In the late eighth century AD, a delegation from the Raja of Sindh arrived in Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, the newly-founded Islamic empire. The delegation came with gifts to appease Caliph Abu Ja’far al-Mansur. What caught the Caliph’s eye was not the jewels, mangoes or the expensive cotton weaves, but a single manuscript. The book, which the Arabs came to call The Great Sindhind, contained complex mathematical theories and scientific ideas, compiled by ancient India’s greatest scientific mind, Brahmagupta.

This uncharted westward journey of Indian mathematics is retraced by historian William Dalrymple in his latest work The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World. With arresting details, the writer takes us back to ancient India and the Abbasid Caliphate, where the ancient manuscript was eagerly welcomed.

The Great Sindhind included not only the idea of zero but also those of crucial mathematical concepts like trigonometry and algebra. It ended up in the hands of the viziers of Baghdad, from where these ideas spread across the Islamic world. Five hundred years later, they reached Leonardo of Pisa (Fibonacci), who popularised them as ‘Arabic numerals’ across Europe.

Only these numerals weren’t really Arabic, but Indian.

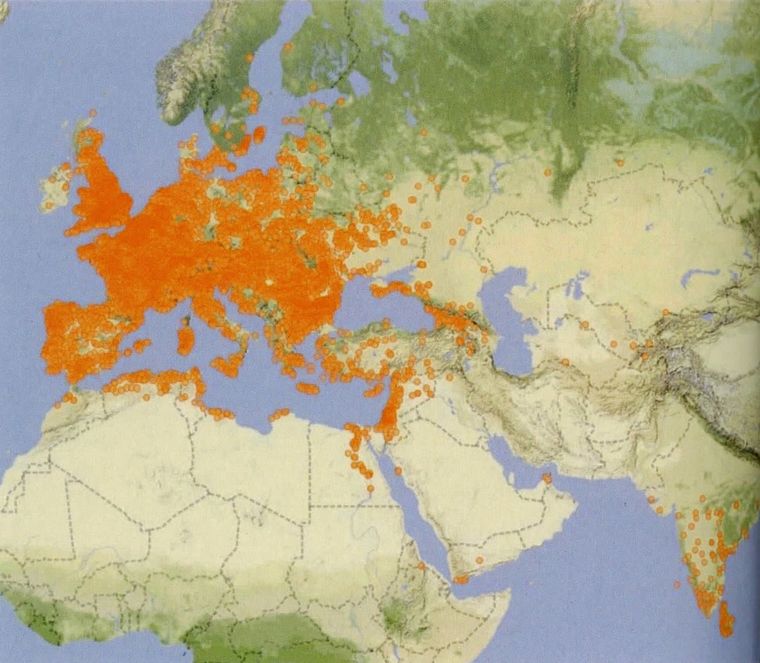

Ancient India’s contribution to reshaping the world was not just limited to mathematics. From here came merchants, missionaries, monks and artists who took their ideas across south, central, southeast and eastern Asia. Together they paved a ‘Golden Road’ that stretched from the Red Sea to the Pacific.

So it is only natural that an Indophile like Dalrymple felt that this extraordinary but little-known tale of ancient India needed a retelling.

Basking in the cool breeze from the backwaters of Kochi, Dalrymple excitedly recounted to THE WEEK how this book was a debt he owed to his younger self. As a Scottish boy interested in the ancient world, Dalrymple’s first foray outside Scotland was to London to see an exhibition on Tutankhamun, the Egyptian pharaoh, at the British Museum. “My younger self would be surprised that I spent much of my life writing about the uninteresting 18th century and the East India Company rather than the ancient world,” he says.

Dalrymple has made amends with this book. The first spark for The Golden Road came during one of his visits to the Ajanta Caves, where some of the earliest Buddhist paintings were being restored. “I saw that there had been a massive restoration of the earlier frescos in caves 9 and 10. But no one had written about it despite it being the oldest Buddhist painting in the world. I took six months off and began writing about these early murals. That also got me back into writing about India’s ancient history and early past,” he says. He then set out on a journey which first took him around the ancient sites of India, and then to Cambodia, Laos, Java and Sri Lanka, where Indian influence was most dramatically transformative.

The extensive research revealed a picture of India’s deep trade links with the Roman Empire. He notes how Indian goods were transported from Kerala’s Muziris in fleets of over 250 boats to the ancient Roman Red Sea port of Berenike. Propelled by the cold dry winter winds from the Himalayas, these vessels were filled to the brim with black pepper, linen and even elephants for the Colosseum. They returned six months later with Roman riches riding the monsoon winds. Such was the extent of trade that Roman naval commander Pliny the Elder remarked with disdain, “There is no year which does not drain our empire of at least 55 million sesterces.”

Dalrymple’s interactions with archaeologists P.J. Cherian and Steven E. Sidebotham, who excavated Muziris and Berenike, respectively, enriched his knowledge of the trade links. “One thing that powered the new understanding was the discovery of a manuscript called the Muziris Papyrus, a shipping invoice found in Egypt. It talked about one container with 200 tonnes of ivory, huge quantities of black pepper, nard (a valuable Himalayan product used in perfumery), cotton and silk,” he says. “If the importer succeeded in getting it to Alexandria, this container alone would have made him the ‘Elon Musk of Roman Egypt’.”

Despite its enormity, this vast trade link has somehow paled in comparison with China’s Silk Road. Dalrymple fiercely argues that the Silk Road did not exist in the ancient world. “Everyone has come to assume that it was a real thing that existed in antiquity,” he says. “It was not and the term was invented only in 1877 by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen. It first entered English in 1936, in a travel book by the Swedish Nazi Sven Hedin, and only gained popularity after the 1980s.”

However, India’s biggest export was not its produce, but its religions―Buddhism and Hinduism. The monks who traversed the Asian continent through China, Japan, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Siberia took with them not just the language of Sanskrit but also the whole of Indian literature.

To narrate this story, Dalrymple paints in vivid hues the two main characters―a monk and an empress. While Xuanzang is known in our history lessons as the monk who took Buddhism east, Empress Wu Zetian impresses Dalrymple with her machinations and calculations. “Empress Wu is probably my favourite in the book,” Dalrymple says, describing how she made the Buddhist monks from Nalanda hail her as the “great goddess” and the reincarnation of Maitreya (the Buddha of the future, born to teach enlightenment in the next age). “Her time is the maximum moment for Indian Buddhists in China,” he adds.

But why weren’t India’s contributions hailed? Dalrymple attributes it to the aftermath of colonialism. “While the early British like Sir William Jones and my ancestor Sir James Prinsep were very enamoured with Indian culture, [those who came later] like Macaulay were dismissive,” he says. “Macaulay famously wrote that a single shelf of good English books is worth more than the whole native library of India and Arabia. The British could hardly claim to be bringing civilisation to a country that had already been exporting it for 3,000 years. There was also an undermining of Indian ideas and no attempt to teach about Indian mathematicians like Brahmagupta, the way they taught us about Pythagoras and Archimedes.”

The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World

By William Dalrymple

Published by Bloomsbury

Price Rs999; pages 496