Creme diplomat is the hottest item on New Delhi’s summer menu. With the easing of Covid-19 restrictions and a world order on the churn, diplomats from across the world, and more significantly, from across various camps, have been heading towards India, keeping officials of the ministry of external affairs, who had got used to virtual meets, on their toes.

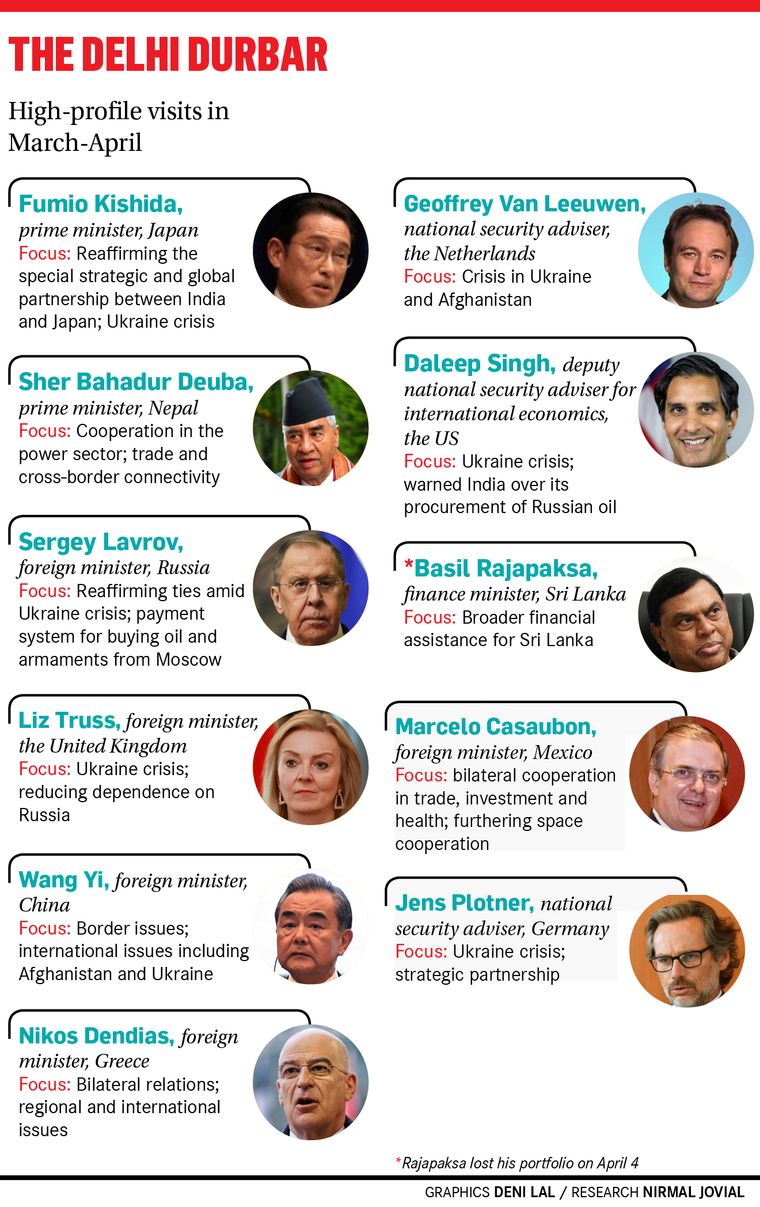

Over the last few days, India has hosted two heads of government (Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Nepalese Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba), five foreign ministers (Russia’s Sergey Lavrov, UK’s Liz Truss, China’s Wang Yi, Greece’s Nikos Dendias and Mexico’s Marcelo Casaubon), two national security advisers (Germany’s Jens Plotner and the Dutch Geoffery Van Leeuwen), and a deputy NSA, Daleep Singh from the US. Israel’s Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s visit was cancelled because he got Covid; his defence minister’s visit, too, was rescheduled because of security incidents in Israel.

India also held two important trade meets with the UAE and Australia virtually, the former taking forward a landmark trade pact and the latter inking the Economic Cooperation Trade Agreement (ECTA). The phone lines are busy, as key officials of various countries reach out to their Indian counterparts. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called up External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar a day before Lavrov’s visit. Meanwhile, the French navy engaged with the Indian Navy in the Varuna exercise in the Arabian Sea.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is the number one agenda at most of these interactions, either directly or indirectly. Only Nepal’s Deuba focussed almost exclusively on bilateral relations.

At the India-Japan summit, Kishida mentioned Ukraine, while India kept away from the subject. India and Japan are partners in many economic projects, including development in the northeast, the bullet train and smart city projects. The Japanese side told media persons that Ukraine dominated the conversation for nearly 95 of the 110 minutes that the two prime ministers were together.

Japan used diplomatic language to tell India to switch over from the Russian side to the US-led one. Truss and Singh used firmer language. Truss, while noting that she would not tell India what to do, kept the emphasis of her remarks on the Russian aggression, helping Ukraine and how the UK planned to reduce its energy dependence on Russia. She conveyed the “importance of democracies working closer together to deter aggressors, reduce vulnerability to coercion and strengthen global security”.

Singh was blunter in telling India that the next time China invaded India, Russia would not come to India’s aid. India largely ignored Singh’s comment, but Truss found herself in an embarrassing face-off with Jaishankar at an event, where he actually called out the west on its duplicity, noting how their energy imports from Russia actually increased in March, even as they went blue in the face talking about sanctions. Truss saved face by saying that strengthening the relationship with India had become more important than it has ever been precisely because we are living in a more insecure world.

Truss’s visit coincided with Lavrov’s and the difference in their receptions was telling. While she was received as per standard protocol, he had a meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In fact, Lavrov is the only visiting dignitary (apart from the government heads, Kishida and Deuba) with whom Modi held a meeting.

US President Joe Biden recently commented that India’s position [on the conflict] has been “shaky”. However, Jaishankar had earlier told Parliament that India’s position was “steadfast and consistent”, calling for an urgent cessation of violence and noting that dialogue and diplomacy was the way forward.

While at the various fora of the United Nations, India has shown its neutrality, by abstaining on a number of resolutions on the conflict, it has not buckled to any pressure to join the sanctions against Russia, which has offered oil to India at discounted rates, even assuring last mile security for the import. Jaishankar noted that India’s traditional suppliers are the Middle East, but if the west has issues, why has it upped imports of Russian oil?

Pictures are telling. Jaishankar and Truss shake hands literally at an arm’s length from each other, Lavrov and Jaishankar’s handshake is closer and firmer. Images of Modi and Lavrov are even more congenial. And Wang Yi and Jaishankar’s picture together is the most telling, they do not even shake hands, preferring to fold their hands in a namaste pose.

The west is finding India’s friendship with Russia very testing, and is fast losing patience. It cannot speak down to India like it can to some other nations, or use threats like withholding aid. In another era, perhaps it could have been more directly critical of India’s independent foreign policy. In these times, however, the situation is complex. Before Russia’s actions, America’s rival—and threat—number one was China. Economically, it still is. America’s new thrust in foreign policy—renaming Asia Pacific and Indo Pacific, and wooing India into the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—is with an eye on China. Directly alienating India, therefore, comes with complications it would rather do without.

India’s position, incidentally, is not too different from most Asian nations, except American allies Japan and South Korea. The Middle East countries have refused to lower their oil prices to unsettle Russia. And all would rather not get roped into someone else’s war. Israel, while siding with the US on facilitating execution of the sanctions, and voting on the US side at UN resolutions, too, has deep ties with Russia that it does not want to jeopardise. As Jaishankar noted, the situation in Afghanistan impacted the region directly, Ukraine has not.

Among the Quad nations, Australia so far has shown the most understanding and patience with India’s position. Could that be because the free trade agreement was in the last stages of being put together? The two nations signed the Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) on April 2, a huge development in the bilateral relation. A ministry official said it was on the lines of the one India signed with the UAE some years ago.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said, “This agreement opens a big door into the world’s fastest growing major economy .... by unlocking a huge market of around 1.4 billion consumers in India, we are strengthening the economy and growing jobs right here at home.” Clearly, national interest is foremost. The deal was inked a day after Lavrov’s visit.

Earlier in March, a UK cross-party 10 member delegation’s scheduled visit to India was cancelled without either side giving a reason. Observers on both side attributed it to differences over Ukraine. Post Brexit, the UK is forging a trade pact with India; the third level of talks is scheduled this month. It is reported that UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson might visit India this month. Truss has taken back a measure of India’s attitude.

While India’s present position is not too different from its traditional one in international conflicts (it abstained from the US-led UNSC vote in 2011 on a no fly zone over Libya), the difference this time is India’s firm assertion of its position. It is guided by its security and national interests, no doubt, and that is what the official line is. However, this is also payback time for the many occasions when Russia had India’s back.

The US factored in India’s closeness to Russia when it reached out with new military pacts and other deals of friendship. It knew it could only push India so much, and not more on certain issues. Russia remained tolerant when India forged a new friendship with the US, and though disapproving of the Indo Pacific, it maintained that it understood India’s position on the topic.

Lavrov, while in Delhi during the Raisina Dialogue in 2019, lashed out at the “exclusivity” of the Indo Pacific concept, and said the onus was on India to convince Russia otherwise. The ongoing conflict is the moment when India has proven that in action, refusing to isolate Russia diplomatically.

It was only a year ago that India reeled under the massive Delta wave crisis and Modi reached out to the world for help. Russia was among the first to send relief material including 20 oxygen producing units, largely without overt publicity. UK, France and Germany were quick to respond, too. America’s knee-jerk reaction, however, was to hold onto its cache of raw material for vaccines, a move that drew criticism from its own officials. Though the US sent oodles of air and aid in the days and weeks that followed, Biden’s initial dithering will always be remembered.

China, meanwhile, finds itself on the Russian camp more by default than design. While India may choose to ignore Singh’s comment, deep down, the Russia-China closeness is being closely watched. China and Russia share a longer border, the two nations are part of many groupings, in many of which India is also present—Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), BRICS and the Russia-China-India group.

Wang’s visit across South Asia recently was to reassess ties in this part of the world, which is in its own flux, thanks to the Afghanistan situation. This being the year of China’s presidency of BRICS, he is also laying the ground for a probable Modi visit, in case the summit is physical. India, however, made it clear that it is not business as usual with China as long as the border situation remains unresolved.

Across the world, nations are finding different ways to deal with an assertive India, and woo it to their side. So far, India has managed this delicate diplomatic dance with its posture firm and head high. As the manoeuvres get more complicated, will India be able to choreograph its way through with the same elan?