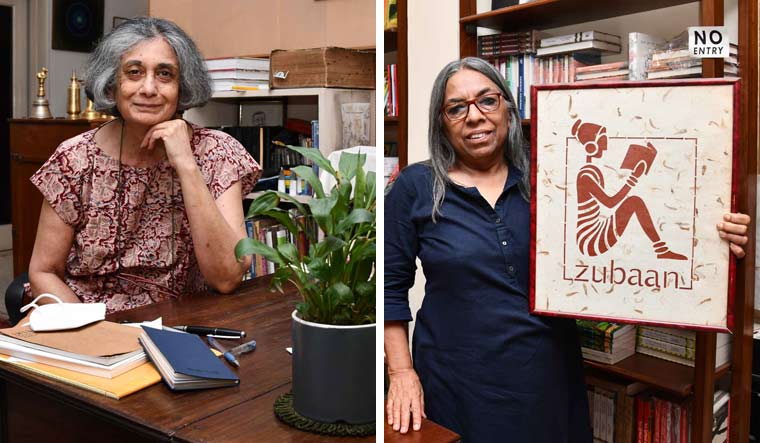

It is a rainswept Monday afternoon in the capital. Pools of water reflect the green. Ritu Menon—feminist, writer, editor and publisher—stands in her home filled with books, and two cats that stay outside. It has been a giddy week for publishing in India with Geetanjali Shree winning the International Booker for her book, Tomb of Sand. One half of Kali for Women—a publishing house that embarked on translation before it became a buzz-word—Menon is very much a pioneer in the industry. Across the road, in a tiny red book-lined office in Shahpur Jat, is the other half of the original team: Urvashi Butalia.

Their link with the International Booker is tenuous. It is at best a story that is likely to get lost in the six degrees of separation. In Indian publishing, however, it is often closer to three. But after the win, this link should perhaps be centre-stage. Mai, Shree’s first book to be translated into English, was published by Kali. (It is this translation which made Deborah Smith, Shree’s publisher in the UK, determined to publish her.)

Smith is not the only one. Much before the big publishers signed up authors who have now become very much part of the English landscape, it was independent publishers who first took the risk. They brought into English names that have now become common, like Ismat Chughtai, Salma, Bama and Qurratulain Hyder.

If Shree’s big win has changed the landscape for Indian translations—and certainly brought into the limelight the sheer wealth of writing beyond English—it is also very much a moment to realise, and cherish, the independent publisher. In Hindi, it was Raj Kamal Prakashan, independent as language publishers tend to be. In the UK, Tomb of Sand was published by Tilted Axis, the name itself giving away the purpose of the press. Set up with the money Smith won for her translation of The Vegetarian, the publishing house aims to make translation more inclusive. Smith’s mission is a perfect example of what has fuelled and sustained translation for years—the small independent publisher.

This is a league of extraordinary publishers, survivors and readers driven by passion. There is Naveen Kishore of Seagull Books in Kolkata. Gentle, enthusiastic and gentlemanly, Kishore is ever the optimist. “He has hope that people read,” says Bishan Samaddar of Seagull. Courtesy Seagull, Mahasweta Devi’s work is now available in Chinese. Then there is Mandira Sen of Stree, also in Kolkata—the first publisher of Manoranjan Byapari, who is now very much an established author. Rakesh Khanna and his wife, Rashmi Ruth Devadasan, of Blaft in Chennai have gone beyond the classics to find mass sellers for English readers. “It is a different trip,” says Khanna. “Translations in English only tend to be of the classics. The mass market book finds no mention. There has to be something in it if everyone is reading it.” There are others like Navayana that is focused on caste, Yoda Press, Speaking Tiger and Niyogi Books. “Daisy Rockwell (who translated Tomb of Sand) got a translation grant from Pen England,” says Menon. “Without which that translation would not have been possible. Without which Tilted Axis would not have been able to afford to pay her. It is important that we recognise the economics of this, which is critical.”

The economics is usually against the independent publisher. But their role—especially internationally—cannot be ignored. Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, too, was made eligible for the Booker by an independent publisher. Five out of the six books nominated for the International Booker were printed by independent publishers. Their role in shaping the landscape of literature is often ignored. In India, they were the first to translate a diversity of Indian languages into English. In the harsh terrain of publishing, they plug the gaps left by international publishers, often finding a gem, holding it up, and bringing it to the world.

“We started by making a commitment to translation,” says Butalia. “We felt that if we were going to publish women’s voices, we could not just restrict it to women like us. As a publisher, we have a responsibility not to just do the same old. It is easy to remain in our comfort zone. To do the kind of stuff that readers will pick up. In some ways, your responsibility is to expand the horizons not for the readers, but for the writers.”

Translations in India—even with the big publishing houses jumping into the fray—are very much a labour of love. (For years, translators were ignored.) The road has been paved by many pioneers. Jawarharlal Nehru realised their importance and as a result, the translation programmes of the Sahitya Akademi and the National Book Trust have been quietly and steadily ensuring that writers across languages read each other. There was Macmillan—the most profit-driven company that had a huge translation programme headed by Mini Krishnan, supported by a grant, who has been very much part of the story.

“It can’t be done with a ‘for profit’ motive,” says Arunava Sinha, who has translated over 71 books, including the only translated bestseller in English—Chowringhee by Sankar in 2000. It sold 25,000 copies. Translations are never about the money, reiterates Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharjee of Niyogi Books. “If we sell 1,000 copies of a book we are thrilled,” he says.

The translation project—much before it became a moment—has been what reading is all about: finding other worlds. “It is largely serendipity,” says Krishnan, who has been at the helm of finding and publishing dalit writers. “You publish one and then, people recommend others.” And often ones that go beyond just fiction. Arpita Das of Yoda Press is one of the most feisty and adventurous publishers who pushes boundaries and genres with each book. Her focus is to plug the holes left by mainstream publishing, especially in non-fiction. “I am hopeful that translations of non-fiction and poetry, too, will get support and attention now,” she says.

But more than anything else, it is about faith, flying blind and pure luck. “It is a drug,” says Sinha, who is now part of the Ashoka Centre for Translation to encourage translations across languages and make it sustainable. “Once you get addicted, you can’t stop.” If Salman Rushdie’s win announced the arrival of Indian English on the world stage—and later, Roy cemented it with her feat that she had never written before—Shree’s win is very much a moment for Indian languages in English. It is a moment, but it is still years from being a movement.