Hamza also had troubles on his mind. On many occasions he walked the shore road in the direction of the house where he once lived. He was there for several years, from when he was no more than a child taken away from his first home to when he ran away to join the schutztruppe.

Hamza is the protagonist of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s latest novel, Afterlives (2020), about life in an unnamed coastal town in East Africa. It is set in the 1900s at the end of the German rule, when the British are about to take over. Hamza is fed up with life in his village and runs away to join the schutztruppe or the German army. What happens when he returns as a hardened ex-soldier forms the heart of the book.

It is a poignant story written in Gurnah’s usual understated style. He does not intellectualise his subject, nor does he use any kind of showiness in his writing. But the themes are familiar―a return to home, a desire for belonging, the excesses of colonialism, both the claustrophobia and the charm of small-town life, the hardships of poverty…. As his long-time editor Alexandra Pringle said at the Jaipur Literature Festival, where Gurnah was the keynote speaker, “His stories are about small people set against large pieces of history.”

In many ways, for Gurnah, writing is an act of resistance, against history being re-written from the victor’s perspective. Just like Hamza returning to his village, Gurnah describes walking through the streets of the town he grew up in, long after he had left Zanzibar for England after the revolution of 1964. “[I] saw the degradation of things and places and people, who live on, grizzled and toothless, and in fear of losing the memory of the past,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech. “It became necessary to make an effort to preserve that memory, to write about what was there, to retrieve the moments and the stories people lived by and through which they understood themselves. It was necessary to write of the persecutions and cruelties which the self-congratulations of our rulers sought to wipe from our memory.”

Guest of honour: Gurnah at the Jaipur Literature Festival with festival directors William Dalrymple and Namita Gokhale | Sanjay Ahlawat

Guest of honour: Gurnah at the Jaipur Literature Festival with festival directors William Dalrymple and Namita Gokhale | Sanjay Ahlawat

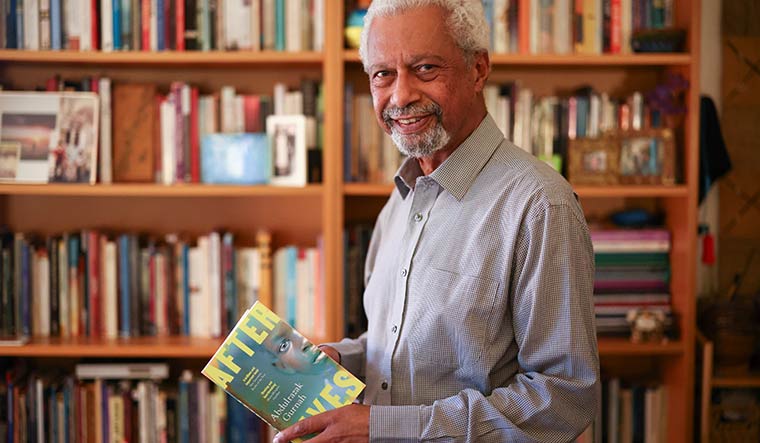

Much like his writing, Gurnah has a straightforwardness about him. He does not want to trim the truth, about himself or his stories, but neither does he want to amplify it for better effect. He is not afraid of coming across as mundane. Eloquence is not a compulsion. With Gurnah, what you see is what you get.

“For me, getting to the UK at the age [of 18] was filled with a sense of ‘What have I done?’,” he said at the JLF. “What have I landed myself into as a young, untravelled, unskilled and poor lad in this country that did not want me? The need to understand the feeling of loss, hostility, adventure and newness, and work all that out is what started me writing. It was not intended for anyone to see. It was just for me. There was a kind of pleasure in putting down all that self-pity and misery.”

He remembers the monsoon winds to the island of Zanzibar travelling directly across the Indian Ocean. As a result, sailors from western India, southern Arabia, Somalia and various other places landed in Zanzibar when the northeast monsoons blew its way. Some stayed, others did not. But they left behind a beautifully complex mosaic of cultures, traditions and languages on the east coast of Africa. As a child, he remembers listening to tarab (a music genre popular in Tanzania and Kenya), Indian songs and Elvis Presley, and “packed Saturday morning cinemas in Zanzibar… all of us laughing and cheering as Tarzan outwitted and outfoxed another greasy African nasty….”

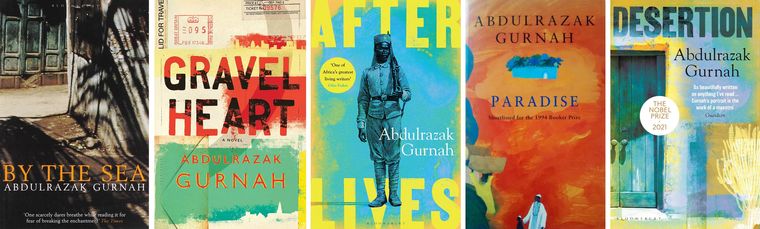

There was an innocence about his childhood, he says, because he knew so little. “It just felt so safe,” he says. “It is only later that you begin to see how fortunate you were to be in a place like Zanzibar, and to have enough to eat, friends to play with…. Not everybody had those things.” The acute sense of loss he felt in England and the peculiar experience of exile are splayed across most of his novels, from his first, Memories of Departure (1987), about a 15-year-old boy who seeks to escape the violence and poverty of his village, to Desertion (2005), about an Englishman who falls in love with an African woman. But his breakthrough work is considered to be the Booker-shortlisted Paradise (1994), about a 12-year-old boy sold to a trader by his father. The idea for the book struck him when he returned to Zanzibar in 1984.

“There was an amnesty then, and we were allowed to go back if we wanted to, so I took that opportunity,” he says. “There was a leak in the roof of the flat I was then living in. We managed to persuade the insurance company to pay £600 to have this repaired, so I stuffed some newspapers into the leak and used the money to buy a ticket to Zanzibar.” One day, in his native town, he observed his father walking to the mosque and thought how old he looked. Gurnah began imagining how his life would have been in the early 1900s, when he was just a boy and European colonialism was taking hold in East Africa.

“What would it have been like for someone like him, seeing the world changing around him, seeing strangers coming and taking control of his society and culture, and the way he did things? That was the idea behind Paradise―European colonialism and its consequences,” he says.

In each of his novels, he has not departed from familiar themes, but has only refined them with a style that is refreshingly sparse. “I only write what I know,” he says. “If you asked me to write about the life of a millionaire, I would not be able to.” And when what he writes is right, it is almost like he can shut his eyes and hear it like a piece of music.