Ajournalist once asked Ang Tsering how much he had earned per day on the 1924 Everest expedition, his first. The Sherpa replied, “Twelve annas, that’s three-quarters of a rupee.” At the time, a rupee could buy 15 kilos of rice. Tsering would otherwise make ten rupees a week as a woodcutter. Asked why he went to Everest for less money, he replied, with a grin, that the work as a Sherpa was easier.

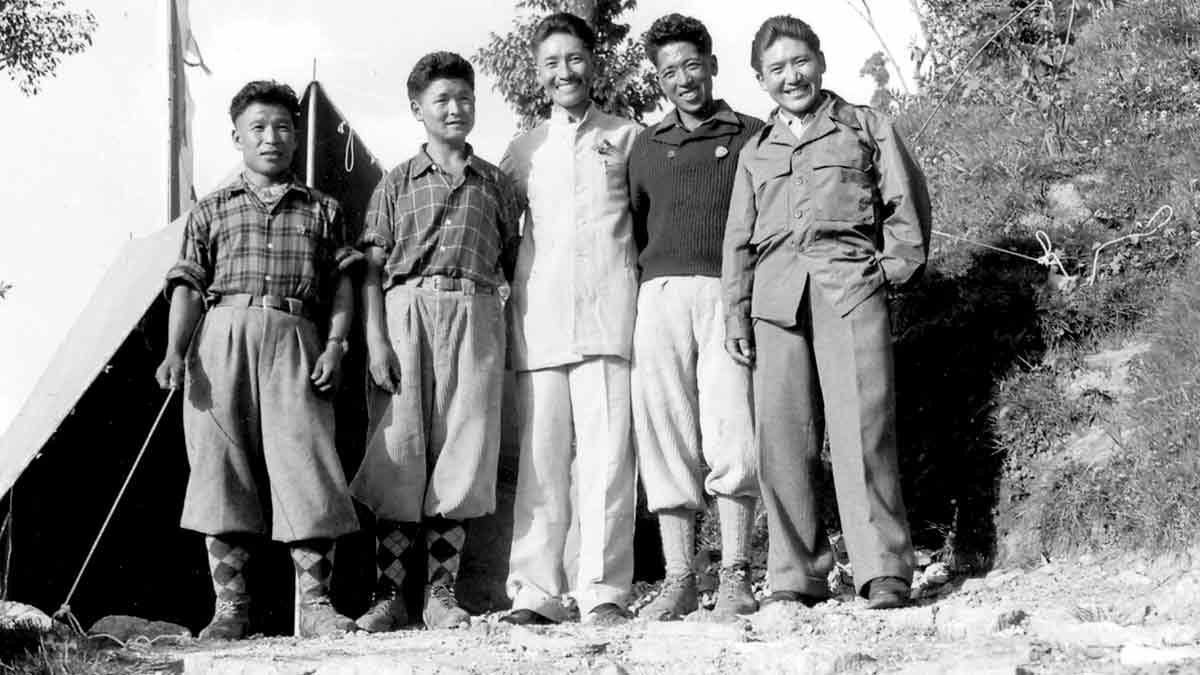

In their latest book The Sherpa Trail―Stories from Darjeeling and Beyond, authors Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar describe Tsering in a way that could be representative of the Sherpa community of the past: “Always smiling in photos, his crinkly eyes and creased brown-paper skin indicating a life in the sun, hearty kindness scribbled everywhere.”

The authors, the former a writer and editor of the Himalayan Journal and the latter a writer and illustrator of children’s books, recount gripping tales about the life and times of porters. The community that is often relegated to the background as a supporting act finds itself front and centre in the book. It is a compilation of many untold stories, narrated by eminent Sherpa Dorjee Lhatoo and other Darjeeling-based members of the community.

The book is divided into three parts―while the first is dedicated to the understanding of the history of mountain porters, the second focuses on Sherpas and their stories. There is a chapter titled ‘Bedrock’, about Tenzing Norgay, who made front-page headlines in 1953 as the first man, alongside Edmund Hillary, to ascend Mount Everest. A year later, then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurated the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling, hoping the school would produce “a thousand Tenzings”.

Part three talks about ‘The Great Indian Dream’, ‘The Lost Legacy’, and how ‘In every home is an Everester’. This is a book about young Sherpas and expedition workers, their stories of triumphs and failures. There are nail-biting moments in some of the most inhospitable conditions as they climb in thin air with loads “as heavy as human bodies”.

“The seeds of this project were planted in early 2012 in a remote area of Arunachal Pradesh in the eastern Himalaya,” note the authors. “We were hiking with our old friend and trekking companion Harish Kapadia when he told us a fascinating story about the legendary climber Pasang Dawa Lama of Darjeeling―jumping naked into the icy waters of a Nepali river to advertise his having slept with one hundred women―that ignited our imagination about the community of Sherpa climbers in that hill town. We wanted to know more and that’s how it all began.”

Expeditions, write the authors, meant work and money for the Sherpas. A good performance on the mountain would be noticed and ensure employment next time; upon returning, one could also sell equipment.

But there was also fear. For four or five months, it would be left to the women to keep the family going until the men returned. And then there was always the looming fear of the men not returning; and if they did, would they be frostbitten? Would they have lost a finger or a toe, making them incapable for the next assignment?

What makes the book especially interesting is the first-person narration by the authors who actually met the Sherpas. They provide a detailed account of their experience with the Sherpas, their families, the way the homes are structured and decorated, and the way the medals are preserved and memories cherished. There is rarefied air in the pages, and more than a peek into a lot of peaks.

Edmund Hillary loved us...

Excerpt:

Once, said Ani Daku, a sick tourist left at basecamp wanted an omelette, but Daku did not speak English. The tourist made signs to start the stove, then said, “Cock-a-doodle-doo.” Ani Daku finally understood, and made the omelette. “He gave me a beautiful new sweater. And he also gave me five rupees!” she recalled. Ani Daku’s job was also to make the porters’ tea: “I would wear gloves and a feather coat and break ice with an axe. Then I put the ice in big buckets, put wood together, and lit it with kerosene to heat the ice and make water. That was my work,” she told us.

Ani Daku married in 1955 at age thirty. Marriage brought with it dreary everyday struggle. Her husband ran a business selling butter, the yak cheese churpi, ghee, and eggs in Darjeeling. They then moved to Sikkim, where for fifteen years they supplied ghee to the king’s household. When her husband died, Daku took over running the shop along with raising their children. Daku never went back to carrying loads, but she missed that life. “It was so much fun to roam around!” she told us. “What’s there in staying at one place? You feel better when you travel, don’t you? You don’t feel bad about carrying loads, if you get to travel!” Daku remembered returning to Kathmandu with a triumphant team after the conquest of Everest in 1953: “When we arrived at Nepal, there were many people and flowers to celebrate. We rode an elephant. We queued to meet the king. I was given documents after this and a notebook by The Himalayan Club. But it was left at Tenzing Sherpa’s house.”

Hillary gave her a badge and a watch too, but that was more than six decades ago and she has no recollection of where they ended up. Ani Daku recalled, “Hillary was very tall, very fair, and had a long face. Very handsome. And he used to put his arm around my shoulder when I was tired. He loved us.”

As evening approached, Daku’s daughter told us, “Our mother regrets that she’s not educated. She told us not to be like her and worked hard to educate all five of us.” We asked whether Ani Daku had a message for the younger Sherpas of Darjeeling. “I pray that they get the best. That people may have no suffering!” she said. We left with the realization that Ani Daku, despite not having gone to school, was far more learned than most.

THE SHERPA TRAIL: STORIES FROM DARJEELING AND BEYOND

By Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar

Published by Roli Books

Pages: 352; Price: Rs695