There are more opinions on earth than salt in the sea. And when schools of fish run parallel to schools of thought, you see a scene of chaos and calm. That was Kerala’s Kozhikode beach from November 1 to 3, at the Malayala Manorama Hortus arts and literature festival.

As sweaty wisdom gatherers rushed from one venue to another, getting their fill of informed opinions, intellectual sparring and insightful commentary, the Arabian Sea stood there, vast and mostly gentle, reminding everyone that in its depths lie bundles of knowledge man is yet to unpack.

The festival saw 500 speakers across 150 sessions in six venues over the weekend. Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan inaugurated the event in the presence of Malayala Manorama Executive Editor and Director Jayant Mammen Mathew, and spoke about how Hortus was a reminder of Malayala Manorama’s historical links to Kerala’s reformation. He said that India needs a united fight for creative freedom, as many of its citizens cannot express their feelings openly.

This, of course, was not too much of a problem at an arts festival, as opinions from all sides flowed freely. In one of the sessions, former BJP general secretary Ram Madhav called for a return to Indian family values. In conversation with THE WEEK’s Resident Editor R. Prasannan, the senior RSS leader spoke about Hinduism being a cultural identity and not a political one.

Shashi Tharoor, a senior Congress MP and a veteran on the literature circuit, said that for a nation to be united, the interests of all communities must be taken into account. He also spoke about caste in India and shared an anecdote about his classmate and later Bollywood hero Rishi Kapoor asking him if he was “a Brahmin or something”.

Tharoor also denied thinking about joining the BJP and touched upon Hindi imposition, a topic taken up more strongly by Tamil Nadu Deputy Chief Minister Udhayanidhi Stalin. In one of the more popular sessions of Hortus, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam leader spoke about literary echoes in Dravidian politics as light rain fell on applauding listeners.

Tamil Nadu Deputy Chief Minister Udhayanidhi Stalin speaks at the festival | Ujwal P.P.

Tamil Nadu Deputy Chief Minister Udhayanidhi Stalin speaks at the festival | Ujwal P.P.

“I stand before you with a sense of pride that the struggles carried out by the Dravidian movement in Tamil Nadu have saved most of the Indian states from falling prey to Hindi imposition,” he said.

Politicians, of course, drew more eyeballs but the festival featured personalities from across artistic fields, including writers such as Perumal Murugan and Anand Neelakantan, Polish essayist Marek Bienczyk, film stalwart Adoor Gopalakrishnan, noted musician Hariharan and mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik.

There were impromptu appearances, too, like when senior Congress leader Mani Shankar Aiyar sat in the audience for a session with former president Pranab Mukherjee’s daughter Sharmistha, and even asked a question when the floor was thrown open to the audience. He then sauntered off to his own session.

Actors Kani Kusruti and Divya Prabha, director Payal Kapadia, film editor Beena Paul and festival director N.S. Madhavan | Russell Shahul

Actors Kani Kusruti and Divya Prabha, director Payal Kapadia, film editor Beena Paul and festival director N.S. Madhavan | Russell Shahul

Kozhikode beach is a sea of humanity on most weekends; an arts festival of this scale only increases the shoulder-to-shoulder contact. Especially popular offerings like the Kochi Biennale Pavilion, South Korean chef Hyeonju Park’s kimchi-making workshop, stand-up comedy by the likes of Abish Mathew and the well-stocked book stall. Also in demand were bottles of water, ice cream and fizzy drinks. The heat did its own speaking. One stall owner, though, missed out on part of the payday—he had lemon sodas and brined fruit, but had not yet subscribed to the revolutionary technology of UPI.

The crowd spilled out to the beach road, too, where the evenings saw bumper to bumper traffic and blaring horns competing with the live music on the beach. An autorickshaw driver told me that such snarls were rare, while another asked expectantly whether Hortus would return next year.

The Kochi Biennale Pavilion | Russell Shahul

The Kochi Biennale Pavilion | Russell Shahul

Away from that frenetic pace, we headed to another Hortus event about 20km from the main venue. This was at Tulah, a sprawling wellness retreat that seemed a world away from the beach. Hortus, by the way, comes from Hortus Malabaricus (Malabar Garden), a 17th-century Latin botanical treatise that documented the varieties and medicinal properties of the flora of the Malabar coast. Tulah had many of the plants mentioned in the historical text. The guests, many of them speakers at Hortus, were taken for a tour of the garden.

The sessions at Tulah focused on wellness, and included speakers such as Olympic bronze-medallist Leander Paes, retired naval officer and ocean sailor Abhilash Tomy, fitness instructor Deanne Panday and actor Roshan Mathew.

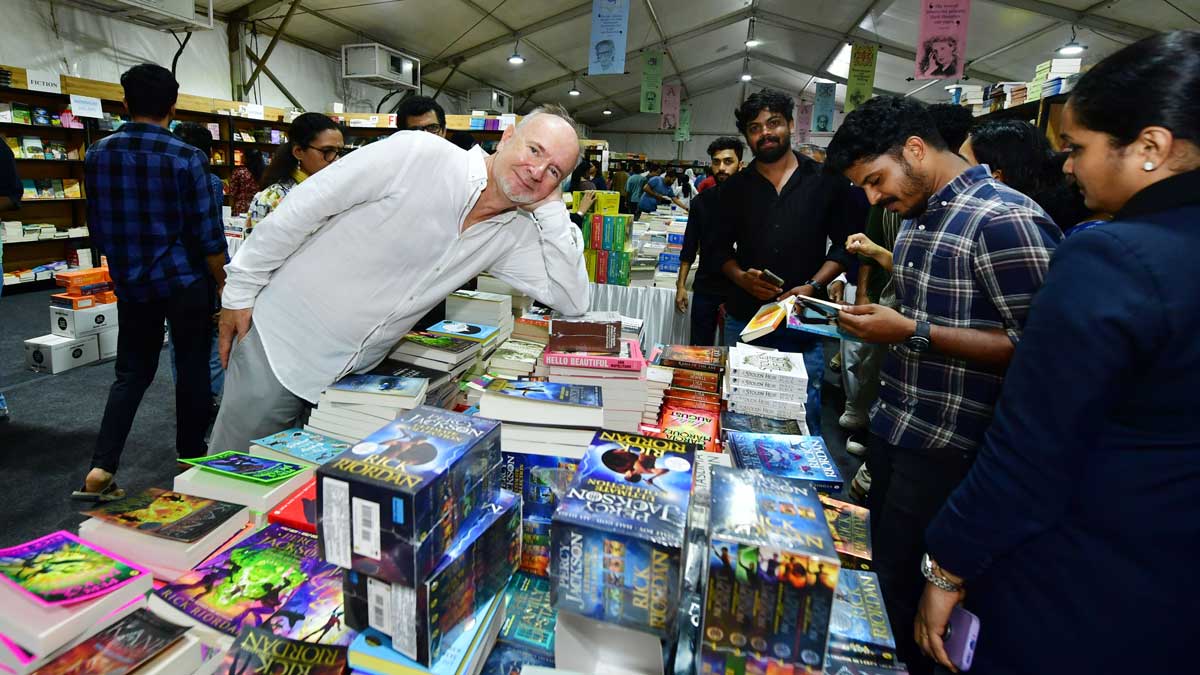

Polish author Marek Bienzyk at the book fair | Russell Shahul

Polish author Marek Bienzyk at the book fair | Russell Shahul

In the outdoor venue, under a setting sun, Paes recounted his wellness journey. In 2003, he was diagnosed with a cancerous tumour, which later turned out to be a mistake; it was actually parasites in his brain. “The entire first round of chemotherapy was useless and I had to go through another six weeks of steroidal treatment. I put on 128 pounds. I had no hair on my head, no eyebrows or eye-lashes. My parents wanted to remove the mirrors from the house, but I said no…. That is where I turned a corner on wellness…. In six months, I lost the 128 pounds naturally.”

It was an inspiring session, reminding us that for ideas to germinate and explode, an active mind is priority number one. And that is where wellness and all allied aspects come in. Faizal Kottikollon, founder and chairman of KEF Holdings, who owns Tulah, said he set up the retreat in keeping with his ethos of “positive disruption”.

Perhaps festivals such as Hortus can do the same; infuse life into public discourse and encourage healthy discussions beyond the boundaries made by man. After all, staring at the Arabian Sea, the rigid structures we create do look a bit silly.