Life in Sri Lanka’s capital city has not been easy in recent times. Kareema Datha, 25, a resident of Colombo, spends at least an hour a day in long queues outside supermarkets or grocery stores to buy essentials like milk powder, sugar, rice, vegetables and cooking oil. When she finally gets in, she is faced with empty aisles, in most of the shops.

Even when items are in stock, Kareema, a household help, can barely afford them. For example, the price of sugar jumped from LKR100 per kg in April to LKR230 per kg now (approximately Rs85). Similarly, the price of lentils went up by LKR40 per kg between April and August. “I was spending 750 rupees a week for my groceries and vegetables,” said Kareema over the phone. “It is now around 1,500 rupees, almost double.”

Hoarding was evidently identified as the issue and, on August 30, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa announced strict controls on the supply of essential goods. A statement issued by his office said that essential items would be purchased by the government and provided at fair prices. But, what seems to be the root cause of the inflation—the apparent scarcity—was not properly addressed. This is not surprising given that authorities seem to be asserting that there is no food shortage (see interview with Sri Lanka’s central bank governor).

There is an argument to be made for a direct link between the decline in the island country’s foreign exchange reserves and the empty aisles in shops—the ban on the import of chemical fertilisers. It was reportedly part of Sri Lanka’s effort to be more judicious with its forex reserves. Going forward, the ban is expected to cause serious problems for Sri Lanka’s tea industry. Plantation owners fear their crop could fail as early as October, without chemical fertilisers. This would have a severe economic impact on the three million labourers who pick leaves. In fact, central Sri Lanka—Kandy and the hilly country—rely completely on income from tea and rubber.

While the shortage of food and other essentials is more easily noticeable, experts said there are other signs of trouble, too. The central bank had recently put restrictions on banks, preventing them from declaring profits until accounts had been audited. Economists assert that this is indicative of a looming banking crisis.

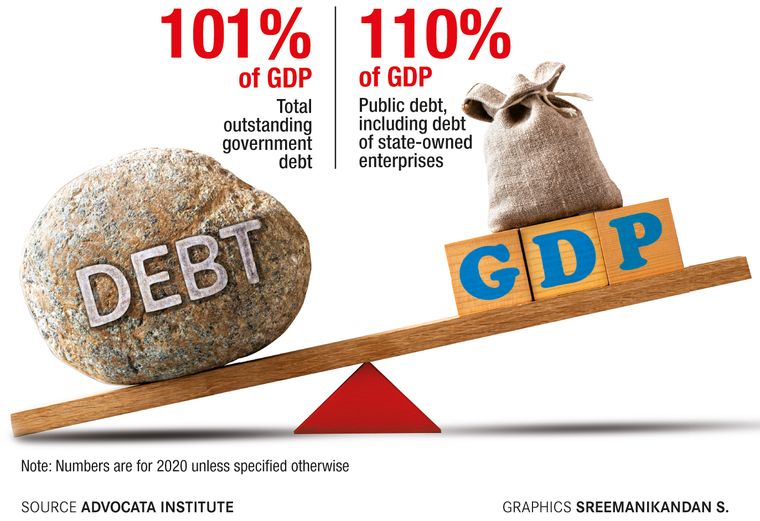

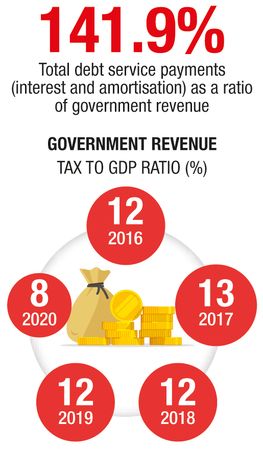

K.D.D.B. Vimanga, policy analyst at the Advocata Institute, a think-tank based in Colombo, said: “If reforms are brought in immediately at the macroeconomic level, the crisis will not worsen. It is high time we reform or perish.” He told THE WEEK that the economic crisis was caused by two factors—persistent fiscal deficit and external current account deficit.

Sri Lanka’s new finance minister, Basil Rajapaksa, had, on September 8, addressed the “severe foreign exchange crisis”. He informed parliament: “The data from the central bank shows the country’s net foreign exchange reserves are close to zero.” He added that the government’s revenue had fallen “between 1,500 and 1,600 billion rupees” from the estimate, because of Covid-19. “We are facing a severe external crisis as well as a domestic crisis with revenues falling and expenses continuing to rise,” he said.

After Covid-19 robbed Sri Lanka off its tourist dollars, its foreign exchange reserves dropped to $2.8 billion in July from over $7.5 billion in 2019. However, central bank authorities argue that the decline in forex reserves was because Sri Lanka settled debts to the tune of $2 billion in one year. After the debts were repaid, the import cover of the forex-strapped country fell to 1.8 months, against the usual minimum of three months. The value of Sri Lanka’s rupee against the dollar has also dropped steeply, depreciating by 8 per cent till September.

Ahilan Kadirgamar, senior lecturer in the department of sociology, University of Jaffna, said that the pandemic only compounded existing issues. “The economic crisis has been emerging for a number of years because of the kind neo-liberal policy that was carried out in Sri Lanka.” He said this was why Sri Lanka has extreme levels of external debt. He added that even before Covid-19 the government revenue had been declining. There were other issues, he said, such as imports being double the exports, and remittances declining.

“The macroeconomic issues the country faces have been brought about by poor fiscal management,” says Vimanga. “Successive governments have run large budget deficits which have been financed through borrowings both from domestic and foreign sources. This has, in turn, led to serious concerns on debt sustainability. Unless the root cause for the macroeconomic situation the country faces is not addressed, other measures such as import restrictions will only provide temporary relief and will in the medium- to long-term create other distortions in the economy.”

He added that while there has been an increasing reliance on Chinese loans to finance large infrastructure projects, the pertinent question was whether this infrastructure has led to an improvement in productivity.

The International Monetary Fund gave Sri Lanka special drawing rights of about $800 million in August to boost its forex reserves. And multiple currency swaps have been signed, including a $400 million deal with India. The deal makes sense from an Indian perspective. India’s relationship with Sri Lanka has soured in recent times and Indian exports have also reduced because of the recent restrictions. If the macroeconomic imbalances in Sri Lanka continue to be a major issue, Beijing is only likely to become increasingly influential. However, financial experts said the adequacy of Sri Lanka’s reserves would still be tenuous without additional means to boost reserves. There is a debt of about $5 billion due in 2022.

Economists said the only way out now for Sri Lanka is to prioritise macroeconomic stabilisation. “This would mean implementing hard reforms such as debt restructuring, revenue consolidation, public finance management and public sector reforms such as enhancing monetary policy effectiveness and exchange rate flexibility,” said Vimanga. “Improving the country’s external finances requires policies that are pro-exports. Continuing some of the current policies that have an anti-export bias will have a serious impact going forward.”

Kadirgamar said: “The government has to focus on the fundamentals like essential items, so that at least we don’t end up in famine.” He added that the agriculture policy—the ban on import of fertilisers—is not feasible. “It will result in a huge drop in production,” he said. “Sri Lanka is self-sufficient in rice cultivation, but there can be a drop in it, too, if this continues. The focus should be on agriculture, food, people and livelihood.”