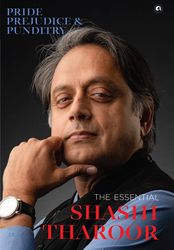

Author, MP and THE WEEK’s columnist, Shashi Tharoor has published more than 20 books, both fiction and non-fiction. His latest, Pride, Prejudice & Punditry, is a compilation of his best published works as well as fresh pieces written specifically for this volume. From articles on diplomacy and international relations to personal essays and a selection of his most famous speeches, Tharoor covers a vast array of subjects in the book.

An excerpt from the chapter, ‘A Congenital Indian Nationalist’:

The question of nationality and nationhood is not, for me, a purely theoretical issue, the stuff of political philosophy or intellectual argument. It is an intensely personal matter. I was born in London, in 1956, to Indian parents who carried the passports of their newly independent country, just six years after the establishment of the Republic of India. Thanks to the laws prevalent in the United Kingdom, I was eligible from birth for a British passport, an option I have never exercised. The choice remains available: not to make that choice is, therefore, a decision I have consciously taken.

The issue has arisen at various stages of my life. When I won a scholarship to go to graduate school in the United States, at the age of 19, in 1975, I planned to stop in London to visit relatives and friends on the way over. I duly applied for what, in those days, was known as an ‘entry permit’, and settled down in the waiting room of the British deputy high commission in Calcutta (as it then was) for my turn to pay the requisite fee and collect it. Instead, to my surprise and consternation, I was singled out and summoned to the office of the deputy high commissioner. Wondering what I had done to merit this, I nervously entered the dignitary’s enormous office, only to be told,

‘I’m afraid we can’t give you an entry permit.’

‘What have I done wrong?’ I stuttered. ‘Was there any mistake on my application form?’

‘No, not at all,’ he said with a smile. ‘You see, your birth certificate means that you are entitled to a British passport.’

‘But I don’t want a British passport!’ I expostulated. ‘I just want an entry permit.’

‘I understand that,’ said the deputy high commissioner. ‘But, you see, we can’t give an entry permit to someone who is entitled to a passport. That’s against our rules.’

I was stumped by this unexpected development. ‘Are you saying to me that I can’t visit London? Unless I take a British passport?’

‘No, I’m not saying that,’ he hastened to assure me. ‘We can’t issue you an entry permit, but they cannot deny you entry into London when you have the absolute right to live there. Just go to London and show the immigration officer that you were born there, and they will let you in. They won’t even stamp your passport.’

I nodded somewhat dubiously at this assurance, but since he refused to accede to my pleas to issue me a permit anyway, went off clutching my Indian passport and hoping for the best. It worked exactly as he had said it would: I landed at London Heathrow and was waved in without any trouble, the immigration officer even helpfully telling me that in future I could use the much shorter lines for British nationals, since, as far as they were concerned, I was one.

This happened a few more times until, in 1979, Margaret Thatcher became prime minister and decided that the entry permit system for Commonwealth citizens was too lax and that we would all require visas. When I checked with the British consulate in Geneva, the city I was based in at the time, I was told there was no provision for exceptions. So, I applied for a visa, paying the extortionate fees the British were charging in order to discourage potential immigration from the Commonwealth.

But the attractions of theatre, cricket, books, and family friends—all of whom were just an eight-hour drive and a Channel-ferry ride away from Geneva—meant that my wife and I kept going rather often to Britain, and repeated applications for a visa became a rather expensive proposition. I returned to the charge, raising with the friendly British consul in Geneva the paradox of my being eligible for a passport but having to pay through my nose for a visa every time I wanted to set foot in a country in which I was legally entitled to live.

She admitted this was irrational, and a flaw in the rules—but there was a possible way out. While tightening entry policy, Thatcher’s government had also created something called a ‘Certification of the Right of Abode’, intended principally for people of British descent, whose parents and grandparents had been born in the colonies, and who would, therefore, not be eligible under the new law for automatic entry to, or residence in Britain, even though they were plainly of British stock. Though I was not of British stock, she thought perhaps the same certificate on my passport would eliminate my problem.

A couple of head-scratching weeks later, the call came from her office: her proposal had been rejected by London. ‘The problem,’ she said apologetically, ‘is that under British law, we cannot certify an entitlement that is yours by right.’

I threw up my hands at that wonderfully British statement of principle, affirming a status while preventing its practical fulfilment. (I was all too aware that Indians have inherited this wonderful bureaucratic talent, too, thanks to British colonialism!) But the consul, a woman of great empathy as well as creativity, was not deterred. In a few days, she asked me to come back to her office. ‘I have a solution for you,’ she said cheerfully. She stuck the certificate in my passport, pulled out her pen, and crossed out the word ‘Certification’. Then, in her own hand, she wrote the word ‘Confirmation’.

‘There,’ she beamed brightly, handing me my passport. ‘I cannot certify your birthright, but there’s no rule telling me I can’t confirm it. You can use that instead of a visa.’

It worked: For a couple of decades afterwards, I was able to breeze in and out past British immigration with the Confirmation of the Right of Abode certificate in my passport, testifying to the fact that I was entitled to more than I was willing to claim. Then, computerization and standardization came in, the rules once again had to be applied with no ambiguity, and I was once again required to pay visa rates for a printed certificate (with no handwritten emendation), this time needing to be renewed every five years at an ever-stiffer fee. At one renewal, a British consular officer in New York helpfully reminded me that (at that time) it only cost 15 pounds for a passport whereas my certificate cost 65 pounds. I replied: ‘I’m happy to pay for the privilege of remaining Indian. I may have been born in Britain, but when I look in the mirror, I see an Indian.’

It is difficult to explain this nativism in one who has spent a lifetime acquiring and embodying a cosmopolitan, even globalist, sensibility, so unfashionable today in a world of growing hyper-nationalism. But, from a young age, when some of my classmates at school in Bombay teased me about my foreign birth, I have found myself consciously interrogating myself on the question of who I was. My father was an idealist of the generation that had won freedom—though, at not-yet-eighteen when Independence came, he had not personally fought for it, he had supported the nationalist movement, and, heeding Mahatma Gandhi’s call, had dropped his caste-derived surname.

In 1948, he had gone to London straight from his Kerala village, with his elder brother’s sponsorship, in much the same spirit as other Keralites starting out in life might have tried their luck in Bombay or Calcutta. Arriving as a student not yet aged 19, he had soon begun his working life there, representing Indian newspapers that still maintained offices in the old metropolitan capital. But, after a happy decade in London, he and my mother chose to return to India, because they believed that was where they belonged.

Ironically, as India descended into an increasingly corrupt and poorly functioning state, where highly taxed salaried professionals like himself found it increasingly hard to make ends meet, my father sometimes regretted that decision. But, having come back to India, he imparted to me, his first-born son, a passionate sense of belonging, not just to a physical country called India, but to the idea that it represented in the world.

That idea—of a magnificent experiment in pulling a vast, multi-lingual, multi-ethnic population out of poverty and misery through democracy and pluralism—was one that engaged and captivated me, and which I have, in one way or another, explored in over 20 books, both fiction and non-fiction. I did so even while living abroad and working for the United Nations for 29 years, which further complicated the issue for me.

For nearly three decades I was that rare animal, an ‘international civil servant’, meant to serve not my own country’s national interests but the collective interests of humanity; but I had joined an organization where my nationality defined and limited the very prospects of entry, since the recruitment of the central United Nations staff was subject to ‘geographical distribution’, and national quotas determined whether you could be recruited to a vacancy for which you were qualified. (Indeed, it was because Indians were considered ‘over-represented’ in the UN proper that I joined the UN system in the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, an agency or ‘programme’ of the parent body where no nationality quotas applied.)

If this were not contradictory enough, I found myself serving refugees who had fled their own nation states, negotiating with governments to permit other countries’ nationals entry into their territories, and later, as a peacekeeping official, interceding in wars between and within nations. At UN headquarters I worked with teams of colleagues whom I knew by their skills, talents, specializations, and peccadilloes, rather than their passports. They were ‘the field guy’, ‘the admin whiz’, ‘the brilliant draftswoman’, ‘the legal eagle’, and so on, never the Brazilian, the Japanese, the German, or the Kenyan—in the service of the blue flag, their nationalities simply did not matter.

When that career ended, after an unsuccessful though close run for the top job of secretary-general, I had the option of staying on abroad, and acquiring permanent residence in one of three possible countries. I did not. I could not. I came home, to plunge myself into the maelstrom of Indian politics, thereby making my own modest contribution to the evolution of that great Indian experiment. Leaving the world of the UN to enter Indian politics, where public figures wore their patriotism on their sleeves, I swapped my UN lapel pin for the Indian tricolour and learned to stop saying ‘we’ when I meant the international community. I was a full-fledged nationalist again.

But what did that mean? Today, as I write these words during the second term of the Bharatiya Janata Party government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, I see much of that noble national experiment gravely threatened by a fundamental challenge to the very essence of Indian nationalism—the ‘idea of India’ that was built up in the course of a seven-decade struggle for independence from Britain, and another seven decades of post-colonial governance that consolidated the nature and character of Independent India.

Modi’s BJP has spent its years in government contesting this remarkable and irreplaceable embodiment of the country’s essence by arguing that there can be an alternative idea of India, promoting an assortment of political, social, and cultural elements that would convert a pluralist, multi-religious democracy into a ‘Hindu rashtra’, and delegitimizing dissent through labelling disagreement with its actions and statements as ‘anti-national’. The frequent use of that term has raised the corollary—if my disagreement is anti-national, what then is truly nationalist?

—Excerpted with permission from Aleph Book Company

PRIDE, PREJUDICE & PUNDITRY:

The Essential

Shashi Tharoor

Published by

Aleph Book Company

Price Rs999; pages 574