When Jubilee’s Nilofer, played by Wamiqa Gabbi in the 2023 web series, is brought to a shabby kotha in a newly independent India, she resists, asking to be taken to a better one. She finally escapes from the clutches of the ‘madam’ and goes on to become an actor in Bombay. Nilofer’s transition from a tawaif in British India to an actor in independent India perfectly captures the death of the tawaif culture that came about with the British rule and India’s subsequent independence.

This forgotten culture is the premise of filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s OTT magnum opus Heeramandi. The upcoming series narrates the stories of three generations of tawaifs living in Heera Mandi in pre-independence Pakistan’s Lahore. It is not as if tawaifs never had a screen presence―they have been immortalised by leading actors like Madhubala in Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Meena Kumari (Pakeezah, 1972) and Rekha and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan (Umrao Jaan, 1981 and 2006). But there has been a renewed interest in the life and times of tawaifs, not just on screen but off it, too.

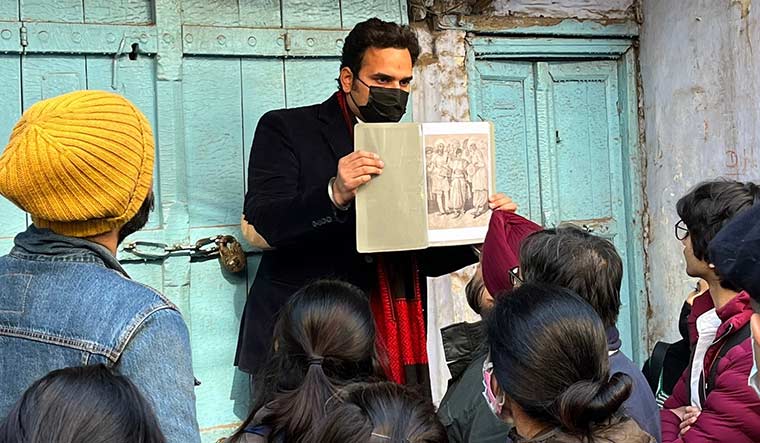

Walk down memory lane: Gaurav Sharma conducts heritage walks around former tawaif colonies in Old Delhi.

Walk down memory lane: Gaurav Sharma conducts heritage walks around former tawaif colonies in Old Delhi.

Unlike popular perception though, tawaifs were not prostitutes. According to Saba Dewan, author of Tawaifnama (2019), tawaifs were women highly skilled in the arts, music and dance who also offered sex, but always consensual―they could choose their lovers. They played an important role in preserving art forms, from classical musical strains like dadras, thumris, and ghazals to dance forms like kathak. They were wealthy, owned properties and enjoyed the patronage of the upper class and the creative community. Their origins can be traced to the period of renaissance (14th-17th century) where courtesans―women who stayed in royal courts―offered entertainment and companionship to aristocratic men. Be it in Greece, Rome or closer home, courtesans became women of importance in the society. “They would say men weren’t cultivated enough if they didn’t frequent a kotha,” said Dewan. “But the reality was that in the 19th century, kothas were sites of artistic cultivation with highly trained dancers, musicians, poets and writers. There were ustads and musicians put up there and kothas were cultural hubs.”

But in a colonial world, the tawaif culture was deeply stigmatised and lost patronage, with public morality being preached. “‘The white man’s burden’ was to cleanse the society of such ‘fallen women’ and to ‘control loose men’,” said Dewan. What further put a stop to the tawaif culture was the Contagious Diseases Act of 1868 that formalised detaining and checking of ‘diseased’ women to prevent the spread of venereal diseases and the Cantonment Act of 1895 that outlawed any official approval of prostitution in cantonments.

Also, the need for a tawaif was diminishing in a fast-changing world, said Dewan. By the late 19th century, middle-class women were educated and could provide companionship to men rather than just being caregivers. Furthermore, entertainment was now also found in cinema and in clubs. Dance bars, she added, were “a manifestation of the decline of the tawaif culture and the dance bars were trying to evoke a filmi image of tawaif girls. Girls related to former tawaifs also worked in bars”. That is when the boundaries between a tawaif and a sex worker were blurred, explained Dewan, as the former took to sex work for financial support. However, back in the days when kothas and tawaifs thrived, there was a clear difference between a tawaif and a sex worker.

Manish Gaekwad, author and senior manager (creative), Red Chillies Entertainment, said his mother, a former tawaif, would get furious when anyone confused them with sex workers. “We don’t do that work,” she would say. He also does not agree with the glorification of the tawaif culture in films. The first look of Bhansali’s Heeramandi shows women dressed and decked in gold. Even his Chandramukhi in Devdas (2002) had a similar touch. “Not all tawaifs were as glamorous as Bhansali’s are,” said Gaekwad, who wrote the screenplay for the 2020 web series She and was the script consultant for the 2022 film Badhaai Do. “Some lived in small and scruffy kothas.” The days were spent in riyaaz (practice) and kathak training and the nights were spent entertaining patrons, he added.

Gaekwad grew up in a kotha, and remembers a beautiful world engulfed in perfume, costumes, music and dance. As he grew up, the hushed words and silences around him made him realise that there was something unacceptable about his mother’s profession. “I was called the son of a whore,” he said. “When I was sent to a boarding school, I always told everyone my mother was a dancer, which she was, and nobody had to know more than that.”

Most tawaifs of the time earned well, as the income was unaccounted for, and sent their children to boarding schools to give them a better future. However, with liberalisation and opening of bars, the kotha culture became a closed-door affair. “I don’t want to blame Manmohan Singh here (who is credited with liberalising the Indian economy as finance minister),” said Gaekwad, chuckling.

In 2018, Gaekwad wrote about his mother’s journey on Twitter and in newspaper columns, which landed him a book deal. He has published two books so far―Lean Days (2018) and The Last Courtesan (2023). His second book is a first-person account of his mother’s story. His next book, which comes out next year, is based on his growing up years in a kotha.

Stories of tawaifs are finding their place not just in books and scripts. Gaurav Sharma, who teaches Indian Art History at NIFT Delhi and conducts heritage walks, has observed a growing interest from middle-aged people and students, especially women. His walks are centred around former tawaif colonies in Old Delhi. Once the Mughals shifted their capital from Agra to Delhi, he said, the tawaif culture, too, spread across Old Delhi. Only a few remnants remain today like the Randi Ka Masjid in Old Delhi that was constructed in a tawaif’s honour. “I carry photos for people to visualise how the kothas were as none of them exist today,” said Sharma. While narrating the history, he makes sure to avoid the use of certain words as they have been misconstrued over the years. Mujra, for instance, was not necessarily attached to dance but was a salutation, he said.

Dewan said that the current conversations around tawaifs were helping address a crucial silence in women’s history. “It is about recovering lost history,” she said. “Tawaifs should get due credit for preserving art and culture and dance forms generation after generation.”