Tamil writer Perumal Murugan once wrote his own “literary obituary”. “The author in Perumal Murugan is dead. As he is no God, he is not going to resurrect himself. He also has no faith in rebirth. An ordinary teacher, he will live as P. Murugan. Leave him alone,” he wrote on Facebook.

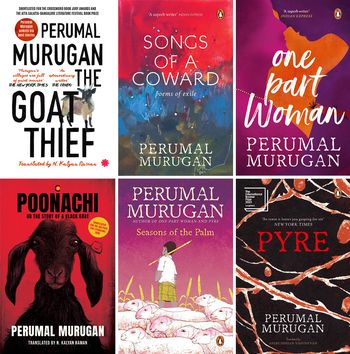

It all began with the controversy that broke out after the publication of his book Madhorubagan or One Part Woman in 2010―a raw and poignant story about a custom practised in western Tamil Nadu, where childless women can have sex with any stranger one night in a year, during a temple festival. That night, the taboos around sex are kept aside. The book became controversial five years later, when Hindu activists called out the author for insulting women and the temple tradition. The book was banned, and protests erupted all over Tamil Nadu. Murugan quit writing after this and went into self-imposed exile. But a year later, when the court gave him a clean chit, he took up his pen again.

Seven years later, his novel, Pyre, has become the first Tamil book to feature in the International Booker Prize long-list. The winning title will be announced on May 23. Translated into English by Aniruddhan Vasudevan, Pyre is set in a Tamil village in the 1980s. It tells of the violence that erupts when an inter-caste couple elopes from their village. “Perumal Murugan is a great anatomist of power and, in particular, of the deep, deforming rot of caste hatred and violence,” stated the Booker judges.

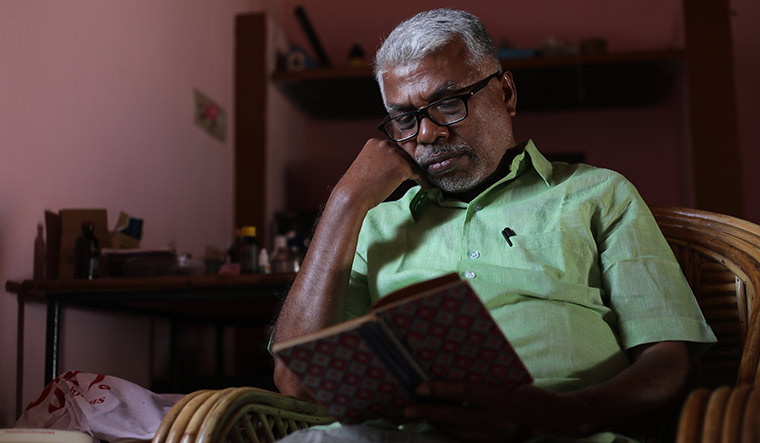

Murugan, 56, is a behemoth of Tamil literature, having written 10 novels, five collections of short stories and four anthologies of poetry. His work delves into life in western Tamil Nadu, popularly known as the Kongu region, where he is from. He is intimately familiar with its customs and dialect. Whether it is the coconut fronds wailing in the moonlight, couples making love in a hay barn or fields of millet stalks dancing in the wind, Murugan brings alive the place with a lilting lyricism. With Pyre, he takes the dusty small-towns of Kongu and the quirks of its people to the outside world. “It is historic that a Tamil novel has reached this place,” he tells THE WEEK from his home in Namakkal. “I am delighted. It is an acknowledgement of Tamil literature.”

Hailing from an agricultural family, there was only one reason why Murugan and his siblings were sent to school―the nutritious mid-day meal for primary school students. However, his parents had one condition: If they failed in a class, they had to quit school and help them in the farm. Murugan loved his classes as they satiated his hunger to read and write. He was the only one in his family to finish school. As his parents were not able to afford newspapers or books, Murugan would lap up everything in his textbooks. There were days when he would read every word on the newspaper in which the groceries were wrapped.

The first book he bought was in 1978-79, when he ran away from home after a fight with his parents. At his friend’s house in Salem, he was advised to return. Right before boarding the bus back home, he purchased a book from the bus station―a collection of poems by Namakkal Kavignar. “I bought it for Rs10,” he remembers. “I still have that book.” Later, when he entered his teens, he began buying books from publishing houses through the Value Payable Post (VPP) scheme. But safeguarding these books was the difficult part. If his mother found them, she would sell them to buy dates or vada.” I would have to hide them in places where my mother would not look,” he says with a smile.

His first story―Nigazhvu (An Incident)―was about strangers staring at him when he and his friend visited a teacher’s home. It was published in August 1988 in Kanaiyazhi, a popular literary magazine headed by Asokamitran, a pioneer of modern Tamil literature. “It was a great honour for my writing,” says Murugan. Today, he has been teaching Tamil literature for 25 years. Most of his students come from a rural background. He himself is the inspiration for many of them. Thirty-two of them wrote a book on him titled Yengal Ayya (Our Teacher). In return, he wrote a book on them titled Manathil Nirkkum Maanavargal (Students Who Remain in my Mind).

If he had not been thrust into the limelight, the soft-spoken Murugan might have preferred to remain in the shadows. He has never promoted himself for celebrity status. Even when protests broke over his book, he did not get combative. He simply kept his head down and stuck to his daily routine. When he returned to writing after the controversy, he could not get the flow initially. Then he began writing Poonachi allathu Oru Vellattin Kathai (Poonachi or the Story of a Black Goat) and everything came back in a rush. “When I realised I had not lost anything, it was a moment of extreme happiness,” he says. Within a short span he penned 200 poems, which reignited his love for poetry and made him realise how much the literary form meant to him. Putting the controversy firmly behind him, he published the collection of poetry, Oru Kozhaiyin Padalgal (Songs of a Coward), in 2017. “This collection of poems was an emotional outburst that made me resurrect myself in the literary world,” says Murugan. The man who was resurrected might have been slightly more weathered. But his writing bore the sheen of a land reborn after a storm.