A few weeks after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, president Shankar Dayal Sharma made a presidential reference to the Supreme Court under Article 143(1) of the Constitution seeking its opinion on whether a Hindu structure existed at the site of the mosque before it was built.

A five-judge bench headed by chief justice M.N. Venkatachaliah dismissed the petition by a majority of 3:2, terming it as “superfluous and unnecessary”. However, justices A.M. Ahmadi and S.P. Bharucha put forth a minority opinion in which, even as they declined to answer the reference saying the court had no possible way of knowing whether a temple existed on the site before the mosque was built, they pointed out that it was clear that the government did not intend to bind itself by the judicial decision.

It amounted to a castigation of the Narasimha Rao government’s perceived inaction that led to the demolition of the mosque. It also highlighted that the presidential action sought to “favour one religious community and disfavour another”.

A biography of justice Ahmadi written by his granddaughter Insiyah Vahanvaty brings out the behind-the-scenes tension in the court as it dealt with the matter. She writes that Ahmadi was under intense pressure to agree with the majority. Ahmadi has described in his personal writings, as reproduced by Vahanvaty in the book, The Fearless Judge: The Life and Times of Justice A.M. Ahmadi, the discussions of the bench. As he walked into a meeting of the judges, he noticed that while justices Venkatachaliah, G.N. Ray and J.S. Verma were present, Bharucha was not. Ahmadi said it was improper to conduct the discussions in Bharucha’s absence. To this, he was told, “Once we four agree, he, too, will agree.”

Ahmadi looked at the draft judgment and found that by upholding the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act, the bench would be tacitly sanctifying the acts of trespass and destruction. He told the chief justice that he would sign the draft if they amended it to include the allocation of a small piece large enough for a Muslim cleric to spread a mat and offer namaaz, especially since the Act effectively included retaining the idols placed there and requiring pujas to continue. Venkatachaliah and the two other judges refused outright. The next day, Ahmadi spoke with Bharucha, and they agreed to record their dissent. It was a time when Ahmadi was poised to take over as the next CJI, and he knew that the minority opinion could jeopardise it. But he opted to stay true to his ideals.

His children and grandchildren recall the extent of pressure Ahmadi faced. Vahanvaty writes about one such instance. Ahmadi had received a phone call one evening when the family was having dinner. He went to the bedroom to take the call, a clear indication that it had to be confidential. The rest of the family continued with their meal and were jolted into a pause when they heard the booming voice of Ahmadi as it travelled down the corridor: “I don’t care about becoming chief justice, I won’t do it!” He did not return to the dining table. He never revealed who was at the other end of that call.

The book brings out the personal side of Ahmadi and throws light on the stuff that he was made of as he dealt with one of the most significant moments in India’s social and political history.

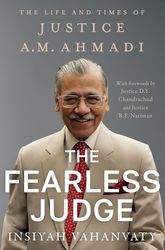

The Fearless Judge: The Life and Times of Justice A.M. Ahmadi

By Insiyah Vahanvaty

Published by Juggernaut

Price Rs899; pages 325