It is a sultry evening in Delhi and we are at the Alliance Francaise de Delhi for the launch of French-American economist and Nobel winner Esther Duflo and illustrator Cheyenne Olivier’s latest book, Poor Economics for Kids, consisting of stories that aim to sensitise children to the world around them. Duflo, dressed simply in a red kurta, has an effervescence about her as she endeavours to answer the questions of her young audience. Like that of a boy of around 12, who refers to her Nobel speech about wanting to make people understand poverty. “By writing this book, have you achieved it?” he asks. Duflo is patient yet encouraging, smilingly explaining that the job of eradicating poverty can never be fully over, and so she will continue to write more books and work towards it.

But the question that really intrigues her is one by a librarian in the back. If one has not experienced poverty, how can they connect with the story? It is a good question, one which harks back to Duflo’s own childhood. She never knew poverty, for she comes from a privileged background. Her parents―a paediatrician and a maths professor―raised her in a western suburb of Paris. All her knowledge of the underprivileged came from her mother, who volunteered across the world and worked closely with children who were victims of war. “I was amazed and somewhat awed by my luck: how come I, Esther, get to be born in this middle-class, intellectual family, with loving parents, decent schools, and all the food and books I need, while some other kids are born in Congo, in the middle of a war, and are forced to carry a Kalashnikov to fight?” she asks in an essay written when she won the Nobel Prize for Economics, along with her husband, Abhijit Banerjee, and colleague Michael Kremer, in 2019.

She attributes her confidence to a quirk of nature―being tiny as a child. She only learnt to read at six, but since she looked like a four-year-old, adults thought she was really smart, which then worked like a self-fulfilling prophecy. In fact, even becoming an economist can be put down to fate or fortune, rather than any well thought-out plan. When she got admission to the Ecole Normale Superieure, an elite higher education institution in France, she was unsure about what subjects to take, being a “jack of all trades”. She chanced to encounter the professor of economics, who was then recruiting students for his department. He convinced her to give economics a go. Later, she almost did not make it to MIT, because an admissions officer initially put her file in the reject pile. As luck would have it, she came to work under that officer when she got admission, and many years later, he would become her life partner. They would go on to win the Nobel for their “experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”.

In fact, her current book, too, draws from one that she co-wrote with Banerjee in 2011: Poor Economics: Rethinking Poverty and the Ways to End It. “Kids are the best readers,” she says. “As a child, I wanted to write for children. I have many unfinished stories from back then. But growing up, I realised it is not easy to write for them.” Duflo―who is currently the Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics at MIT’s Department of Economics―visited India, Africa, Indonesia and Latin America to research the book and develop the 60 odd characters in it.

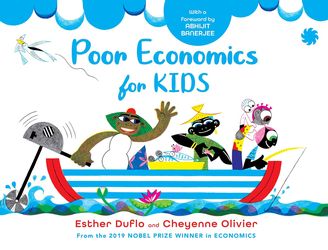

The book, which has been beautifully illustrated by Olivier, tells the story of Nilou, a young dreamer, and her friends Afia, Imai, Najy, Neso and others. Rather than directly tackling the issue of poverty, Poor Economics for Kids approaches it from the periphery, dealing with a host of issues like climate change and health care. In one story, for example, Afia is sick, but her pharmacist father is helpless. Having previously purchased cheap drugs to save money, he mixes and administers them to his daughter. If only Afia had been vaccinated and, as a rule, doctors treated the disease instead of pandering to the demands of the patients and their families, all would be well. In many cases, the poor suffer because they are unaware of the government’s provisions and policies.

As Banerjee says in the foreword, “Sometimes, it is also because no one bothered to explain to the poor how the system functions, what their rights are, who to go for questions, whom to complain to if need be. Understanding this is very important, because too much of the discussion in the world about the poor is wrong-headed. It ignores just how hard it is to be poor and therefore blames them for the problems of their own lives.”

Chiki Sarkar, founder of Juggernaut Books which published Poor Economics for Kids, says that the best part of publishing Duflo’s work is that she approaches the subject from a human perspective, and not as the “exotic other”. “She tries to get in the head of people, looking at their behaviour, and why they do what they do,” says Sarkar. “Empathy is at the heart of Esther and Abhijit’s work always.” In fact, this concern for others is the one thing that has always driven Duflo, right from helping her classmates with homework in school to helping out in soup kitchens to volunteering in a prison for a year in college.

The names of the characters and the places in the book are deliberately kept vague so that the stories are universal and can be read by anyone of any age. “Chiki asked me to have some Indian names for the characters,” says Duflo with a smile. “I said ‘not at all’. It was not our job to make characters look like real-life persons, but to discuss the economic ideas behind poverty. I wanted to bring the understanding that the lives of kids living in poverty can be similar in some ways and different in other. I wanted to set the story in an imaginary place.”

However, Duflo did ensure to get feedback from a very important person in her life―her 11-year-old daughter Noemie. “She would share her comments with us when we were all stuck inside the house [during the Covid lockdown],” says Duflo. So, how do two Nobel laureates in economics divide up unpaid labour at home? posed The New York Times during a 2021 interview. Household chores are divided equally, with Banerjee taking care of all things culinary, including menu-planning, shopping and cooking, while she does all the logistics: paying the bill, fixing stuff and paying taxes. If one glimpses a reversal of gender norms here, it is probably incidental. For a girl who wanted to be a boy when she was young, Duflo has certainly proved that girls can do everything boys can.

Poor Economics for Kids

By Esther Duflo and Cheyenne Olivier

Published by Juggernaut Books

Price Rs999; pages 345