One of the crowd-pullers at the India Art Fair 2022 in Delhi was a glaringly gaudy imp.

Around two and a half feet tall, the toy-like, earthenware figurine was perched on a platform in the booth occupied by the Mumbai-based art gallery Jhaveri Contemporary. The design was zoomorphic—the head had a snout resembling a pig, and four contorted faces, replete with teeth and gums, jutted out from the torso and limbs. On the head was a strange spiky helmet.

A dominant feature of the work—titled, matter-of-factly, ‘Figure with Spiky Crown and Pig I’—were the eyes. They were big, round and bloodshot. They were also glassy—like that of a comic-book villain, or perhaps something more sinister.

“It has got an expression that’s ambiguous,” said Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, the sculptor. “It’s either menacing, or it’s smiling and is happy, or it’s about to engage in some kind of behaviour. I am into these kinds of ambiguous expressions. From a sculptural perspective, this is a figure that sticks to the warrior archetype. It is a kind of fantastical warrior figure.”

Nithiyendran, who was born in Colombo to a Tamil father and a Dutch Burgher mother, is best known for his irreverent approach to ceramic media. Audacious in his use of colour and ornamentation, he creates mangled, toy-like figures that seduce and repel, entice and frighten. “Sometimes, subtle works that are more poetic often lose their ability to speak. In my practice, I have a sense of hyperbole and exaggeration and performance within these figures,” said Nithiyendran, who lives and works in Australia.

Quite like the imp, the 13th edition of the India Art Fair (April 28 to May 1) was wicked fun. One of the largest such events in South Asia, the fair had returned to terra firma after two years of pandemic-related restrictions. Pleasantly back was the hubbub of artists, critics, collectors, curators, museum directors and enthusiasts mingling, browsing, buying, selling and networking. Not so pleasant was the timing of the event; instead of its usual slot in the mild chill of Delhi winter—the time for long jackets and chunky knitwear—the fair had to be postponed this time to peak summer. As the mercury soared, the air conditioning in the venue would often stop working. But, art lovers, with their unflagging enthusiasm, braved the punishing heat.

“We are missing some of the old timers,” said Bhavna Kakar, founder and director of the Delhi-based art gallery Latitude 28. “But there is a good buzz around the fair and they have done a good job of inviting people. Some of our artists have done phenomenally well. The expensive pieces are taking time [to sell], but things under Rs10 lakh are moving well.”

Latitude 28’s highlight in this edition was a 72-inch, mixed-media installation in paper, watercolour, steel and wire mesh called ‘Home’ by Sudipta Das. It effectively captured the boxed-in nature of our lives during the lockdown. Comprising 1,000 paper figurines tumbling on top of each other, the inhabitants of this roofless home hold on to their suitcases and umbrella for dear life.

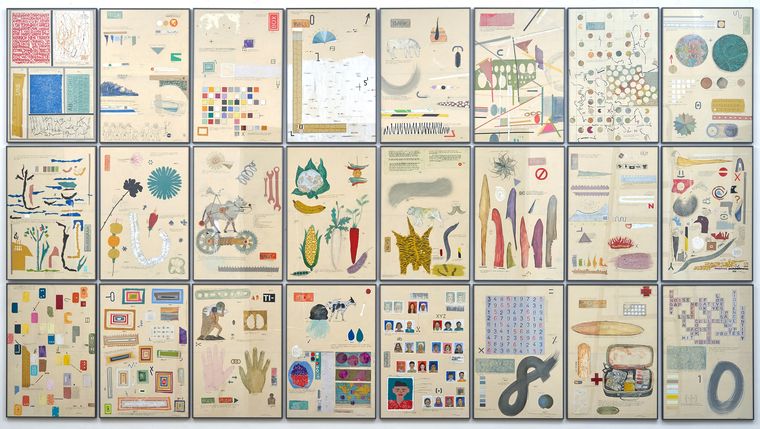

On the outer wall of the Delhi-based Vadehra Art Gallery’s booth was ‘Riverbank’, a work that propels viewers into the world of Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘The Golden Boat’. “Clouds rumbling in the sky; teeming rain/ I sit on the river bank, sad and alone/ The sheaves lie gathered, harvest has ended/ The river is swollen and fierce in its flow,” go the lines, which are transformed into a richly understated patchwork of 24 frames made of ink, acrylic, watercolour, gum tape, gift-wrap paper, barcodes and stickers, executed on silk-screened paper. ‘Riverbank’ contains within itself an entire universe of love and hate, life and philosophy, politics and insecurity.

“This body of work explores the observations and thoughts derived from a river bank,” said Shailesh B.R., the creator. “The long walks on the riverbanks of Kolkata were an insight.”

New Delhi-based artist Shailesh creates assemblages of frames that often have a scribble-book aesthetic. Sundry images and text interact on his canvas as if on a manuscript. “My studio is a kabaddi shop,” he said. “I collect the most banal objects and they go into a magic box, which I later open to create art. I saw everything on that one ghat in Kolkata, every emotion being displayed.”

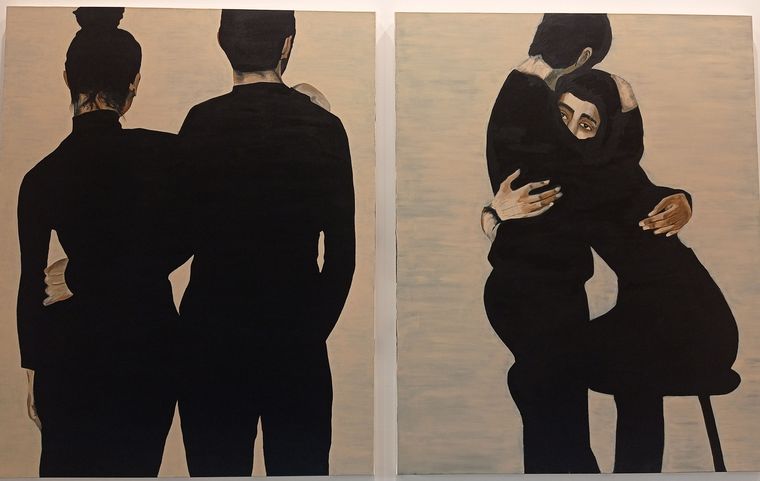

While international galleries were conspicuous by their absence, the New York-based Aicon Contemporary, which focuses on non-western art, made its presence felt. A highlight was Maya Varadaraj’s acrylic-on-canvas series ‘Absolute and Adequate Positions’. Raised in Coimbatore and Kodaikanal, Varadaraj moved to the US and forged her identity as an interdisciplinary artist after a brief stint in fashion design. While her previous work engaged with feminine narratives and representations in South Asia in a detached manner, a miscarriage made her experience womanhood at a more visceral level.

“That was the incident that sparked this new series, where I use my work to come to terms with a personal loss and also explore childhood, motherhood, and what it means to be feminine and a woman in South Asia,” said Varadaraj.

Khalil Chishtee, a Pakistan-born, New York-based artist, said South Asian artists were doing great in galleries outside their region. “But sometimes I do believe that they are not exactly ready to receive the intensity of the content that most artists from South Asia are now producing,” he said. “We have started talking about our inner lives and our reality, and that narrative is very strong; it is just not about beautiful colours or engaging forms. I think that does make a white audience a little uncomfortable.”

Two of Chishtee’s sculptures—‘Bedtime Ritual’ (a blue, plastic figure reclining with a book, wearing slippers and comfort wear) and ‘The Servant’ (cast in metal, showing a king sitting on a throne made of lyrics from the popular Pakistani patriotic song ‘Yeh watan tumhara hai’)—drew much attention by virtue of their simplicity and political resonance.

“People throw their garbage, their filth, in these trash bags. But I am storing my finest emotions in the same material. I found a trusting relationship between the two, and by doing so, I also question the hierarchy of materials artists use,” said Chishtee, who is globally well known for using trash bags and plastic as material.

There were several other surprises, including Atul Dodiya’s expansive, black-and-white Shutter paintings that combined illustrations, sculptural installation, photography and cinema, and was inspired by the life of Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani.

But not everyone seemed happy. “As far as freshness or quality of work is concerned, I find it more decorative this time—targeting architects, designers and spaces—so that it sells. I am still looking for deep-thinking art,” said art consultant Leena Namjoshi. “I wish there was more experimentation, like how Bangladeshi and Pakistani artists are showing here.”