The Adalaj ni vav never ceases to amaze B.V. Doshi.

In Gujarati, vav means stepwell, and the vav in Adalaj village near Ahmedabad is one of the most famous. A palatial subterranean structure built in the 15th century, the Adalaj ni vav (the stepwell of Adalaj) is five storeys deep, with multiple staircases leading to the bottom of a circular well. The intricately designed stepwell is a fine illustration of what Doshi says is the central purpose of architecture—giving people a sense of wonder, awe and joy. “I still get impressed [by it],” he says. “When people visit the vav, they go ‘wow!’”

One of India’s best-known architects, Doshi, 94, was recently awarded the prestigious Royal Gold Medal, given annually by the Royal Institute of British Architects in London and considered one of the world’s highest architectural honours. Simon Allford, president of the Royal Institute, personally flew to Ahmedabad to present the medal in person. The gesture underscored Doshi’s stature—he is the only Indian architect to have won the Pritzker Prize, often called the architecture Nobel.

Doshi says his career owes a lot to his two gurus—legendary architects Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, with whom he worked closely after studying architecture at Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai in the 1950s. “Corbusier and Kahn were fascinating personalities,” says Doshi. They taught him things he had not even heard of earlier. “I had never thought of what a building actually was,” he says. “Architecture, form, light, space—all of these I learnt from them.”

Doshi’s long list of works—from the academic block of IIM-Bangalore to Amdavad Ni Gufa in Ahmedabad to the Aranya low-cost housing project in Indore—draw inspiration from Corbusier and Kahn’s monumental works. Doshi says he learnt from the two gurus the nuances of heightening the value of experience in architecture. “You go to the IIM, or a temple or a mosque, and you are not educated [on the finer points of architecture]. Then, back home, you tell your parents that you can’t understand anything, but it was so beautiful,” explains Doshi. “Architecture is like taste; you have to feel it.”

Unassuming and fatherly, Doshi is at his best when he is explaining intricate points about architecture to students and lay people. He has been keeping a dairy for more than 40 years, approaching every day as a new opportunity to learn. “I work with people in my office,” he says. “Every day, you would want to discover something that gives you satisfaction.”

His routine, however, took a hit during the pandemic. His morning visits to his studio, Sangath—a set of terrazzo-covered buildings with vaulted roofs of varying heights, where Doshi “learns, unlearns and relearns”—became few and far between. Because of the restrictions, he was mostly confined to his bungalow in Ahmedabad, where he lives with his wife, Kamla. Since the pandemic began, though, their three daughters—Tejal, Radhika and Manisha—have been taking turns (“Ten days each,” says Radhika) to be with their parents.

An early riser, Doshi begins his day by practising pranayama and listening to jazz or Indian classical music. “We wake up to the sound of music in the house,” says Radhika.

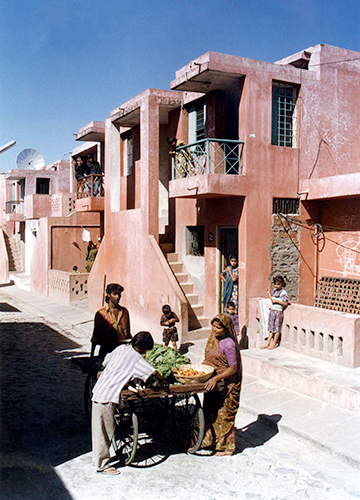

How did he feel when he was presented the Royal Gold Medal? “Thrilled,” says Doshi. “I also slept well.” The medal, he says, is the result of his overarching aspiration to do the good work. That is why among all his initiatives, the Aranya housing project remains his favourite. “To the poorest of the poor, I gave a place to live, and a community to thrive and celebrate together,” he says.

It is not just buildings that Doshi has built. He has a formidable reputation as an educator and institution builder. He co-founded, among others, the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, and the Kanoria Centre for Arts, both of them in Ahmedabad.

Renowned architect Rajagopalan Palamadai fondly remembers Doshi’s fascinating ability to help students like him mould themselves. “He never spoon-feeds,” says Palamadai, recalling the day when Doshi asked him to explain a design after assuming that the teacher was a blind man. It was a brilliant device to make the architect sensitive to every detail in the design. “You will have to talk about colours, textures, lighting, and so on,” says Palamadai.

Doshi sees architecture as a celebration of life—something, he says, is fast disappearing. Today, according to him, architecture is all about fulfilling a certain set of concrete functions and obligations. Indian architecture, he says, has come to resemble products—a product is made for a purpose, and the purpose is defined. So architecture, in that sense, is no longer about celebrating life or imparting a sense of wonder. It has minimal use, and is mostly perfunctory.

What about the Central Vista project, arguably India’s most prestigious architectural initiative in decades? Doshi, who is not currently involved in any project, says he did not want to comment.

According to him, Indian architecture, when compared with the state of architecture abroad, had “no strength”. “Architecture has become a mere product to be brought home and then discarded when the work is done,” he says. “There is no relationship, no memories, and there are no stories.”