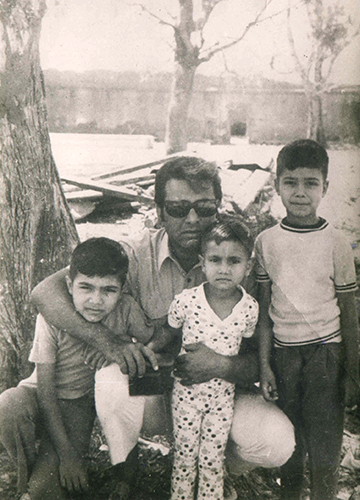

Mohammad Ali Baig had an idyllic childhood in a stud farm with ponies as playmates. Afternoons would be spent riding horses or playing cards and caroms with his father, the legendary thespian Qadir Ali Baig. In the evenings, the house would bustle with his father’s theatre buddies. Qadir was a big foodie, and insisted the visitors be served authentic Hyderabadi cuisine. He also insisted on strict decorum in the house. After school, for example, his children were not allowed to rush to the dining room; they had to be properly attired for meals.

Still, Mohammad always looked up to his father. Qadir knew how to balance personal and professional life, ensuring he spent quality time with his family. However, his joy was short-lived when his father grew ill in his adolescence. Qadir always loved to celebrate special occasions. In his final days, however, he could not leave the house to buy gifts. Mohammad remembers his father’s last birthday gift to him, a few months before Qadir died at the young age of 46.

“Early in the morning, my father walked into my bedroom and gifted me the pen he used to write with,” says Mohammad. “That was his last gift to me. I wanted to think that this was the pen that would give me the might to write such legendary plays as my father. But I never had the courage to use it.”

He might never have used the pen, but he did end up writing plays as compelling as his father’s, though his journey in theatre took a more circuitous route. As a child, he was convinced he would never follow in his father’s footsteps. Watching Qadir and his team rehearse a production, he found theatre to be very intense. Then there was the heartache―months of rehearsals, costume designing, stitching, set building, footwear making would all go in a few shows. To young Mohammad, it seemed a waste of time and effort. So, after his studies, he went into ad filmmaking, directing over 450 ad films and social documentaries in seven countries in less than a decade. It did not satisfy him, though.

“At the end of the day, you’re just selling soap and shampoo,” he says. “There was no fulfilment.”

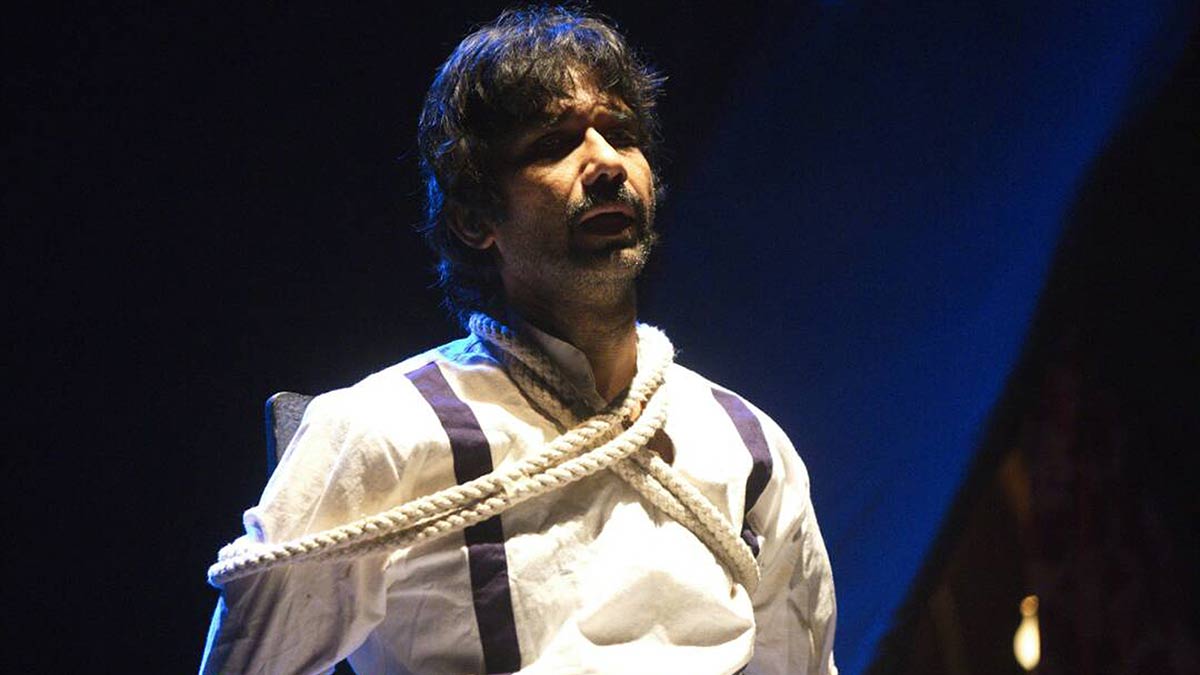

Stage might: Mohammad in his play Quli―Dilon ka Shahzaada.

Stage might: Mohammad in his play Quli―Dilon ka Shahzaada.

It was on his father’s 20th death anniversary, when he heard some of the most renowned theatre personalities in India talk about Qadir with respect and fondness, that it struck him just how great his father’s legacy was. He knew then that he had a responsibility to safeguard and take it forward. That was his initiation into the world of theatre. He started the Qadir Ali Baig Theatre Foundation and the Qadir Ali Baig Theatre Festival in Hyderabad in 2005―one of the most prestigious theatre festivals in the country.

He, of course, has big shoes to fill. Born at the Ahmed Bagh Palace, Qadir had a fairytale upbringing. Taking after his father, the international polo player Mirza Mahmood Ali Baig, Qadir loved horse racing and breeding. But his first love was theatre, born during his days at the Aligarh Muslim University. In 46 years, Qadir produced 46 plays. In fact, the 1970s and early 1980s are considered the golden era of Urdu and Hindustani theatre in Hyderabad, thanks largely to Qadir’s riveting historical spectacles and social satires.

“He was so popular that tickets of his plays would be sold in the black market. A ticket that cost Rs5 would be sold for Rs50,” says Mohammad. “The transport department even arranged for buses to take people to the Golconda Fort when my father’s play Quli Qutub Shah was being staged there. It is even more incredible when you think that my father achieved this [level of popularity] without an innings in Bollywood or television.”

This skill of blending commerce and art is something that Mohammad has learnt from his father. Those days, either you made art-house productions or those that sold well. The two never merged until Qadir came along. And today, his son has taken forward that legacy. In a way, he has become the global face of Indian theatre, receiving honours from the French and Canadian governments and staging his plays at Oxford University and the prestigious Edinburgh Festival Fringe. He was awarded the Padma Shri in 2014, becoming its youngest recipient in theatre.

For long, it has been his mission to revive theatre in Hyderabad. It has not been easy. The world has greatly changed since his father’s time. Today, theatre is facing competition from OTT and YouTube. With attention spans getting shorter, it is a task to get people to watch your play when they have the more convenient option of watching Netflix from the comfort of home. Theatre also lacks a proper ecosystem in the country, feels Mohammad. “Beyond the audience and the performers, you need a support system,” he says. “You need venues, funding and sponsorship. People don’t put into theatre the same commitment and conviction that they put into other professions. For most, it is still a hobby. You can’t say it is because theatre does not pay well or is not professional in India. We theatre artistes must make it professional.”

Still, theatre, when it is done well, will always have takers, he feels. Whether it is the love story of Quli Qutb Shah and Bhagmati in his play Quli: Dilon ka Shahzaada, or that of Taramati and Sultan Abdullah Qutub Shah in Taramati―the Legend of an Artist, people have come in droves to watch. He recounts the time in 2014 when he went to perform Quli: Dilon ka Shahzaada at a theatre festival in the French town of Herrison, five hours from Paris. They wanted him to perform the play in the original Urdu. Not knowing the language or the context, he expected people to walk out after the opening monologue. Any minute, he thought, the door would open and the viewers would trickle out. In the end, not only did no one leave the hall, but he also got a standing ovation. People came backstage to request if they could feel the brocades and the jewellery.

Much like his father’s, most of Mohammad’s productions are spectacle theatre, rooted in Indian heritage, many of them performed at iconic locations like the Golconda Fort and the Taramati Baradari in Hyderabad. A few though, are contemporary, like Spaces, about an artist struggling to preserve her identity; and the autobiographical Under An Oak Tree. In the play, written by his wife Noor, the oak tree symbolises his father. A line in it goes, “Even when the oak tree was gone, its presence remained, sometimes casting the warmth and shade and sometimes the darkness and despair of a shadow.” In a way, the pain of losing his father has dulled to the peace of knowing that in him, his father lives on.