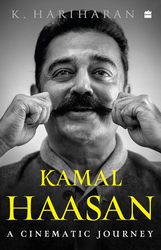

At the Town Hall hosted by THE WEEK in 2017, actor Kamal Haasan was suave and articulate, as though stardom was second nature to him. The consummate performer in him dazzled, whether through his vast knowledge on everything from cinema to classical music (“I grew up listening to Muthusami Dikshithar’s [Vatapi Ganapatim] hymn as my mother loved Carnatic music”) or through the wit he deployed while fielding certain questions. As a journalist, I had for the last 25 years followed his career in cinema and politics, and his arduous efforts to nail roles which a lesser actor could not have pulled off. Yet, I had not had my fill of Haasan; the more you tried to untangle the enigma that was him, the more tangled you got. That is why I was eager to read a new book on him―Kamal Haasan: A Cinematic Journey―by K. Hariharan.

The book is written in a self-assured style, opening in the town in south Tamil Nadu where Haasan was born. Though Hariharan largely sticks to Haasan’s cinema career, the first chapter begins with his early influences, the dynamics of his liberal family and his mother’s impact on his life. Though not formally trained, Haasan learnt from observing his family, friends and the filmmakers that he admired. He was intent on mastering whatever he put his mind to. His sister Nalini, for example, describes in the book how Haasan was envious of her for listening to Elvis Presley and Nancy Sinatra. He was only 12 then, but was determined to improve his English. Years later, in his film Nala Dhamayanthi (2003), he sang an Indian classical song with Presley-style rock and roll. More than consummate, Hariharan describes him as complete, with an enviable arsenal of skills.

The writer chooses 40 of Haasan’s 260 films, dwelling on their political context and global influences. For example, in Varumaiyin Niram Sivappu (1980), set in the backdrop of Emergency, Hariharan explains why director K. Balachander chose Haasan to play the poet Rangan. The duo made many movies together that encompassed social and feminist themes and progressive thinking, conveyed through a powerful screenplay. “If K. Balachander was his intellectual pillar, director SP Muthuraman was his mass appeal spring board,” writes Hariharan about the director who made Haasan a people’s hero in the 1980s. In another chapter, the author describes Haasan’s views on the “linguistic bigotry committed by some vested interests” during the anti-Hindi agitations in the state, when he was trying to transition from the Tamil film industry to Bollywood. His debut Hindi film, Ek Duuje Ke Liye (1981), in fact, looks at the grim north-south divide that existed after Emergency.

There are many anecdotes in the book about the actor who combines the rare qualities of intellectual prowess and popular appeal. There is also a deep soul-searching as the writer tries to arrive at the heart of Haasan’s allure. Perhaps it is the very nature of the chameleon in Haasan to elude definition. Whether as actor, writer, filmmaker or politician, Haasan can metamorphose as well in life as he does for his roles. Kamal Haasan: A Cinematic Journey may not have any earth-shattering revelations; still it succeeds, if not in unmasking the actor, then in describing his many faces.

Kamal Haasan: A Cinematic Journey

By K. Hariharan

Published by HarperCollins

Price Rs699; pages 260