How do you make the casting czar of Bollywood ecstatic in a moment and jittery in the next? First, offer him Jawan (2023), and then slip in that it will be helmed by Atlee, who is best known for his Tamil hits.

When Mukesh Chhabra was asked to consult Atlee, he got nervous. Not because he had to cast more than 150 people, but more because the relationship between casting directors and filmmakers is quite delicate. And, it is in the initial meetings that one figures out whether the pairing will work. Also, down south, there are no casting directors; the filmmakers do the casting. “But Atlee understood the strength of a casting director,” says Chhabra, “and the other advantage for me was that Bollywood was very new to Atlee.” It took him almost a month to understand Atlee. “When you are working with a director like Atlee who is not from here, especially when he has never done a Hindi film, it takes a while to just come around to his way of thinking,” he explains. “I figured that to crack this commercial film, we have to fill it up with a great ensemble cast, with new and established faces. I had earlier worked on big films like PK (2014), Sanju (2018), Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015)... this was very different in terms of scale and imagination. I had eight assistants on this film, and each focused on managing groups of ten actors.”

Chhabra was impressed by Atlee’s ability to gauge an actor from his or her photograph. “Somehow, he never saw an audition,” he says. “He would simply see the face and know whether this person could act or not. That’s how we found Aaliyah Qureishi, Sanjeeta (Bhattacharya), Lehar (Khan) and Riddhi Dogra.” And, it paid off―Jawan became the second-highest grossing Bollywood film.

In an industry that revolves around actors and directors, the work of a casting director rarely gets acknowledged, let alone appreciated. Chhabra would know. Like others in the periphery of filmmaking, he would find his name buried in the end credits. And then Anurag Kashyap’s Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) happened. He cast 384 people for it and got his first opening credit as casting director. He was 26 then, with neither a big team nor a plush office. There was no concept of a casting director then; the only other casting director apart from him was Honey Trehan, who worked with Vishal Bhardwaj.

Today, with more than 300 films to his credit, Chhabra has close to a hundred people working for him at his three-storeyed office in Versova, Mumbai. He was the first to go corporate with the Mukesh Chhabra Casting Company (MCCC). His office has now become a landmark. Even the rickshaw driver asks, “Do you want to go to Mukesh Chhabra for acting?” A valid query, considering the number of people waiting outside his office. His team, mostly Gen-Zers, shoot a video of the wannabe actors with a handycam. The artistes are asked to hold a slate with their name, age, languages spoken, experience, hobbies, mobile number and place of residence written on it for the camera and give their credentials in a minute. After that, it is a long, long wait. All that information goes into a database. If a suitable role comes up, hundreds and sometimes thousands of candidates are called in for short auditions. A handful of them are shortlisted and only one or two make the cut. There are folders of real-life paanwallahs, rickshaw drivers, transgenders and children, too. The supporting cast is almost always made up of real people, says Chhabra. “That way it is more convincing,” he says.

Mumbaikar Arya Keralia, 21, is fluent in Gujarati, Hindi and English and believes that he will be “set” if Chhabra casts him. Lean, fair, with average height and gelled hair, he is wearing a tee that hugs him like cling-wrap, accentuating his abs and toned body. He has written his details on the slate and is waiting to be called in. “There is no point in approaching a director directly,” he says, “nobody entertains. This is the proper channel and I really hope they call me for an audition soon.”

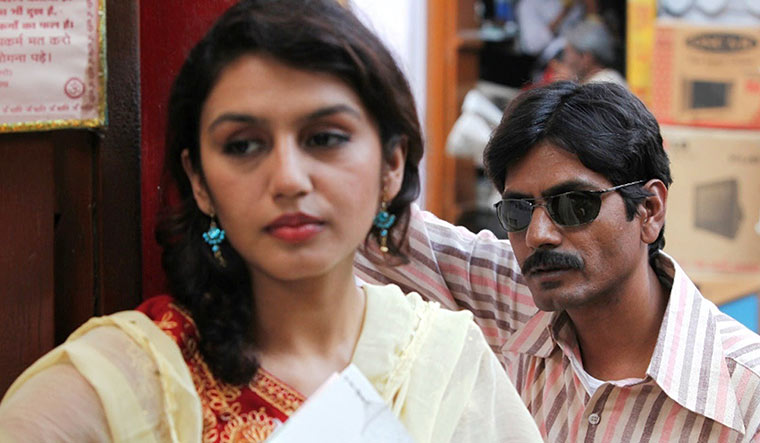

A still from Gangs of Wasseypur, in which Chhabra got opening credit as casting director.

A still from Gangs of Wasseypur, in which Chhabra got opening credit as casting director.

In a business that runs on the currency of names, Chhabra’s now has demonstrable value, able to attract talent. But he is aware that fame can corrupt. “Thanks to my parents, I don’t really take success seriously,” he says. “Every day, I am insecure about my next casting.”

Chhabra also credits his middle-class upbringing for his ability to empathise with upcoming artistes. His father introduced him to theatre when he was a teenager, just to distract him from pursuing cricket―the kit was expensive and training beyond their means. “He said, ‘You watch plays…. They won’t charge you a bomb, and each time you will learn something.’” Summer workshops at the National School of Drama in his teens and a diploma in acting years later helped him understand the nuances of emoting. But theatre made him want to, not act, but learn the ropes of the trade. That is how he began assisting a filmmaker and eventually got into casting. His first work as a casting director was for Richie Mehta’s Amal (2007).

Talent spotting: Fatima Sana Shaikh in Dangal and Sharib Hashmi in The Family Man (below) were picked by Chhabra.

Talent spotting: Fatima Sana Shaikh in Dangal and Sharib Hashmi in The Family Man (below) were picked by Chhabra.

Done right, casting is an invisible act. The choice of an actor should seem obvious in retrospect. So how does he spot talent? “Instinct,” he says. “I also follow my director’s vision.” He travels extensively across the country, scouting new talent in acting and dance schools. “The more newcomers you meet, the better it is for you,” he says. “You get more work.” It does not take much to impress Chhabra. “Be as normal as possible,” he says. “I don’t believe in fair and muscular, and whoever tries to impress me with beauty will be out of my life. If you are a good actor, a passport-size photo is enough. People will get bored of your beauty after half hour. But they will remember your acting forever.”

To make his point, he lists the names of Rajkummar Rao, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Vicky Kaushal, Jaideep Ahlawat, Vijay Varma, Pankaj Tripathi, Manoj Bajpayee, Mrunal Thakur, Sanya Malhotra and Ayushmann Khurrana. Some of them made it to the big screen, all thanks to him. And, their gratitude is displayed on his office walls. For instance, Vijay Varma, who was recently seen in Jaane Jaan, wrote, “I started with you; I will grow with you.” There are also notes of thanks from Fatima Sana Shaikh, whom he introduced in Dangal (2016), and Mrunal Thakur, whom he cast in Super 30 (2019), her first film, and Jersey (2022). Thakur was shortlisted for Dangal, but lost out, only to be cast later. Chhabra noticed Sharib Hashmi at a screening in Filmistan Studios and decided that he would cast him soon. That is how The Family Man’s (series; 2019) Srikant Tiwari (Bajpayee) got his friend. How does he remember so many faces? “I have a strong memory,” he says. “No actor goes waste because every face is important. I keep watching plays and films. And if I meet you once, I will never forget.”

But do casting directors have the final say? Depends on the filmmaker. “With Hansal Mehta, Anubhav Sinha, Sudhir Mishra, Nitesh Tiwari, Raj and DK, my advice is taken very seriously,” he says. “I am part of every discussion. I am the first one they consult after the script is ready.”

Filmmaker Imtiaz Ali commends Chhabra for the kind of talent he has brought into the industry. “It is said that thousands of boys and girls land in Mumbai each day trying to become actors,” he says. “It is unimaginable how he deals with a large percentage of those thousands and deals with them well and continues to provide for them a great opportunity and us filmmakers with great talent.” Ali adds that the first credit for casting director in his films came with Love Aaj Kal (2009) and it was for Chhabra. “Before he came into his own as a casting director, there were very few character artistes,” says Ali. “But after he came in and because of him, talented and skilled actors from theatre came into cinema.”

Hansal Mehta, too, values what Chhabra brings to the table. It was thanks to Chhabra that Mehta found Rajkummar Rao, whom he has cast in several films, including Shahid (2012) and Aligarh (2015).

Like Rao, most newcomers that Chhabra has launched are outsiders. “I do not believe in the star kid concept; it is talent that matters,” he asserts. “Sanya Malhotra is one great example. I have cast very few star kids because I think they do not need me. But I really think Ibrahim Ali Khan (Saif Ali Khan’s son) is going to make it really big. I will 100 per cent cast him. Suhana Khan (Shah Rukh Khan’s daughter), too, will go places. I think it is our judgment that is wrong, not their talent.”

Cracking auditions is not easy. Ask Gagandev Riar, a theatre actor who had to nail Abdul Karim Telgi’s persona for Scam 2003: The Telgi Story (series; 2023). He failed his first audition, but returned for a second one three days later. “In those three days, I think he immersed himself into the life and times of Telgi,” recalls Chhabra. “His prep was so good that I could not see beyond him; he fit the part perfectly.” But not everyone takes rejection sportingly―the broken windscreen of Chhabra’s car would bear testimony.

What does life look like right now? “In progress,” he replies, grinning. Chhabra lives with his father; his mother died recently. His mother was his “most avid cheerleader”―they had even planned a foreign trip together just before her death. His office has her presence, in portraits and life-size photographs.

Having been in Bollywood for close to 16 years now, Chhabra now wants to establish his footprint in Hollywood. “But not as a pawn who is just casting for small, tidbit roles,” he says. “I will go only and only if they offer me an opportunity to cast for an entire film.” And what about marriage? “I am only 40 now,” he says, smiling, “there is plenty of time left.”