A big, black dot on a white wall of his school became his mind’s anchor.

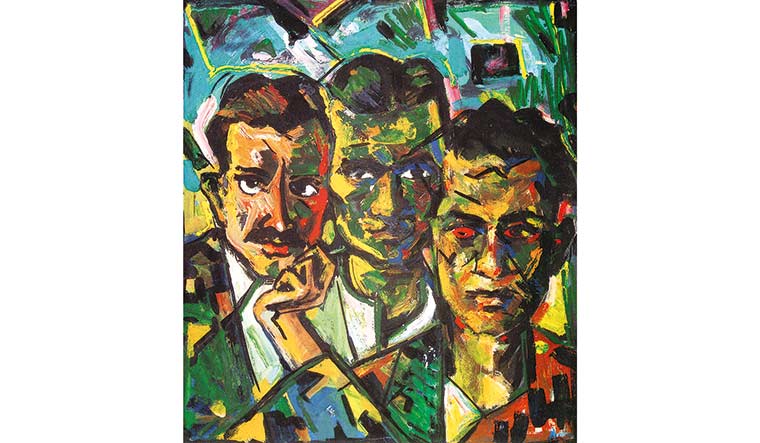

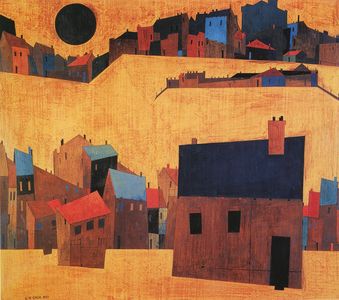

Sayed Haider Raza had a wanderer’s soul since childhood; his mind never stayed put. For that matter, neither did his feet―it took him places, from the Gond forest in Madhya Pradesh to Gorbio in France and back to India. But his primary schoolteacher, Nandlalji Jharia, just wanted to momentarily still his mind and instil focus. And, that is why he drew that black dot on the wall. Raza was all of eight and the true meaning of that dot was lost on him then. But it always came back to him, when he was in what was then Bombay (his J.J. School of Arts days) and later during his sojourn in France. It finally broke free from his mind’s cage and landed onto his canvas in the form of ‘Bindu’―his leitmotif or as Raza called it “the very backbone supporting my body of work”. After his return to India―he lived in New Delhi―his work was largely about variations of ‘Bindu’. Life and, perhaps, his work had come full circle.

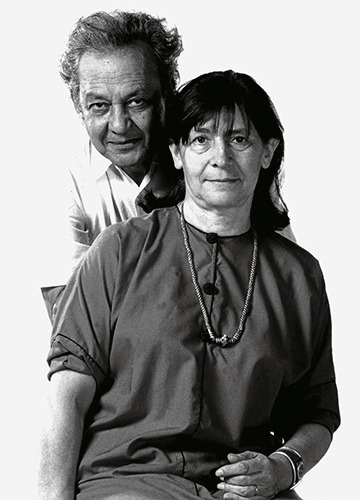

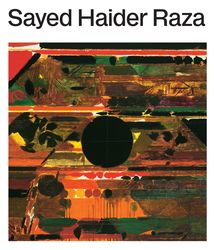

The childhood anecdote about ‘Bindu’ finds mention in most of the initial essays in Sayed Haider Raza, edited by Raza’s poet friend Ashok Vajpeyi and published by Mapin Publishing with The Raza Foundation. Commemorating Raza’s 100th birth anniversary, the book starts with six essays, followed by notes by Raza and the letters he wrote to his second wife, artist Janine Mongillat, translated from French to English. It also has extracts and essays by eminent critics on Raza and snapshots of pages from Raza’s notebooks and of letters from other artists, ending with a catalogue of Raza’s works. But, to call the book a mere catalogue is like reducing Raza to just an artist.

He was so much more. An avid reader, he devoured the writings of Rainer Maria Rilke, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus and found inspiration in the poetry of Kabir, Mirza Ghalib and Faiz Ahmad Faiz. Poetry naturally flowed into his art. As Vajpeyi, life and managing trustee of The Raza Foundation, writes, “he is perhaps the only modern artist in India, in the world even, who has inscribed in nearly a hundred canvases lines and words of Sanskrit, Hindi and Urdu poetry in Devanagari script”. One of Raza’s works―‘Maa’ (1981)―has an inscription in Hindi, “Maa, lautkar jab aaunga, kya laaunga [Mother, when I return home, what shall I bring]?” That is a line from Vajpeyi’s poem for his mother, which Raza adeptly used for motherland. And, just like in his art, there was poetry in his writing, too. ‘I Will Bring My Time’, the section dedicated to his love letters to his wife, has a side note by him: “I greeted the sun and asked it to smile at you.” That is French kiss in poetry for you!

There is some overlapping of information in the book, but that is expected. One of the essays though, by art historian Ashvin E. Rajagopalan, does shed some light on Raza in the 1940s. As Partition divided a country, it divided his family, too―everyone, except him, his mother and first wife, left for Pakistan. He also worked as a designer in a commercial printing and design studio to sustain himself and his family. His mother died later, and he and his wife―divorced―went their separate ways, she to Pakistan and he to Paris.

While Raza’s works were restricted to the contours of a canvas, it was never bound to form or medium―he moved from landscapes and geometrical forms to abstract shapes, and from gouache to oils and acrylic. The book does not just present his works but also the person behind them, who was not limited by language (he knew four), to places or in faith (a devout Muslim, he visited temples and churches).

So you may own a Raza, but you will never truly own him.

SAYED HAIDER RAZA

Edited by Ashok Vajpeyi

Published by Mapin Publishing with The Raza Foundation

Pages: 296; price: Rs3,500