After 16 years as German chancellor, Angela Merkel leaves behind a huge legacy. It bears her name, merkeln. The word captures the nuanced, complex and contradictory nature of her legacy. It is her. It is politics. It is life.

Merkel’s cautious, consensual, incremental decision-making is so distinctive, that it became a verb. Merkeln implies managing Germany’s evolution in a measured manner that reassured other countries and Germans themselves, calmly steadying the European Union in turbulent times. “This is her greatest legacy,” said foreign policy expert Daniel Hamilton. When she attended her 107th—and possibly last—EU summit in Brussels in October, European Council President Charles Michel called her a monument. “A summit meeting without you will be like Rome without the Vatican or Paris without the Eiffel Tower,” he said.

Merkel, the “girl” who grew up behind the Iron Curtain in impoverished East Germany, transformed into “Mutti”—the mother of the unified German fatherland. She took her conservative, right-wing Christian Democratic Union to the centre, expanded Germany’s political and economic power in Europe and became the EU’s biggest defender. Experts say her backing of the EU’s €800 billion pandemic recovery fund in May 2020 by allowing the bloc to raise common debt in capital markets for the first time—an option fiercely resisted by her party for decades—potentially prevented a disintegration of the union.

According to a Pew poll, the 67-year-old Merkel is the world’s most trusted leader. For 10 years, the Forbes magazine has ranked her the world’s most powerful woman. She is the longest serving head of state in the democratic world. Dismayed by their own leader, American commentators began calling her “the leader of the free world” during the Donald Trump presidency (a title that made her cringe as much as when a Barbie doll was named after her!)

Former US president Barack Obama told Merkel that the entire world owed her a debt of gratitude for taking the high ground for so many years. Merkel was the solid, sensible, ethical woman of gravitas who counterbalanced the testosterone and braggadocio of the mighty men of global politics like Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping. She tactfully and pragmatically balanced great power rivalries. Her fact-based, understated, unrhetorical style sharply contrasted with Trump who relentlessly baited the EU, Germany and her. Obama had urged her to run for a fourth term because of the risk to Europe from Trump.

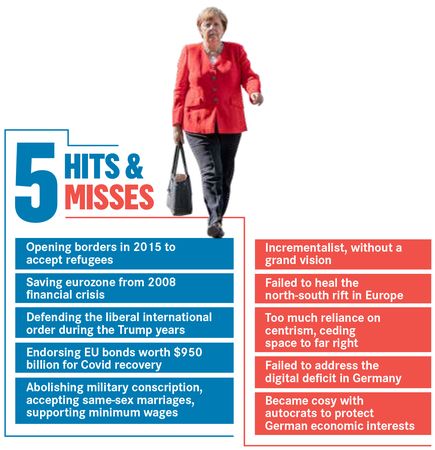

But sometimes Merkel seemed as immovable as the Eiffel tower. Merkeln also signifies “postponing decisions”, “dithering” or “failing to have an opinion,” reminiscent of the late Indian prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao who famously said that not making a decision was also a decision. Merkel refused to get sucked into breathless news cycles, patiently consulted opposing viewpoints and gauged public mood before deciding. Her legacy includes brokering countless compromises at EU, G7 and G20 summits, steering four coalition governments at home, and working with or outmanoeuvring authoritarian leaders, allies, coalition partners and party rivals.

“Merkel’s tenure is characterised by crises,” said political scientist Charlotte Galpin. Merkel weathered many crises, but they also left a trail of unintended consequences. The eurozone meltdown that followed the 2008 financial crisis was contained, Greek debt managed and Grexit prevented. But the austerity measures imposed had devastating unintended consequences—anti-Merkelism, with banners of her in Hitler moustache mushrooming and the rise of populism across Europe, kindled by public pain.

Russia is a frenemy. The Russian meddling in German elections, the hacking of the Bundestag (parliament) server and disinformation and propaganda operations on social media are major challenges. Merkel criticised the Russian annexation of Crimea and the attempted assassination of Russian dissident Alexei Navalny. She supported new sanctions against Russia. But despite strong US objections, Merkel pursued business with Russia, going ahead with the Nord Stream 2 project that will supply Russian gas directly to Germany, supplementing transit through Ukraine. Despite China's human rights record, Merkel pushed through a China-EU investment deal just before President Joe Biden took office.

These are cited as merkantilism, a word coined by political scientists Matthias Matthijs and Daniel Kelemen, signifying the “prioritising of German commercial and geoeconomic interests over human rights and democratic values”. But they can also be seen as pursuing national interests. Critics say she did not do enough to stop Brexit, but even they admit she persevered to prevent a no-deal exit. Germany initially did well during the pandemic, but poor infrastructure and decentralised processes led to chaos and over 70,000 deaths.

Merkel’s legacy of unintended consequences flowed even from noble decisions. Reacting to public fears after Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster, Merkel announced the phasing out of nuclear energy. But Germany’s dependence on coal increased, hiking carbon emissions and angering climate activists.

The worst unintended consequence stemmed from a crisis of her own making —welcoming one million refugees into Europe in 2015. The backlash was intense. Germans objected furiously, while populist rulers in Poland and Hungary made gains. But she stood her ground. Former Dutch prime minister Ruud Lubbers said it was a matter of deep moral conviction. But Hungarian President Viktor Orban called it “moral imperialism”. Critics saw merkantilism even in this decision—supplying workers to labour-starved German businesses. Merkel cut a shady €3 billion-deal with presidents and warlords to restrain the refugees in Turkey and Libya.

A consequential unintended consequence of the migrant crisis was the rise of the far right throughout Europe and especially, the Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) in Germany. This small Eurosceptic fringe group turned into a fiery, xenophobic party, roaring into national consciousness and into the parliament for the first time in 2017, becoming the main opposition. But the AfD has since weakened due to infighting and because migrants are no longer an inflammatory issue. It is now only the fifth biggest party in the German parliament. But it won in Thuringia and Saxony in former East Germany. The east-west divide in Germany is marked by disparity, with the east languishing behind the west in income and infrastructure. Deindustrialisation in the wake of globalisation has destroyed jobs.

This social and political discontent finds its outlet in the AfD, which endears itself in the region with its Molotov cocktail of racism, white supremacy, xenophobia and anti-immigration stances. Here, being called a Nazi is a badge of honour. The unapologetic lurch to extreme right consolidates the AfD’s core base, but it makes it lose votes nationally, provokes other political parties to treat it like a pariah and encourages German domestic intelligence agencies to keep it under surveillance.

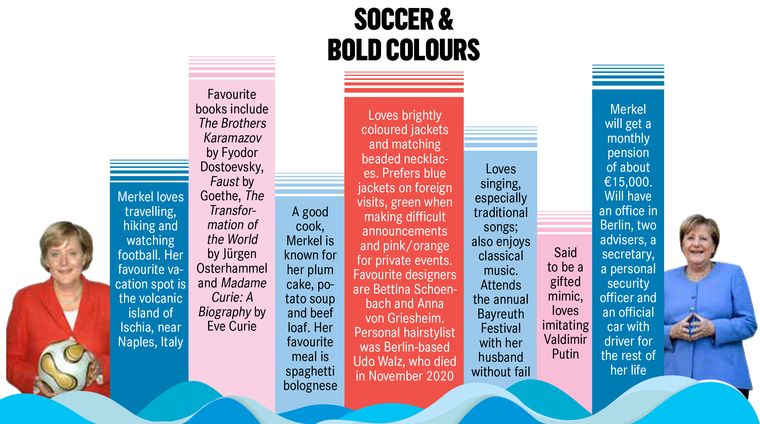

In 2018, Merkel announced she would not seek a fifth term, exiting at a time of her choosing. Her predecessors mostly lost elections or were ousted by scandals. She has been the very antithesis of the heavy-smoking, hard-drinking, womanising, wheeling-and-dealing, domineering big men of West German politics. Merkel is the first woman chancellor, the youngest and the first from East Germany. If government-formation talks drag on past December 17, she will overtake her mentor Helmut Kohl to become the longest-serving chancellor in modern German history.

Merkel will enter the pantheon of the great German chancellors who shaped the course of their nation’s history—Konrad Adenauer who brought a democratic Germany into NATO and reconciled with Israel and France, Ludwig Erhard who stewarded Germany’s economic miracle, Willy Brandt who sought détente with the Soviet Union and asked forgiveness for holocaust by falling to his knees in a Warsaw ghetto and Kohl who steered the reunification of East and West Germany.

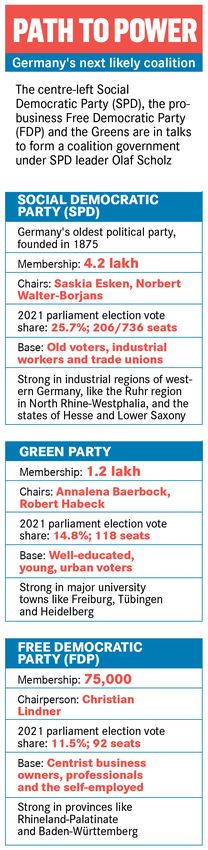

Pollsters say had Merkel contested, she would have won a fifth term. Instead, candidates jostled to be her heir. Her own party's candidate lost and the next likely chancellor is social democrat Olaf Scholz, who stakes claim to her mantle as he was her finance minister in the outgoing coalition government. A new centre-left “traffic light” coalition–named after party colours of Social Democrats, Free Democrats and Greens—is expected to form the next government. It promises no tax increases, balanced budgets, exiting from coal by 2038 and increasing the minimum hourly wage to €12.

Throughout her political life, Merkel towered over the sleaze and scum of everyday politics. She remained a private citizen of impeccable integrity, dedication and intelligence, living in her own modest Berlin apartment as chancellor, shopping for her own groceries. Her outstanding quality is her normalcy. She consistently wore black pants, uni-colour hip length jackets and flat shoes. Historian Jan-Werner Müller said Merkel’s anti-charisma had turned into a kind of charisma that communicated sincerity. Her anti-oratorical speaking style anaesthetised listeners and she demobilised opponents by dulling and depoliticising conflicts. An aspect of merkeln is being so self-restrained that it is hard to pin her down.

To understand Merkel, perhaps one must travel to her past. “I know what living in a collapsing system feels like and I don’t want to go through that again,” she told her biographer Stefan Kornelius. Daughter of a pastor, Merkel is the good girl from communist East Germany who rose by excelling in school, speaking little and trusting few. She kept her first husband’s name and married Joachim Sauer, a quantum chemist, like her. Her scientific training frames her worldview—a level-headed empiricist who is unimpressed by grand visions, histrionics and hyperbole.

Merkel is a celebrated “incrementalist’, taking small-step decisions, not huge leaps to solve complex problems, muddling, adapting, compromising, recognising both possibilities and limitations. It is too early to judge her legacy because future events also determine legacies. If the EU falls apart, people will glorify the Merkel days. If it becomes stronger, she will be remembered as the stepping-stone.

Merkel has declined offers to chair various organisations. When she goes, she goes… literally into the wilderness, hiking on mountain trails with her husband, reading, travelling and watching football. She would “simply enjoy some leisure time knowing that no possible upheaval may happen in the next 20 minutes… a little melancholy will perhaps also come later,” said Merkel. When asked what she looked forward to most in retirement, she replied, “Not having to constantly make decisions.”