery and much more is Jasvinder Kaur’s Influences of the British Raj on the Attire and Textiles of Punjab—a book that brings alive fashion that once was.

Much has been written about the British and the influence that the Raj had on various aspects of life, but clothes do not find much mention. Kaur, however, has chosen to focus only on the outward appearance to weave together the empire’s impact on dress. From the embracing of coats, shoes, socks and trousers—the last to be adopted because it was not easy to sit on the ground in them—Kaur chronicles the change that swept through Indian life.

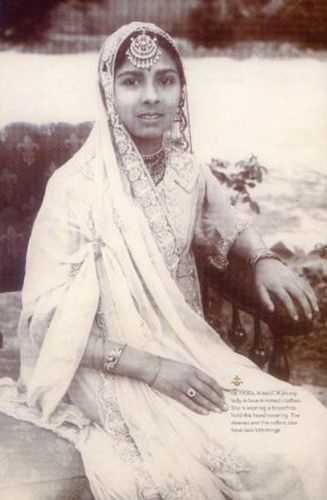

She focuses mainly on Punjab, where she grew up. A treasure trove of information, Kaur writes about lace, net and thick velvet, which, with gold embroidery, became much the rage in Punjab, both for men and women. From how parachute cloth—the result of material shortage during World War II—found its way to trousseaus in Punjab, to the advent of the sewing machine, Kaur uses cloth to document the history of Punjab. More than just her nuggets, though delicious and informative, there are the pictures of decadent fabrics, dashing men and gorgeous clothes.

Lace-making came from the Madras Presidency in the 19th century. In Punjab, it did not catch on much. The first issue of India’s Woman does, however, have a reference to Fatima from Amritsar who did “good lace” work.

Did gingham checks travel to Punjab? In the 1940s, the ‘khes’ of Punjab—a rough bedcover—was woven with blue or brown checks. Some scholars, Kaur writes, have compared khes with gingham. There was a suggestion of the Scottish tartan too. “Brown silk was relatively uncommon,” writes Kaur. “For cotton checks, generally, English thread was used and there are instances of blue-and-white checkered cloth being made for ladies’ dresses at the Lahore and Multan jail.” Ludhiana became known for Ludhiana cloth—a particular type of checked cloth.

Reading her book is like discovering a trunk of clothes from your grandmother’s time—sumptuous, exotic, the repository of a bygone age. Sari blouses, she writes, became inspired by European women’s dresses of the 1860s. “The upper parts of women’s dresses were form fitting and many women either wore separate blouses with skirts or a single-piece dress,” she writes. The way the sari is draped today is a legacy of Bengal, a reason why it did not necessarily become so popular in Punjab. “In fact, anybody wearing a sari was considered as being ‘too forward’,” she writes.

However, it is not all about women’s clothing. Kaur also describes the effect of the Raj on men and their look. From waistcoats to sherwanis to the achkan—the first Indo-Western fusion outfit before designers came into the picture— Kaur manages to hook the reader, quite literally.

Influences of the British Raj on the Attire and Textiles of Punjab

By Jasvinder Kaur

Published by

Rupa Publications

Price Rs2,500; pages 167