The Bidens are known for their carefully planned state dinners. South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s dinner in April was a homage to the 70-year-long bilateral relationship. It was marked by references to the special nature of the bond. Cherry blossoms adorned every table, Korean American celebrity chef Edward Lee was roped in to curate the menu, which was finalised after ten rounds of tasting. Yoon’s favourite song from his childhood, “American Pie”, was performed. In a surprise move, the South Korean president crooned the Don McLean song himself. But come June 22, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi attends his state dinner, the Bidens are expected to top all that.

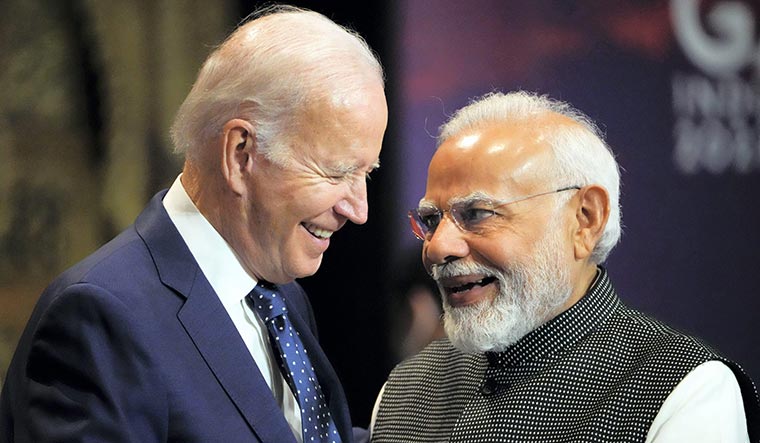

“From my husband, I learned that all politics is personal,” said First Lady Jill Biden at a preview of the Yoon state dinner. It has never been truer for India and the US than it is now. Modi has thrown his weight behind making the bilateral relationship stronger than ever. And Biden has shown that he, too, is clearly committed.

The deal to jointly produce the GE F414 jet engine in India is likely to be finalised during the visit. Throw in the complete technology transfer, and the package looks complete, as the Americans are fiercely protective of their technology. “It is a visit where the emphasis is on strategy,’’ said foreign affairs expert Rakesh Sood. During Donald Trump’s time, the focus was on much thornier aspects like visa and trade―which are still unresolved―but this time, the key takeaways will be technology and strategy. Driven by the prime minister’s office, rather than the defence ministry, defence cooperation is on top of the agenda. Biden’s National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan landed in Delhi on June 13 to work out the details under the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET), signalling the importance with which both governments are looking at enhancing defence ties. It will be useful as trade negotiations have not progressed much.

The Biden administration is believed to have intervened to ensure that India gets access to the jet engine technology, giving Atmanirbhar Bharat the boost it needs. Just ahead of Modi’s visit, the White House offered more: National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby called India a vibrant democracy, responding to a question on the issue. “Anybody who happens to go to New Delhi can see that for themselves,” he said. The statement was significant because in February a report by the senate foreign relations committee had commented on the “downward trend of democratic values and institutions” in India. A month later, a state department report said there were significant human rights issues in India. Kirby’s certification was, therefore, essential, as it assures Americans that India remains a member of the global democratic alliance. It was also a message that Biden had Modi’s back.

Framing a message: Prime Minister Modi with Ukrainian President Zelensky on the sidelines of the G7 summit in Hiroshima | Getty Images

Framing a message: Prime Minister Modi with Ukrainian President Zelensky on the sidelines of the G7 summit in Hiroshima | Getty Images

The state visit, however, goes beyond boosting Modi’s image even as he becomes the only Indian leader to address the joint session of the US Congress twice. With a combative China and a ‘rogue’ Russia posing a major threat to the liberal, democratic world order, the visit will certainly be viewed through both these prisms. For the US, it is essential that India plays along on both issues so that it can achieve its Indo-Pacific goals, especially reiterating the primacy of the democratic order. It also wants to convince the Global South, where India holds sway, that sitting on the fence on Russia is not a choice.

Does that mean that Delhi has chosen to ignore Moscow? There are signals of a slight recalibration. The Ukraine war has dragged on for more than a year. India has not condemned Russia. But in the past three months, there seems to be a little more empathy towards Ukraine, especially after the visit of Deputy Foreign Minister Emine Dzhaparova. India, however, reportedly rebuffed her attempts to get President Volodymyr Zelensky invited to the G20 summit in September. “It is only for members. We have not reviewed the list, nor has anyone talked to us about it,” said External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar.

Modi, however, met Zelensky on the sidelines of the G7 summit last month in Hiroshima. Their picture together spoke a thousand words. India is aware of how sensitive Russia would be and how the move would be interpreted by Moscow. There are other signs, too. The 22nd heads of state summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to be held in Delhi, where Vladimir Putin was expected to be present, is now being held virtually.

In Russia, there is growing concern over India’s relationship with the west. “India is indulging multiple partners,’’ said Nandan Unnikrishnan, distinguished fellow at Observer Research Foundation. “There is a knock on the door. Earlier, the Russians were confident that India would not answer, but now they fear that India may be tempted.” The jet engine deal may not immediately shift India away from Russia, but it could create an ecosystem where Russia ceases to matter.

For the Russians, the worry is real. If the joint production of the F414 engines is not sweet enough, the Germans are courting India with a deal for submarines. Earlier this month, US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius were in Delhi. Pistorius was hoping to clinch a deal for six submarines. “India is trying very hard to reduce its dependency on Russia,’’ said Pistorius.

What these developments mean for the cooperation India has with Russia―like the S-400 missile system deal―remains to be seen. These are difficult conversations that New Delhi will certainly have with Washington.

What has also helped India inch closer to the US has been the deliverables on terrorism. The labelling of Jaish-e-Mohammed founder Masood Azhar as an international terrorist was one such mission, and the ongoing battle to get Tahawwur Rana extradited is another one.

Moreover, India’s discourse around terrorism has changed, especially in the context of Pakistan. “With Balakot, India has shown that it can respond,’’ said strategic affairs expert Harsh Pant. “But terrorism is global in nature and institutional mechanisms to deal with it―be it the Financial Action Task Force or the United Nations―need to act. Also, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan has, in a way, reduced its reliance on the Pakistan army.”

While India will be ready to cooperate with the US to form an economic shield against China’s Belt and Road Initiative, it will not be an ally like Australia, Japan and the UK. “India is likely to avoid military participation in coalition operations that may be necessary against China in a contingency, like a war in Taiwan,” said Ashley Tellis, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, at a recent webinar. “No matter how deep our partnership gets, there are some thresholds that India is unlikely to cross.’’

Meanwhile, the China question is changing for the United States as well. Washington had requested a meeting between defence chiefs of both countries on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore held earlier this month, but China declined. However, Secretary of State Antony Blinken is expected to travel to Beijing on June 18. The thaw that Biden predicted at the G7 summit may finally come to pass.

“The Americans could try and create some distance between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping,’’ said Sood. India will be happy as it is uncomfortable about the growing Sino-Russian ties. On the other hand, it will have its concerns about a Sino-American reconciliation. As Sood says, “A multipolar world is promiscuous by nature.”