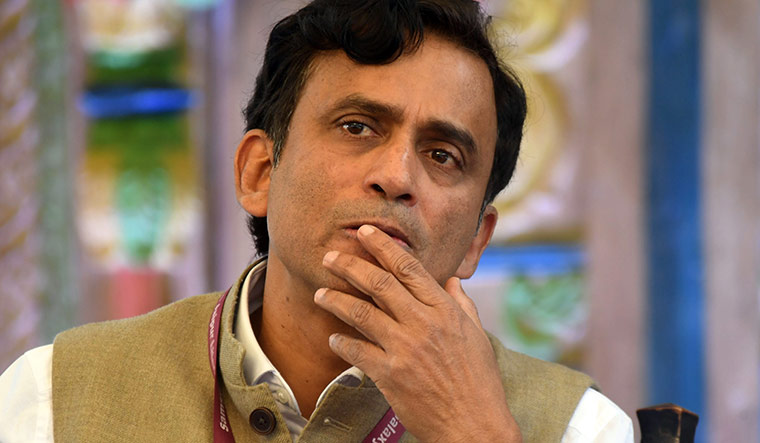

Interview/ Nikhil Alva, author

Nikhil Alva’s first novel, If I Have To Be A Soldier, is shaped by his childhood journeys to the northeast. Thriller-like, vividly told and set during the Mizo insurgency, the book preserves the painful memory of the bombing of Aizawl―a fact forgotten, but which has found a new life in fiction. Excerpts from the interview:

Q/ Why did you choose to write this book?

A/ My mother was in charge of the Congress in the northeast. She took us on road trips. In the 1970s, insurgency was at its peak in Nagaland as well as Mizoram. For a young boy, this was quite scary. We couldn’t drive at night; security forces [were] all around; and there was this fear that permeated every exchange. We would be introduced as say, ‘Oh, they’ve come all the way from India, please welcome to India.’ I didn’t understand where that was coming from. My interest in the northeast started there.

I got hooked on to the idea when I first heard of the mautam 15 or 20 years ago. (Mautam is a cyclic ecological phenomenon that creates widespread famine in the northeast every 48 years.) I was fascinated by the linkage―the causality of the bamboo flowering once every 48 years, which leads to this plague of rats, which leads to this massive famine. Because it is mishandled, thousands die and that leads to this brutal 20-year insurgency, where thousands more lose their lives. It is a very powerful story with layers.

Q/ The leap into fiction is not always easy. Why fiction, rather than nonfiction?

A/ I chose the medium of the novel because I felt that nothing else will do justice. The insurgency is quite old now. Very few insurgents are alive, [and] they are quite old. I didn’t have the experience, the expertise or the volume of research that will be required for a nonfiction book. I felt that a novel with fictional characters, but against the backdrop of historic events, was perhaps the best way for me to get into this story.

Q/ You write about Aizawl being bombed. It is a memory that has been wiped out. Could you really talk about that memory?

A/ The tragedy is that there is so little information available of what actually happened. Sometimes we like to forget uncomfortable events or truths in modern history. Among all the uncomfortable events, the bombing of Aizawl stands out. It is the only time in our history where we used our Air Force to bomb our own people. [Many] innocent civilians lost their lives. We have no count of how many people died. It is all anecdotal evidence. We denied this bombing completely for the longest time.

But it is not just the bombing. The other terrible thing that happened was this concept of progressive villages―where over 80 per cent of the Mizo population were, at the barrel of the gun, relocated. These villages [were] nothing but internment camps, along the highways and behind barbed-wire fences. Traditional villages were just burned to the ground. We don’t talk about it. We don’t write about it. It doesn’t feature anywhere. It’s like, it didn’t happen.

That is dangerous because history is not always glorious and wonderful. There are things that have happened that, as a people, we should not forget. If you forget, you tend to repeat the same mistakes again.

Q/ Do you see a parallel with what happened then and what is happening in the northeast now? This idea that there is this conflict still burning at the edge of India, and we don’t understand it.

A/ The most important commonality between these different incidents is a lack of dialogue. The Mizo insurgency could have been averted well before 1966. There was resentment. There was anger. They felt they were being taken for granted. Their voice was not being listened to. No one really paid attention. The insurgency finally got resolved with the Indian government conceding that there was a lack of dialogue.

These problems have been simmering for a long time in Manipur. There has been very little dialogue, little attempt to get both sides to the table to sit down and resolve differences peacefully. It will take years now to heal the wounds of [what happened] last year. We will need to give people an opportunity to be heard, to listen to those voices. Not from a perspective of tokenism, but actually listen, which means engaging in a meaningful dialogue.

Q/ You talk about meeting insurgents as a child and being struck by their sadness and sense of loss.

A/ As a child, I didn’t really understand these concepts. I knew that there was trouble. I knew that there had been violence. I had listened to conversations because of my mother’s work, I [used] to meet some former insurgents who had come out of the so-called underground and into the political mainstream.

They had stories to tell. Some of them would be lighthearted and funny, but with this underlying sadness for the number of years lost to violence. I picked up emotions―sadness, the feeling of betrayal―without fully understanding the intellectual and ideological side of what actually happened.

The intention is not to make [the novel] political, but to say that violence impacts regular people who are trying to lead perfectly normal lives. They get caught up in a swirl of events, and their lives get shaped by them.