Interview/ Abha Narain Lambah,conservation architect

When Abha Narain Lambah came to Mumbai as a young architect, the first building she prepared a conservation plan for was the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room in Kala Ghoda, an area known for its Victorian, Gothic and art deco buildings. That time they did not have enough funds, so she had to turn her attention instead to the India Habitat Centre in Delhi, which was the first building she restored in 1993.

The allure of the David Sassoon library, which turns 157 this year, remained though, and she finally got her chance in 2022, when the library signed an MoU with the JSW Foundation to restore and conserve it. The first thing she felt had to go was the RCC slab that replaced the main roof of the building. “We now have a sloping roof, exactly the way it was in the original structure,” she told THE WEEK. “Likewise, the windows, the Minton tiles―everything was restored to its past glory.”

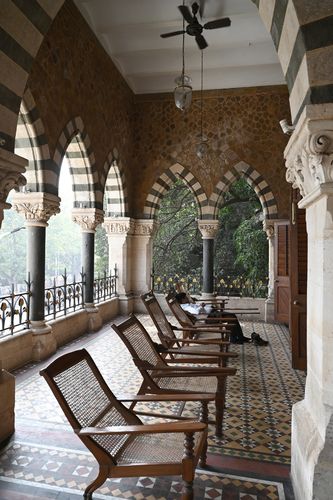

On a busy January evening, when the city is chugging along at full speed, the library offers an oasis of calm. An ornate chandelier in the centre gives the space a regal feel. After having lost close to 7,000 books, the library’s restored a rich collection of almost 28,000 books across five languages. There are banker’s lamps on the huge mahogany tables. Outside on the veranda, the planter’s chairs have been repaired, and one can comfortably settle in them and watch Mumbai in action.

Last December, Lambah received the UNESCO Asia-Pacific award for cultural heritage conservation for restoration of the David Sassoon library and the Bikaner House in Delhi. These are not the only ones though. Lambah’s firm, Abha Narain Lambah Associates, has won 13 UNESCO awards and undertaken projects as varied as the Maitreya Buddha Temple in Ladakh, the Ajanta Caves of Maharashtra, the Raj Bhavan in Kolkata, the Hampi temples of Karnataka and the Opera House in Mumbai. Her ongoing projects include restoration of Shalimar Bagh in Kashmir, redevelopment of Crawford Market in Mumbai and conservation of Victoria Hall in Chennai.

Excerpts from an interview:

Q/ Did you expect the two awards?

A/ Yes. Especially for Bikaner House, because it was the culmination of many years of work. It changed the narrative of government buildings in Delhi. This was a bus adda with paan stains and loosely hanging wires. When Vasundhara Raje was the chief minister, it was her vision to transform the place into a cultural hub and to turn it into a visiting card for Rajasthan in Delhi. That was precisely what we did in very little time. The place is now a buzzing art space, and can host cultural events from flamenco dance performances to food festivals and book releases.

Q/ What has been your driving force as a conservation architect?

A/ When I became a conservation architect, people did not know what it meant. It was a completely new field and in India we had this notion that it was an elitist occupation. This is why my career growth did not start with restoring a palace or a monument; rather, it was grass-roots and mainstream―a historical building which is a part of the public memory. Yet, what bothered me was that despite historical public landmarks becoming an inherent part of our collective memory, we were always reluctant to fund their restoration and conservation. So, that is what has driven my entire career―making people participate in conservation. My first few projects were as founding member of Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda Association, where we raised funds through public support and restored some of the most prominent landmarks, like Elphinstone College and Mumbai University.

Q/ How crucial is it to go back to traditional knowledge systems for conserving heritage?

A/ It is extremely crucial. So when we were working on the temple in Ladakh, we went to senior Ladakhi villagers on how to mix two types of clay, on where to get the ancient local grass, yagzas, and more. We used traditional techniques that have lasted for a century, rather than getting contemporary things. In Punjab, I worked on the Qila Mubarak in Patiala and the Mughal Serai in Doraha. Seventy years after independence, there had been no conservation at all in those towns. Punjab was all about new buildings and industry. There I found two craftsmen in their 80s who knew how to work with lime to train the younger guys, because they could provide us with the right knowledge on the materials used back in the day.

Q/ Do you feel we have not yet mastered contextual design in India?

A/ In India, we either completely copy the old buildings and make a fake new one, like we did with Mumbai’s Gateway of India which had a mini Gateway of India with a fake arch that was a toilet. Or we make really bad new buildings that have no idea of scale. I learnt from my first boss, Joseph Allen Stein (known for the India International Centre and Ford Foundation at Lodhi Gardens, among others), that good architecture is built with context. So even if you build at the Lodhi gardens, don’t make fake Lodhi arches. Make a completely contemporary building, but with due regard to the original structure. In India, there are very few architects who can strike a balance between the new and the old.

Q/ Which Indian city is an example of an ideal, well-planned city in India?

A/ Jaipur for me is a well-planned city, with courtyards that bring in passive cooling and thick walls. There is strong facade and signage regulations and a mixed land use. Elsewhere in India, this whole concept of the demarcation between the residential and business area is quite bizarre. For me, mixed land use is extremely crucial―where business, homes, shops and craftspeople form a micro community within each mohalla. That was how the traditional Indian set-up was. What we have lost because of European planning are buildings which lack identity. So if you see an old city like Jodhpur or Udaipur, a material palette was ingrained in their design. Which means all of Jodhpur used the same material and every [building] had the same height and fenestration, thereby giving a uniform identity to the entire town. Today, that is missing, with everyone building in their own way.

Q/ Do you think we have lost Mumbai to bad planning and greed?

A/ The Backbay Reclamation Scheme of Marine Drive reclaimed a lot of land and created a strong urban design. I worked on making Marine Drive a world heritage site. What is so special about it is that there is this strong massing, every building is of the same height and there is an overarching urban design statement. And then you look at Andheri and Lokhandwala, where there are pockets of isolated planning by individuals. So, in a way, the planners and the government just lost the plot and only cared about the development fees. There was just no planning.

Q/ You say conservation is forensic in technique. Please explain.

A/ Just like in forensics, you need proof to make decisions. Conservation is a lot like that. When we take on a project, we go into the archival history, look at the drawings, and the archival photographs. We found old photographs of side balconies at the Opera House, which at the time had been removed. Also, we found proof that the interiors were baroque and not art-deco. Because when I found it, it had an art-deco interior which had been redone at some point. So it was very important to establish at what time they changed it and what were the colour schemes used, because black-and-white photographs don’t reveal the colour. So we had to go through an old film starring Rajesh Khanna, the climax of which was shot in the Opera House, and that showed us the design of the balcony and the colour scheme then. When I was restoring the Mani Bhavan in 2004, all images were in black-and-white. So I went to a house across where an old man remembered the [erstwhile] colour scheme.